Russian President Vladimir Putin’s visit to North Korea, or the DPRK, which has been under discussion since January 2024, could not only be perceived as a reciprocal visit after the North Korean leader’s visit to the Russian Far East in the fall of 2023 but also as an extremely important step in bolstering relations between Moscow and Pyongyang.

Russia’s withdrawal from the sanction regime seems logical, but Moscow is now seriously weighing the risks. On one side of the scale is the benefit of expanding cooperation with the DPRK, as many of its areas are currently blocked by sanctions. On the other is restrictions through the UN, since a situation when a permanent member of the Security Council, which voted in favor of sanctions, openly violates the relevant resolution, will clearly become a reason for a new round of pressure. The arguments that Russia as an aggressor should be expelled from the UN or deprived of its veto power periodically leak into the public domain, and these will have to be reckoned with. That is why Russia’s position currently boils down to the fact that it is against new sanctions, but intends to comply with the old ones, although proceeding from the principle of “what is not forbidden is allowed.”

Therefore, when speaking about further expansion of cooperation between the two nations, it is necessary to divide this cooperation into several levels of involvement, the depth of each to depend on a whole set of factors. First of all, the level of confrontation between Russia and the Collective West, the regional situation in Northeast Asia and on the Korean Peninsula, and, to a much lesser extent, on the military and political situation on Russia’s borders. It is not quite likely that Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong-un sign a number of documents “on the transition to the next level” straight off. Rather, this will be a matter of developing a road map, where a system of cooperation will be worked out in advance, depending on the further development of the situation, with preliminary preparations being made first.

Anyway, when Vladimir Putin’s visit to North Korea takes place, this will be a landmark demonstration of the new level of relations between the two nations and Moscow’s diplomatic support for Pyongyang. Specific agreements may well be classified as secret, which is why “Scheherazade stops the allowed speeches,” preferring to deal with the analysis of events that have already taken place.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s visit to North Korea, or the DPRK, which has been under discussion since January 2024, could not only be perceived as a reciprocal visit after the North Korean leader’s visit to the Russian Far East in the fall of 2023 but also as an extremely important step in bolstering relations between Moscow and Pyongyang.

Vladimir Putin visited North Korea in 2020, and along with the inter-Korean summit between Kim Dae-jung and Kim Jong-il in 2000, this was a landmark event that allowed the DPRK to overcome its foreign policy isolation and Russia to embark on its “pivot to the East.” One could say that the Russian president’s visit to a country, which the Collective West had brandished as a “pariah” state, was a demonstration of Moscow’s reluctance to join the collective condemnation of the Pyongyang regime.

Russian-North Korean relations have seen both ups and downs due to Russia’s view on the DPRK’s aspiration to join the nuclear club. On the one hand, Moscow understands Pyongyang’s position, but on the other hand, it does not accept it because it would destroy the existing world order built on the authority of the UN and non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. Moscow has rather tried to play by the established international rules, and although Russian and U.S. diplomats could argue at length about the extent of sanctions following another nuclear test or missile launch, the idea that every step by the DPRK toward becoming a nuclear power would generate opposition was never questioned.

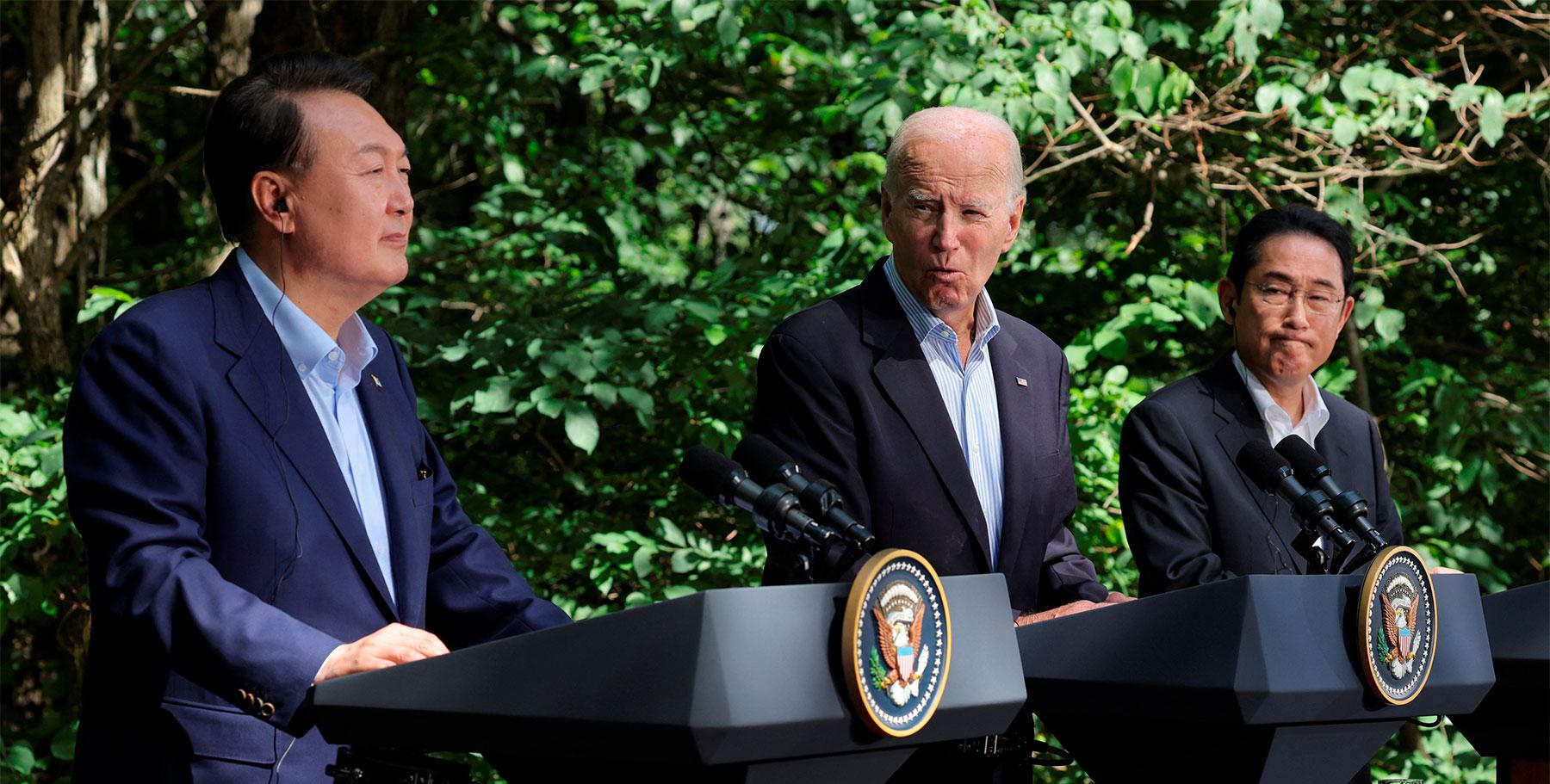

However, since the late 2000s and even more so since the early 2010s, the world has been moving towards a new model of the world order, or rather, it has been a gradual transformation of the old one. The confrontation between the “Collective West” and the “Global South” intensified; the UN and other structures began to turn into a system of justifying double standards, losing the role of an impartial arbiter; and war began making its comeback to politics. In this precarious environment, we see the malfunction of the accepted mechanisms and, although the contours of the new world order have not yet been defined, many elements of the traditional structure of global security are losing their significance. The common political, economic and information space is giving way to the era of blocs, which, due to the competition in the Russia-China-U.S. triangle, inevitably affect Northeast Asia and the Korean Peninsula. In the meantime, the “Asian NATO,” which was being formed after the trilateral summit in Camp David, seeks to justify its existence by a hypothetical alliance between Moscow and Pyongyang or Pyongyang and Beijing, positioned as an alliance of authoritarian regimes threatening democracy and democratic values. Meanwhile, this cooperation is unproven, to put it mildly, and it is based on innuendos or facts that at best (highly likely) can be regarded as circumstantial rather than direct evidence.

Note that the intensification of speculations about some secret arms deals between Moscow and Pyongyang did not begin on the eve of Kim Jong-un’s visit to Russia. This narrative has been on since June-August 2023, against the backdrop of the apparent failure of the Ukrainian counteroffensive, which had suffocated from a shortage of ammunition, among other reasons. This is why the campaign could be viewed as putting pressure on Seoul to reconsider its policy on the supply of ammunition and lethal weapons to Ukraine.

In this context, one of the options for further unfolding of events is the so-called “self-fulfilling prophecy” coming true, when cooperation between Moscow and Pyongyang may become a response to the actions of their adversaries within the framework of the “security dilemma.” North Korean statements in late 2023 and early 2024 about a radical change in inter-Korean policy and rejection of the unification paradigm caused a stir in expert circles and were even positioned as preparations for a forceful solution to the inter-Korean problem, even though it was more like a model of “non-peaceful coexistence” – something similar to the Soviet-American confrontation in the Cold War era. Meanwhile, South Korean President Yun Seok-yol’s speech in honor of the March First Movement for Independence in 2024, where he actually declared that the liberation of Korea would be fully accomplished only after the elimination of the DPRK, which should take place with the help of the international community, went virtually unnoticed, although in terms of inflaming regional tensions this was a much more serious step.

As a result, a more substantial revision of Moscow’s policy toward Pyongyang is expected from the Russian president’s visit to North Korea. The most radical forecasts concern the legitimization of military or military-technological cooperation and, more importantly, Russia’s withdrawal from the regime of international sanctions against the DPRK. As preliminary steps in this direction, Western experts refer to Russia’s position in the UN Security Council, where it first blocked the attempts of the United States and its satellites to further increase sanctions pressure on Pyongyang, and then, using its veto, paralyzed the official group of experts that formally monitored the sanctions regime and its violations that, in fact, proved to be nothing else than another instrument of pressure and name-calling.

In this context, Russia’s withdrawal from the sanction regime seems logical, but Moscow is now seriously weighing the risks. On one side of the scale is the benefit of expanding cooperation with the DPRK, as many of its areas are currently blocked by sanctions. On the other is restrictions through the UN, since a situation when a permanent member of the Security Council, which voted in favor of sanctions, openly violates the relevant resolution, will clearly become a reason for a new round of pressure. The arguments that Russia as an aggressor should be expelled from the UN or deprived of its veto power periodically leak into the public domain, and these will have to be reckoned with. That is why Russia’s position currently boils down to the fact that it is against new sanctions, but intends to comply with the old ones, although proceeding from the principle of “what is not forbidden is allowed.”

Therefore, when speaking about further expansion of cooperation between the two nations, it is necessary to divide this cooperation into several levels of involvement, the depth of each to depend on a whole set of factors. First of all, the level of confrontation between Russia and the Collective West, the regional situation in Northeast Asia and on the Korean Peninsula, and, to a much lesser extent, on the military and political situation on Russia’s borders. It is not quite likely that Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong-un sign a number of documents “on the transition to the next level” straight off. Rather, this will be a matter of developing a road map, where a system of cooperation will be worked out in advance, depending on the further development of the situation, with preliminary preparations being made first.

The first level of cooperation involves advances in existing areas for collaboration – their intensification is already clearly visible from the increased contacts between the two states in certain areas. First of all, this is the search for ways of economic cooperation that would not violate sanctions or exploit the “gray zones,” at best, to avoid direct accusations. Such work is carried out, including through an intergovernmental commission. The intensification of economic ties, which Western experts pass off as the consequences of the “arms deal,” indirectly proves this, since we are talking about the movement of ships with unknown cargo on board.

Second, it is the further development of transportation and communication infrastructure: we can expect not only the construction of a cross-border road bridge and the emergence of a regular railroad service, but also the arrival of Russian cellular communications in the DPRK or the connection of certain segments of the DPRK to the Russian Internet. It is not a question of replacing the existing intranet with something more, but those who have the right or ability to go online will do better. At the same time, cooperation of hacker groups or the training of North Korean specialists in such things will not be possible at the current level of cooperation, but only at the next level, where both countries will be galvanized by a common threat.

Third, there are prospects for cooperation in technology. Yet, so far, we’ve been talking not so much about transferring offensive military technologies to the North, but rather about North Korean satellites being launched on Russian carrier rockets, for example, or Russian computing power helping calculate the processes by which a nuclear test will be dictated only by political rather than technological necessity.

Fourth, there are prospects for cooperation in tourism, which does not fall under sanctions, given that the DPRK has been investing in attempts to create appropriate infrastructure organized according to European standards. The first group of tourists has already started visiting the DPRK, and if the “first pancake” is not a blob, more tourists will flock to the DPRK from Russia than even from China, as the Chinese have not been visiting Pyongyang too eagerly, despite the fact that the tourist cluster in Wonsan and the modernized cluster in the Kumgang Mountains were originally intended for them.

Finally, cooperation in education, healthcare, sports, and culture is very important. Contacts at the level of ministers or their deputies are the clearest sign of diplomatic activity intensification in the spring of 2024. In the future, it may even be a question of saturating North Korean medical centers with Russian equipment or opening a branch of a Russian hospital in Pyongyang with Russian medical staff and modern equipment, designed not only for Russians or other foreigners, but also for the local population.

The next level of engagement implies that Moscow and Pyongyang may enter into covert cooperation that violates the sanctions regime but does not directly disregard the UN resolution. Here, it is primarily a matter of using North Korean labor, which has earned a good reputation for its combination of value for money, the lack of criminal inclinations, and relative invisibility not only in Russia’s Far East. Some Russian officials have already announced their desire to import North Korean construction workers, so some Western experts have already accused the countries of organizing such cooperation under the guise of importing students, for example, who, according to Russian law, have the right to work part-time.

Other potential areas of cooperation include increased supplies of energy or prohibited dual-use goods that would nevertheless be used for peaceful purposes. In essence, everything that the Western media and biased experts have long accused Moscow and Pyongyang of doing would finally become a reality at this stage.

The next level of engagement implies that Russia may bluntly despise the sanctions regime in favor of a full-scale cooperation with the North, including in the military-technical domain. In particular, North Korean construction workers may openly travel to Russia’s Far East under this arrangement. As for military-technical cooperation, Russian carriers will then start launching satellites for dual or military purposes, plus Moscow may start transferring something useful to Pyongyang – more likely elements of technology rather than military equipment. In the extreme case, we could talk about single samples as prototypes for subsequent localization. The same may apply to the transfer of North Korean technologies to Russia, not so much as direct supplies of weapons or armaments, but rather as the creation of opportunities for screwdriver assembly or other options of creating equipment clones.

Theoretically, it is possible that the DPRK, while rearming its military units and switching from old to new equipment – for example, from 152 mm caliber to 155 mm caliber – will be dropping “obsolete ammunition” to Russia. However, such options look highly unlikely, because the possibility of an inter-Korean conflict is not going anywhere, and the experience of the North Korean Defense Forces shows how quickly peacetime ammunition stocks are depleted in the event of their use by the standards of a full-scale military conflict rather than a local skirmish.

The final level of cooperation, where all restrictions are lifted, can only be possible in case of extreme necessity, as the author believes, because it is associated with too high a level of associated risks. Thus, despite the fact that some representatives of Russia’s patriotic camp would like to take literally the statement that “Russia and the DPRK are in the same trench,” any option of internationalization of the conflict on the Russian side, in the author’s opinion, is not worth the consequences. First, it opens the door for similar actions on either side, which is fraught with volunteers from NATO appearing in sufficient numbers. Second, this would cause logistical and communication problems. Third, a significant part of the Russian mass consciousness will perceive such a step as a weakness of the Kremlin, failing to complete the SMO without external assistance.

That is why the author believes that the consequences of the Russian president’s visit to the DPRK are unlikely to have a quick and direct impact on the course of the special military operation. Moreover, in any case, the implementation of the summit decisions will take some time, and the more extensive they are, the more time will be needed to put them into practice. And given the international situation, it will be difficult to separate the long-term consequences of the summit from the reaction to a possible change in the current situation.

Anyway, when Vladimir Putin’s visit to North Korea takes place, this will be a landmark demonstration of the new level of relations between the two nations and Moscow’s diplomatic support for Pyongyang. Specific agreements may well be classified as secret, which is why “Scheherazade stops the allowed speeches,” preferring to deal with the analysis of events that have already taken place.