A Week of Elections from A to Z

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

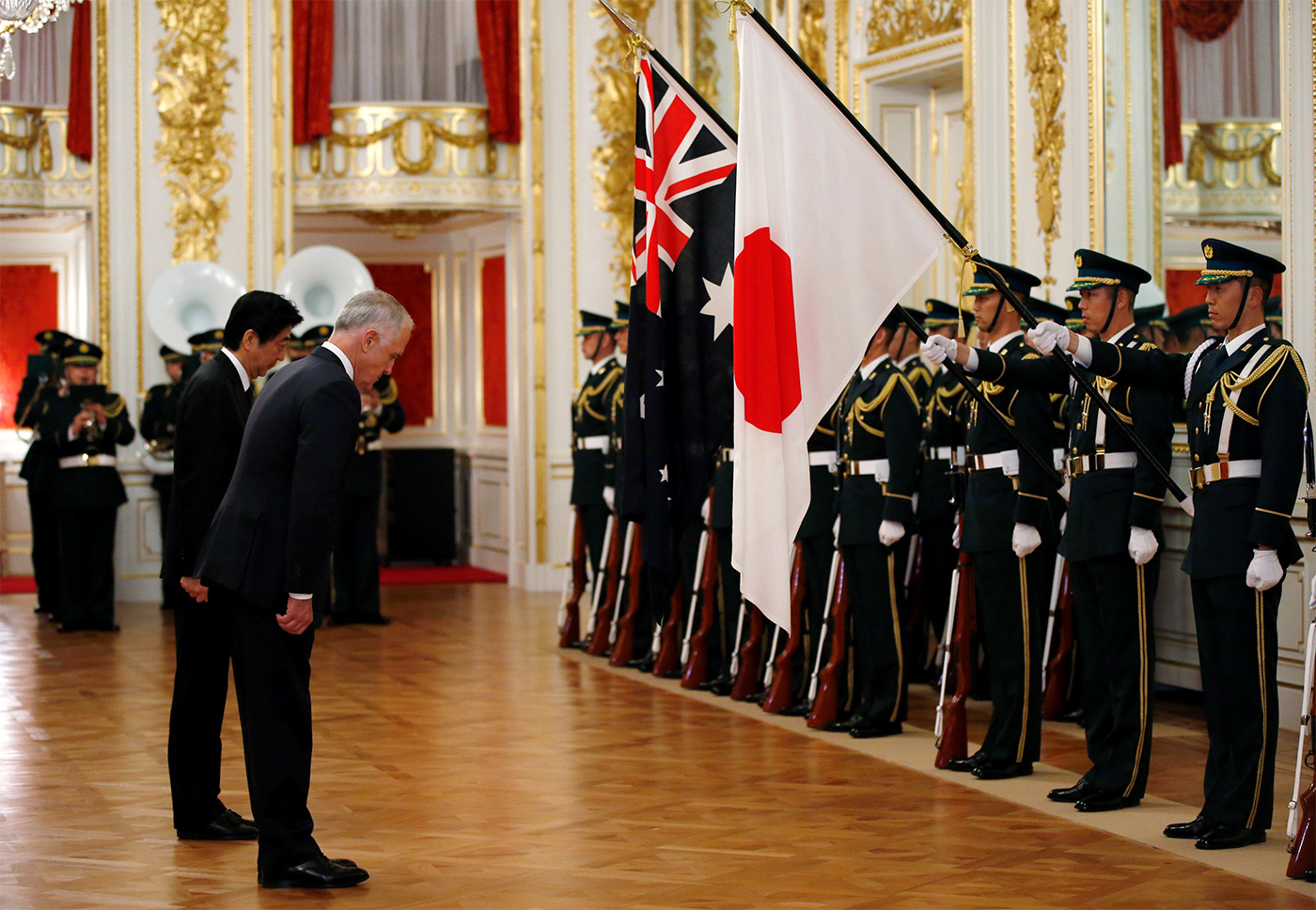

Two parliamentary monarchies in the Asia-Pacific (and bosom buddies) – Australia and Japan – held parliamentary elections at the same time. For the first time in 30 years, on July 1, the Australian people voted for candidates to both chambers of parliament after the leader of the ruling Liberal–National coalition, Malcolm Turnbull, called a general election to secure a long-term mandate for reform. Australia is at a crossroads, as it has to adapt to a decline in commodity prices and an economic slowdown in China, its key trading partner.

Shinzo Abe, Japan’s Prime Minister led the ruling Liberal Democratic Party in the elections to the upper chamber of the National Diet under somewhat similar circumstances – he needs support for economic and constitutional reforms – but with a lower risk for his own positions. The bottom line is that Malcolm Turnbull’s victory barely escaped turning into a pyrrhic one, while Shinzo Abe effectively got yet another confirmation of his mandate.

REUTERS/Toru Hanai

In addition to geopolitics and mutually complementary economies, the alliance between Australia and Japan is rooted in their similar political systems and shared values. The relationship started to strengthen particularly during Shinzo Abe’s first term (2007–2008). The day after returning to power in December 2012, the Prime Minister of Japan published a programme article touting the idea of a “Democratic Security Diamond” – a four-way partnership between Australia, India (the world’s largest democracy), the United States and Japan.

Like Australia, in recent decades Japan has experienced structural problems in domestic politics – a “revolving door” of government leaders. In Japan, the phenomenon took place in the period starting from the late 1980s, with a two-and-a-half-year break for Ryutaro Hashimoto and a five-year respite for Junichiro Koizumi (2001–2006) as well as clouding Shinzo Abe’s own first term (2006–2007). Or, maybe the opposite – perhaps it preparing him for a long haul: Abe’s second term has already become the fifth longest in the post-war period and is likely to end up the fourth longest given the fact that his diligence is projected to let him stay in power until 2018.

In Australia, the cabinet doors started revolving at the end of the 2000s, as the leadership spill in both parties intensified. Battles within the party propelled the current Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, to power in 2015 to replace Tony Abbott. Yet the dissolution of parliament came back to haunt Mr. Turnbull, as on July 1, he prevailed by a tiny margin only, having weakened the advantage that the ruling coalition used to have over its Labor opposition. The epic vote counting has been dragging on for over a week now, and a final result will show whether Mr. Turnbull needs a helping hand from independents, or if his Liberal–National coalition can form a government by itself. While Labor leader Bill Shorten conceded defeat, he was quick to take inspiration from his newly bolstered positions to predict a return to the poll in less than a year.

REUTERS/David Gray

In contrast to Australia, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party–Komeito coalition in Japan has increased its representation in the House of Councillors. As a result, taking the independent candidates from assorted small parties into account, both chambers of the National Diet now have a two-thirds majority to support amendments to the country’s constitution, which is deemed pacifist because of its restrictions on armed forces. Shinzo Abe has already indicated his eagerness to accelerate public discussions of this matter, but Komeito leader Natsuo Yamaguchi has stated that he does not expect progress to be made on the issue.

REUTERS/Toru Hanai

And finally, we can offer some speculation on an election of a different type – in the domain of foreign policy and defence. It’s possible that Tokyo was privately gloating over Mr. Turnbull’s sudden problems, as his predecessor, Tony Abbott, had given Shinzo Abe reason to hope that Japan would get to build eight submarines for Australia costing a total of $38 billion. The Japanese side believed that it was a done deal at the time, as the leaders of the two countries had a trusting relationship, and viewed the tender procedure subsequently initiated by Australia’s defence officials as a mere formality. Yet under Mr. Turnbull, considered to be more dovish towards Beijing, the tender turned out to be not a fixed match but a real competition, with Germany and France joining the fray. What is more, even though the Japanese side had long been promised a win in the tender, the contract eventually went to France, with their technology still being at the design stages, unlike Japan’s tested Soryu-class submarines.

Japan’s experts have described the situation this way: a young Australian fellow first asked for the hand of a simple Japanese village girl who trusted him, but eventually succumbed to the charms of an experienced French woman. Whatever the metaphors, even if Malcolm Turnbull had lost the election, the submarine contract would have sailed to France anyway, while pacta sunt servanda. It remains to be seen what conclusions Shinzo Abe’s foreign policy team, which cultivates both pragmatism in personal relations of trust between the Japanese leader and his foreign peers and the shared value-based partnership in Asia-Pacific, will draw out of all this.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |