Multilateralism in the Era of Weak Institutions

(votes: 8, rating: 4.88) |

(8 votes) |

Ph.D. in History, Academic Director of the Russian International Affairs Council, RIAC Member

“Nothing is possible without men; nothing is lasting without institutions.” The famous quote of Jean Monnet looks outrageously outdated, if not insulting, in terms of gender, but it is otherwise still quite valid and can be used when addressing fundamental problems of governance and its future. Efficient governance—both domestic and international—needs strong, predictable and lasting institutions capable of managing seemingly chaotic economic, social, political and other transactions within complicated settings, building coherent and transparent regimes, brokering acceptable compromises between actors with diverging interests and priorities.

In the international domain, there is an unquestionable interconnection between institutions and multilateralism. The overwhelming majority of international institutions are multilateral, not bilateral; their cumulative impact on global politics, economy and security can hardly be overestimated. Multilateral institutions offer appropriately structured platforms for nation-states to work on common norms of behavior, to advance complex cooperation projects, to address shared challenges and to make decisions on joint actions.

Only strong and well-established institutions can set rules of behavior that most of international actors are ready to accept as legitimate and fair. At the same time, strong and enduring institutions are in the best position to provide ‘diffuse reciprocity” that facilitates asymmetrical concessions allowing to reach compromises on important politically divisive or sensitive burden-sharing issues. Moreover, only strong institutions are capable to enforce their decisions on parties engaged in multilateral negotiations and to impose meaningful penalties on undisciplined actors for their non-compliance. It would not be an over exaggeration to say that multilateral institutions constitute the skeleton of the international system preventing the system from falling apart.

There are many reasons to believe that the era of intense geopolitical great power confrontation, which the world recently entered, will also imply a protracted period of relatively weak and even impotent international institutions with their authority and ability to contribute to building a new world order being significantly undermined. This weakness of international institutions is often perceived as a serious obstacle to promote efficient multilateralism in an increasingly diverse and poorly governed world. With little hope in further empowering institutionalized multilateralism nation-states are more likely to pursue their immediate egotistic interests through unilateral actions or through bilateral transactional arrangements. This trend is associated with multiple negative repercussions: economic protectionism, trade wars and unilateral sanctions, accelerating arms race, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, new regional crises and military conflicts, the rise of international terrorism, aggravation of global problems, climate change consequences including, social inequalities and resource deficits, etc.

In this paper, the author does not try to refute this assumption, instead, he offers a couple of qualifications to it. First, institutionalized multilateralism has never been particularly strong within the bipolar or the unipolar systems. Most of international institutions of the XX century were pseudo-multilateral rather than truly multilateral; their respective strengths and efficiency were nothing but a reflection of the power and of the political will displayed by the hegemonic actors.

Second, the ongoing weakening of international institutions is not universal: it affects mostly institutions with a broad mandate, highly diverse membership, high budgets and complicated decision-making procedures. Institutions with more focused agendas, more homogeneous memberships, with modest budgets and flexible procedures are in a better position not only to survive, but also to have a meaningful impact on the international system. The perceived crisis of institutionalized multilateralism is accompanied by a real boom in the new institution building, which suggests that during the era of geopolitical tensions institutionalized multilateralism still remains in high demand.

Finally, the apparent weakness of institutions might well be a blessing in disguise in the sense that it opens multiple opportunities for experimenting with new unorthodox forms of multilateral cooperation that were not available or were not popular in the era of predominantly rigid, hierarchical and inflexible institutions of the XX century. This is not to say that the institutional weaknesses of today should be embraced and encouraged as an asset, but they should probably be accepted as an integral and indispensable part of the world order mysterious metamorphosis turning an antediluvian caterpillar into a post-modern butterfly.

“Nothing is possible without men; nothing is lasting without institutions.” The famous quote of Jean Monnet looks outrageously outdated, if not insulting, in terms of gender, but it is otherwise still quite valid and can be used when addressing fundamental problems of governance and its future. Efficient governance—both domestic and international—needs strong, predictable and lasting institutions capable of managing seemingly chaotic economic, social, political and other transactions within complicated settings, building coherent and transparent regimes, brokering acceptable compromises between actors with diverging interests and priorities.

International Multilateralism in a Non-Hegemonic World

In the international domain, there is an unquestionable interconnection between institutions and multilateralism. The overwhelming majority of international institutions are multilateral, not bilateral; their cumulative impact on global politics, economy and security can hardly be overestimated. Multilateral institutions offer appropriately structured platforms for nation-states to work on common norms of behavior, to advance complex cooperation projects, to address shared challenges and to make decisions on joint actions.

Only strong and well-established institutions can set rules of behavior that most of international actors are ready to accept as legitimate and fair [1]. At the same time, strong and enduring institutions are in the best position to provide ‘diffuse reciprocity” that facilitates asymmetrical concessions allowing to reach compromises on important politically divisive or sensitive burden-sharing issues [2]. Moreover, only strong institutions are capable to enforce their decisions on parties engaged in multilateral negotiations and to impose meaningful penalties on undisciplined actors for their non-compliance [3]. It would not be an over exaggeration to say that multilateral institutions constitute the skeleton of the international system preventing the system from falling apart.

There are many reasons to believe that the era of intense geopolitical great power confrontation, which the world recently entered, will also imply a protracted period of relatively weak and even impotent international institutions with their authority and ability to contribute to building a new world order being significantly undermined [4]. This weakness of international institutions is often perceived as a serious obstacle to promote efficient multilateralism in an increasingly diverse and poorly governed world. With little hope in further empowering institutionalized multilateralism nation-states are more likely to pursue their immediate egotistic interests through unilateral actions or through bilateral transactional arrangements. This trend is associated with multiple negative repercussions: economic protectionism, trade wars and unilateral sanctions, accelerating arms race, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, new regional crises and military conflicts, the rise of international terrorism, aggravation of global problems, climate change consequences including, social inequalities and resource deficits, etc.

In this paper, the author does not try to refute this assumption, instead, he offers a couple of qualifications to it. First, institutionalized multilateralism has never been particularly strong within the bipolar or the unipolar systems. Most of international institutions of the XX century were pseudo-multilateral rather than truly multilateral; their respective strengths and efficiency were nothing but a reflection of the power and of the political will displayed by the hegemonic actors.

Second, the ongoing weakening of international institutions is not universal: it affects mostly institutions with a broad mandate, highly diverse membership, high budgets and complicated decision-making procedures. Institutions with more focused agendas, more homogeneous memberships, with modest budgets and flexible procedures are in a better position not only to survive, but also to have a meaningful impact on the international system. The perceived crisis of institutionalized multilateralism is accompanied by a real boom in the new institution building, which suggests that during the era of geopolitical tensions institutionalized multilateralism still remains in high demand.

Finally, the apparent weakness of institutions might well be a blessing in disguise in the sense that it opens multiple opportunities for experimenting with new unorthodox forms of multilateral cooperation that were not available or were not popular in the era of predominantly rigid, hierarchical and inflexible institutions of the XX century. This is not to say that the institutional weaknesses of today should be embraced and encouraged as an asset, but they should probably be accepted as an integral and indispensable part of the world order mysterious metamorphosis turning an antediluvian caterpillar into a post-modern butterfly.

Limitations of traditional institutionalized multilateralism

During the Cold War, the task of building and maintaining strong international institutions rested primarily on the shoulders of the main hegemonic actors. A very small group of great powers designed the post-Second World War global order according to their wishes and interests. The multilateral United Nations system was to a large degree a less than perfect compromise between Washington, London and Moscow with a limited involvement of the two other future permanent members of the UN Security Council. The WW2 victorious countries considered for themselves the right of veto and successfully imposed that norm on the international community.

The United States created NATO as a formally multilateral defense alliance, but for a long time—at least, until 1960s—nobody among the US European partners was in a position to question or to challenge the US leadership positions within the Alliance [5]. When in 1963 General de Gaulle tried to introduce some elements of real multilateralism into NATO’s nuclear decision-making, Secretary of State Dean Rusk interpreted these attempts as a clear intention to undermine the core foundations of the Alliance. At best, NATO served as a school of multilateralism, gradually spreading the notion of collective defense among member-states [6]. The Soviet hegemony within the formally multilateral Warsaw Pact was even more explicit and unquestionable [7]. The strength of formally multilateral Cold War era institutions fully depended on the political and military power of their respective founders and leaders.

This is why in a truly bipolar system multilateralism was always relative, incomplete and subject to criticism. It would probably be more precise to call it pseudo-multilateralism that implied rigid hierarchies camouflaged by formally multilateral mechanisms [8]. Multilateral institutions within such a system may look very strong, highly efficient and representative, but in the end of the day their strength and efficiency are a function of the power, the good or evil will of their hegemonic masters (leaders). When the Soviet Union started to unravel, the Warsaw Pact Organization fell apart almost overnight. The odds are that NATO would not have lasted for a long time either, if the United Stated for this or that reason had decided at some point to move out of Europe, as populists like Donald Trump intimidated the US European allies.

The same limitations were typical for most of multilateral institutions during the first decade after the end of Cold War—the US global hegemony put a deep imprint on a broad spectrum of such institutions raging from the United Nations and G7/8 to WTO, IMF and IBRD. Quite often, institutionalized multilateralism of 1990s implied nothing but appropriate mechanisms to convert unilateral US positions into formally collegial and therefore more legitimate decisions. In short, it would be fair to say that the unipolar system inherited from its bipolar predecessor the model of pseudo-multilateral international institutions and developed it even further [9].

Assessing the diverse and somewhat contradictory experience of institutionalized multilateralism in the XX century, one should also keep in mind that during both bipolar and unipolar stages of the international system development, there were large and potentially quite explosive parts of the world that experienced an evident deficit of multilateralism. No strong multilateral institutions emerged in the Northeast or in South Asia, in the MENA region or in Sub-Saharan Africa. This deficit might have indeed contributed to numerous security and development problems of these regions, but it was not the most important factor defining the historic trajectories of these regions. Europe with many multilateral institutions was not that different from the Northeast Asia, where such institutions never came to fruition [10]. The Cold War experience suggests that institutionalized multilateralism might be a desirable, but not an indispensable mechanism to maintain regional peace and stability; its role was seldom decisive and its involvement was rarely insurmountable.

This raises the question of how one measures the strength of institutional multilateralism and its specific contribution to international security and development [11]. In the second half of the XX century the strength of multilateral institutions was routinely measured not by their ability to reach compromises among actors with diverging interests or to resolve difficult international problems (real disagreements among members were continuously suppressed in one way or another), but rather by the degree of their institutional development. In many ways institutional development including governance structure, financial stability, stakeholder engagement, compliance and accountability—was regarded as a goal in itself. Consequently, the international system favored well-developed organizational structures with multiple layers of bureaucracies, complicated decision-making procedures, systems of diverse linkages that allowed the participating actors to balance unilateral concessions in one field by getting compensations in another field. Those institutional arrangements looked like an optimal solution for a relatively static system with slow and mostly marginal changes affecting the global balance of powers.

Another important feature of XX century multilateral institutions was that most of them happened to be value-based. Of course, there were important exceptions (United Nations, CSCE, ASEAN, OIC, OAS, AU to name a few), but these exceptions were not in plenty. During the Cold War, with the world divided into two blocks opposing each other, multilateral arrangements and mechanisms implied commonality of fundamental values among participating parties. It was usually ‘us’ against ‘them’: multilateralism within blocks (NATO—Warsaw Pact, European Union—COMECON) seldom extended to relations between the blocks. Since the two blocks were almost completely separated from each other, the whole idea of ‘global commons’ had very limited meaning in the deeply divided world [12]. Needless to say, shared fundamental values within multilateral international institutions were a major facilitator in reaching compromises on divisive matters.

After the Cold War the value-based nature of key multilateral institutions became even more explicit and indisputable. The predominant assumption in the world was that all the international actors should sooner or later gravitate to the Western liberal political, social and economic models and that the question was only about the specific trajectories and the pace of the predetermined transition. Remaining disagreements and conflicts among states were looked upon as residual legacies of history that had to be resolved almost automatically in the process of the comprehensive multidimensional modernization. In this context, multilateral institutions (such as OSCE and the Council of Europe) were perceived as important instruments for values transfer from mature liberal democracies to emerging democratic nations. Such a transfer had never constituted a coherent long-term strategy of the West, but it was nevertheless regarded as a prerequisite for a successful proliferation of multilateralism in the unipolar liberal world [13].

Furthermore, the XX century system of multilateral international institutions was predominantly state-based (government to government based). Some non-state institutions (e. g. large transnational corporations, powerful civil society organizations, religious movements, education and R&D communities) from time to time tried to deprive nation-states from their monopoly on institutionalized multilateral arrangements, but these attempts had only marginal success [14]. States were exclusive participants to the most important multilateral agreements, regimes and institutions with other actors (the private sector, NGOs, Universities, etc.) being much more in the role of deal-takers, rather than deal-makers. A limited number of actors with multiple common characteristics helped to keep the system in relative order and to make international institutions look strong and efficient.

However, this model of institutionalized multilateralism had to face a serious trail once the overall environment started rapidly changing. The changing balance of power in the world along with the growing diversity of social and political trajectories of national development exposed many limitations of the pseudo-multilateral international system.

Challenges of the XXI century

2022: End of the End of History

In the beginning of the XXI century, it became clear that the very foundations of the old institutionalized multilateralism were ill suited to serve the new international realities and that the system built on these foundations started crumbling. The US hegemony demonstrated its fragility on many occasions; a brief ‘unipolar moment’ resulted in an imperial overstretch and a subsequent US geopolitical retreat or, at least, US attempts at strategic retrenching, particularly under the Obama and Trump Administrations. It was also argued that main Western multilateral institutions were getting close to their natural geographical and functional limits [15]; both NATO and the EU had to face numerous challenges to their efficiency and even to their integrity. For instance, in 2003 the United States failed to get support for its military operation in Iraq not only from the UN Security Council, but also from some of the key NATO allies. As a result, President George W. Bush had to create an ad hoc ‘coalition of the willing’ to shoulder US efforts; not surprisingly, the legitimacy of the US-led intervention was broadly questioned.

A less dramatic, but arguably even more important shift took place in the global economy. After having failed to impose its national agenda within the WTO framework, The United States and the European Union shifted their emphasis from seeking comprehensive global arrangements to forging exclusive bilateral trade agreements or limited minilateral deals with select partners [16] . This move plunged global economic and financial institutions—not only WTO, but also IMF and IBRD into a deep crisis of legitimacy and paved the way for the future regionalization of the global economy.

Since political liberalism had not become the universal value system willingly accepted by all international actors, it became increasingly evident that multilateral institutions based on the formerly assumed ‘convergence of values’ or rather on the expectation that the Western liberal values would become universally accepted are likely to enter an uphill battle. The overall monistic view of ‘modernity’ associated with the West started losing its former attraction opening room to alternative versions of ‘modernity’ [17]. Even in Western counties the traditional liberal values were exposed to growing criticism from illiberal right-wing and left-wing populists [18].

At the same time, with more and more issues spilling over from the domestic political space to the international dimension, nation states showed less and less capacity to handle the global agenda successfully on their own, without a broader involvement of non-state players. This important change took place in both security and development fields. For instance, nowadays it is hardly possible to imagine how the problems of chemical weapons or of climate change can be successfully resolved without engaging the private sector or civil society institutions. Both groups of new international actors are getting more and more reluctant to be considered as mere extensions nation-states or as obedient tools in the capable hands of respective national governments. City and regional governments, municipalities and local authorities also entered the international domain in a much more confident and assertive way than ever before [19]. Non-state actors started insisting on their independent roles in international relations further eroding the legitimacy of pure intergovernmental international organizations of the past.

One can conclude that due to all the above-mentioned developments the humankind has indeed entered an extended period of relatively weak multilateral international institutions in critically important areas of security and development. On top of substantive changes in the international system, there are a couple of additional reasons to conclude that with some notable exceptions, existing multilateral institutions will continue to experience significant problems and their role in building a new world order will therefore be limited though the need for their engagement may be more evident than ever before.

The rapidly shifting balances between global and regional players make it harder to maintain or to properly adjust delicate equilibriums within complex multilateral arrangements that are often essential for the decision-making mechanisms, personnel policies and funding priorities. Descending powers usually reject the concept of ‘graceful decline’ and insist on status-quo preservation to the extent possible, while impatient ascending powers stand for swift and radical adjustments within such arrangements. Institutional inertia usually favors the former and incentivizes the latter to delegitimize institutions unwilling to reinvent or even to reassemble themselves. If China cannot expect rapid changes in quota systems and voting rights within INF or IBRD, it becomes incentivized to proceed with parallel multilateral financial and development institutions (like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank), where it could have more say and influence [20].

Another complicating factor is that it becomes increasingly difficult to measure changes in the nation-states balance of powers. We assume that the balance of powers is shifting, but how exactly is it shifting? In theory, there are many quantifiable indicators that should allow to measure changes with a high degree of precision [21] . In practice, relative weights of quantitative indicators correlate with a variety of qualitative ones that significantly distort the overall picture [22] and gives way for many self-serving value judgements and endless disputes about what constitutes ‘real’ power within the international system.

Historically, new multilateral arrangements in Europe or in the world followed large-scale international conflicts that allowed to fix the new balance of powers in a decisive way. That was the case after the Thirty Years’ War (the Westphalian System), the Napoleonic Wars (the Vienna Concert), the First World War (the Versailles System) and the Second World War (the Yalta-Potsdam System). However, today a direct military conflict between main international actors would almost inevitably turn into a global nuclear war that no actor can afford. Therefore, instead of traditional military conflicts in order to test the changing balance of powers major actors use a variety of substitutes—proxy wars, hybrid wars, economic wars, and so on. The good thing about such substitutes is that allow to control risks and to limit costs of the confrontation, but the bad thing is that do not allow to measure the changing balance of powers in an ‘ultimate’ way. All these proxy and hybrid wars can last for a long time without defining the finite winner [23]. In the absence of the latter, a stable multilateral arrangement is hard to achieve.

One can argue that specific multilateral balances do not matter that much these days, since the world is once again gradually moving towards economic, technological and even military bipolarity [24]. If indeed the old bipolar system could be restored in its initial integrity, the world would arguably also go back to the Cold War pseudo-multilateral institutions concealing the new bipolar core of the international system [25]. To some extent, this process does take place in the West, with the United States restoring its former position of the indisputable leader within NATO, AUKUS, the US-Japanese-ROK alliance and in other formally multilateral settings. Some of these institutions are growing in relative strengths as well as in numbers of their members.

However, a global return to pseudo-multilateralism of the second half of the last century type looks highly improbable because many mid-size powers of the Global South are considering the current turmoil in the international system not only as a challenge, but also as an opportunity to increase their space for maneuvering and to enhance their stature within the system [26]. This is why, for instance, it would be wrong to draw parallels between the enlargement of NATO and the enlargement of BRICS—in the first case, we are talking about a well-structured, heavily bureaucratized pseudo-multilateral defense alliance, while in the second case, we approach a loose club of assorted members with no rigid member commitments to each other, not institutional foundation and no hierarchy within the club.

The high level of economic interdependence in the modern world, unseen in the bilateral system of the XX century, is another factor guaranteeing the retention of certain elements of multipolarity or polycentrism in the foreseeable future [27]. Many of intentional actors are and will remain extremely reluctant to choose sides in the US-China confrontation for pure economic reasons. However, the resilience of multipolarity can hardly be a consolation to champions of multilateralism—multipolarity is not necessarily followed by meaningful multilateralism.

The problems of institutionalized multilateralism are complicated by the persistent institutional fatigue in the world with most of actors unwilling to invest plenty of political and financial resources into building new institutions or in reforming the old ones. Many people in all parts of the world believe that the principle of multilateralism has not met their expectations and should therefore be put on a shelf until better times or even abrogated altogether [28]. This is one of the reasons why many of new multilateral initiatives face hard problems in their attempts to acquire solid institutional foundations similar to what their predecessors inherited from the XX century. It seems that many of these initiatives are doomed to remain embryonic for the foreseeable future.

One should probably add that today in many countries political leaders simply have no solid powerbase that would allow them to make long-term investments into institutionalized multilateralism, when the likely returns on these investments are not going to come soon enough. What we observe can be described as a long-term decay of traditional mechanisms of domestic social and political mobilization caused by the continuous social stratification and the spread of new means of social communication. In many countries, traditional political parties are losing their grip on power, legitimacy of core state institutions and procedures is increasingly questioned. The old political border lines between the Right and the Left, between Conservators and Liberals, even between Mainstream and Marginals become less stable. As a result of these trends, nation-states are more and more often governed by very fragile political coalitions that are extremely vulnerable to even minor fluctuations of the public sentiments and preferences. These worrisome trends raise concerns not only among experts, but also of general public [29].

On course, it would be hard to expect such political coalitions to pursue a consistent and responsible foreign policy including long-term commitment to institutionalized multilateralism. Domestic limitations and constrains push nation-states in the direction of transactional and situational arrangements that in many ways compromise the essence of a true multilateralism. The level of uncertainty in international relations continues to grow; the odds are that this trend will continue in future.

A bumpy road ahead

The World in 2035: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

The likely repercussions of a continuously weakening multilateral institutions for the global and regional governance are manifold and are hardly fully predictable at this point. However, some of them are already looming on the horizon.

Weak institutions with questionable legitimacy and highly limited enforcement capacities feed temptations of unilateralism by actors that feel no meaningful constraints to their freedom of action. If international norms can be broken with impunity, they are going to be broken more and more frequently [30]. The emphasis on national sovereignty at the expense of interdependence becomes stronger; nation-states shape their policies based on narrowly defined national interests to the detriment of remote and seemingly abstract global commons. Appeals to inalienable sovereign rights of nation-states become an excuse to relieve these states from obligations under international agreements and multilateral commitments. It is indicative that most of ascending powers of the Global South are reluctant to join any legally binding multilateral political or defense alliances—not only with potential partners in the West, but also with their close neighbors [31]. These attitudes to international rights and responsibilities of national leaders might lead to a rapid and irreversible erosion of international multilateralism as we used to know it.

in the absence of strong universal institutions, multilateralism might be reduced to ad hoc minilateralism or to multilateralism a la carte. These forms of ‘simplified’ multilateral arrangements with no strong institutional foundations are gaining popularity and recognition—particularly in the regions of the Global South, where traditional institutionalized multilateralism does not have deep roots [32] and where classical multilateral institutions experience significant problems (like it is the case with SAARC, ECOWAS or GCC). Such a selective and arguably self-serving approach to multilateralism might have its practical advantages, but it also contains many risks and has significant shortcomings [33]. With no strong institutional base, multilateralism can degenerate to purely transactional incremental agreements with no long-term commitments or ‘diffuse reciprocity’ expectations. Minilateralism seldom properly addresses challenges of compliance, verification, accountability and so on. It also tends to focus on ‘low hanging fruits’ rather than on really tough and divisive problems. One can argue that minilateralism should be considered positive as a step in the direction of the true institutionalized multilateralism, but it turns negative, if it is perceived as a viable long-term substitution of the latter.

It seems to be fair to conclude that no alternative to institutionalized multilateralism has emerged since the end of the Cold War. It remains highly unlikely that humankind can achieve an acceptable level of global or regional governance if major actors willingly or unwillingly limit themselves to a mixture of unilateralism and bilateral agreements accompanied by ad hoc non-institutionalized arrangements. The statistical probability of a harmonious world order emerging spontaneously from the Brownian motion of atomized international actors is likely to be not higher than the probability of life emerging spontaneously from non-organic molecules, which is considered b most scientists to be very low.

The only plausible alternative to a robust multilateralism is not a restoration of an old bipolar, unipolar or multipolar order, but a global disorder with no agreed-upon norms, procedures and hierarches of power. One would need a real stretch of the imagination to envision a stable and sustainable international system based exclusively on the balance of power, no matter how this balance is fixed and measured [34].

The disorderly world in an era of resource deficits, rapid climate change, unprecedented migration flows and uncontrolled technologies cannot survive for too long. If the ongoing demise of multilateralism continues, our civilization is doomed to experience a global crisis of an epic scale [35]. All the complications and shortcomings notwithstanding, multilateralism seems to be the only way to move ahead, even if such movement is slow and inconsistent. The challenge is to agree on a number of baseline fundamentals in a more and more diverse post-modern world. Multilateralism based exclusively on values, on stature, on immediate interests or even on balance of power will not necessarily work in the new environment. In any case, multilateralism of the future will have many faces and many embodiments and this fully applies to its institutionalized incarnations [36].

The new model of institutionalized multilateralism has to be efficient, flexible, adaptive, inexpensive, transparent, democratic, accountable and representative—these criteria are hard to combine. The odds are that we will see a growing variety of overlocking institutions and weak institutionalized regimes that will often duplicate each other, compete for resources and recognition, but also cooperate with each other within broad situational coalitions. Many of them will not demonstrate the expected resilience or sustsiability, some might remain dormant for a long time and wake up when and if there is an articulated political or public demand for their services. To rephrase a well-known quote of Charles Darvin, it will not be the strongest multilateral institution that survives and flourishes, nor the most representative or best funded, but the one most responsive to change.

State leaders around the world should be ready to advance institutionalized multilateralism without a benign hegemon to shoulder their efforts. It would be great to see the United States reemerging as a strong supporter of institutionalized multilateral approaches or to watch China building up its appetite for institutional solutions, but these fortunate developments should not be taken for granted. The continuous struggle between the descending and the ascending superpowers is likely to produce incentives for revisiting old pseudo-multilateral institutional patterns and to constrain US and China’s political and material investments into strong and assertive multilateral institutions [37]. Both counties will have to go through fundamental domestic political changes before their overall attitudes to the genuine institutionalized multilateralism may mature.

Moreover, other big powers like India, Russia or Brazil are not likely to lead the world towards a new model of institutionalized multilateralism either. They are too used to traditional patterns of asymmetrical interdependence and they are tempted to use their comparative advantages in the format of bilateral relations with their relatively smaller and weaker neighbors and more distant partners. These powers, as well as US and China, are more likely to try to resurrect the old “spheres of influence” based models of pseudo-multilateralism that existed in the previous century. Members of existing genuinely multilateral arrangements like EU or ASEAN, which have already accumulated a lot of experience in various formats of genuine institutionalized multilateralism, might be in a better position to pioneer new multilateral models [38]. This is why their engagement into the ongoing discourse on multilateralism is particularly important.

Diplomats and experts have to figure out how to apply multilateral models to an environment of relatively weak international institutions and eroding hierarchies. The above-mentioned institutional fatigue in the world today is not going to disappear anytime soon. To successfully deal with it, institutionalized multilateralism has to demonstrate that it can become nimbler, more decentralized, cost-efficient and accountable [39]. A key challenge for multilateral institutions will be to reach out to new constituencies of stakeholders (including aspiring non-state actors) and to engage the always skeptical and fickle public.

Prepare for the Worst and Strive for the Best. Russia’s and China’s Perceptions of Developments in International Security

In many important areas institutionalized multilateralism should not imply communality of values as a precondition; it will rather have to reflect convergence of specific interests displayed by diverse actors. The old mantra that international multilateralism is a direct function of political liberalism as the dominant ideology of major players should be rejected as obsolete and non-practical: multilateralism of the 21st century will be universal only if it can serve a value-pluralistic world. At the same time, the international community could use institutionalized multilateralism as a tool to bridge or to narrow many value gaps that exist in the modern world. In other words, communality of values should not be a starting point on the road to multilateralism or an indispensable precondition for it, but rather the destination in the end of this road. Keeping this inevitable impact of multilateral cooperation on participating parties’ values might make pragmatic multilateral compromises more acceptable to actors that tend to put their values above immediate interests [40]. In times of swift changes project-driven multilateralism might have a comparative advantage over mission-driven multilateralism. Focusing on specific, incremental issues may matter more than prioritizing long-term aspirations and maintaining broadly defined areas of activities.

A successful institutionalized multilateralism has to be inclusive. It is no longer only or even primarily about relations between states, but it has to embrace the business sector, civil society and other private and public players. Of course, there are no ideal solutions for transnational private-public partnerships operating in various fields of security and development; in each of these fields there are specific models of engagement [41]. Still, the overall role of inclusivity is likely to grow in future and the art of broad and diverse coalitions building is likely to become one of the main comparative advantages of successful leaders of the future. Institutions allowing diversity of participants including non-state actors will have visible advantages over institutions with rigidly defined memberships; one of the most challenging tasks would be to blur the red line between membership and partnership and to customize engagement of external actors (this is why we observe emerging formats like BRICS+ [42] and QUAD+ [43]).

This particular model has many shortcomings and inherent deficiencies—it is doomed to be very fluid, situational, inconsistent and fragile. It will inevitably contain an unpleasant tradeoff between inclusiveness and efficiency. It is clearly not a solution for all seasons. However, it might still be the best option for humankind that we can count on for the nearest future.

The report presented at Fudan University Conference on Global Governance, April, 25–27, 2024, Shanghai.

1. Mogami Toshiki. Legality, Legitimacy, and Multilateralism // From No. 2, Vol. XLVIII, “Pursuing Peace: Commemorating Dag Hammarskjöld”, 2011. United Nations, UN Chronicle. URL: https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/legality-legitimacy-and-multilateralism

2. Larry Kramer. Collaboration and “Diffuse Reciprocity” // Stanford Social Innovation Review. 24.04.2014. URL: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/collaboration_and_diffuse_reciprocity#

3. Barkin, J. Samuel. “Time Horizons and Multilateral Enforcement in International Cooperation.” International Studies Quarterly, vol. 48, no. 2, 2004, pp. 363–82. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3693578

4. Jean-Jacques Hallaert. The Tragedy of International Organizations in a World Order in Turmoil // European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE), July 2020. URL: https://ecipe.org/publications/tragedy-of-international-organizations/

5. Transforming NATO in the Cold War Challenges beyond deterrence in the 1960s. Andreas Wenger, Christian Nuenlist, Anna Locher (eds.) // CSS Studies in Security and International Relations. Routledge, Oxon-New York, 2007. URL: https://phpisn.ethz.ch/www.php.isn.ethz.ch/publications/newlit/documents/transforming-nato.pdf

6. Steve Weber. Shaping the postwar balance of power: multilateralism in NATO // International Organization

Vol. 46, No. 3 (Summer, 1992), pp. 633-680. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2706991

7. Robin Remington. The Warsaw Pact: Institutional Dynamics Within the Socialist Commonwealth // The American Journal of International Law. Vol. 67, No. 5 (November 1973), pp. 61-64. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25660479

8. The term ‘pseudo-multilateralism’ these days is commonly used in China to describe new US-led multilateral bodies like G7, Quad, Five Eyes, etc. See: Zou Zhibo. Cast aside pseudo-multilateralism // China Daily. 21.06.2021. URL: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202106/21/WS60cfd522a31024ad0baca3c3.html

9. The relations between unipolarity and unilateralism (and between multipolarity and multilateralism) are not linear: unipolarity does not exclude multilateral arrangements, while multipolarity does not prevent unilateralism. See: John Van Oudenaren. Unipolar versus Unilateral // Hoover Institution or Stanford University. 1.04.2004. URL: https://www.hoover.org/research/unipolar-versus-unilateral. Still, there are many reasons to argue that there can be no full-scale multilateralism in a unipolar world.

10. Ki-Joon Hong. Institutional Multilateralism in Northeast Asia: A Path Emergence Theory Perspective // North Korean Review, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring 2015), pp. 24-41. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43908954

11. Sommerer, T., Squatrito, T., Tallberg, J. et al. Decision-making in international organizations: institutional design and performance // Review of International Organizations, volume 17, 815–845 (2022). URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-021-09445-x

12. Surabhi Ranganathan. Global Commons. European Journal of International Law, Volume 27, Issue 3, August 2016, Pages 693–717, URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chw037

13. Falk, R. Liberalism at the Global Level: Solidarity vs. Cooperation. // In: Hovden, E., Keene, E. (eds) The Globalization of Liberalism. Millennium. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2002. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230519381_5

14. Halliday, F. The Romance of Non-state Actors. // In: Josselin, D., Wallace, W. (eds) Non-state Actors in World Politics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. 2001. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781403900906_2

15. Michael O’Hanlon. NATO’s Limits: A New Security Architecture for Eastern Europe // Survival. Volume 59, 2017 - Issue 5, p. 7 – 24. URL: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00396338.2017.1375215

16. Walden Bello. The Rise and Fall of Multilateralism // Dissent Magazine. Spring 221. URL: https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/the-rise-and-fall-of-multilateralism/

17. Seth, S. Is Thinking with ‘Modernity’ Eurocentric? Cultural Sociology, 10(3),2016, p. 385-398. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975516637203

18. Sylvie Kauffmann. The West’s Schism Over Liberal Values // The New York Times. 22.09.2017. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/22/opinion/west-liberal-values.html

19. Wijninga, Peter, Willem Theo Oosterveld, Jan Hendrik Galdiga, Philipp Marten, Eline Chivot, Maarten Gehem, Emily Knowles, et al. // State and Non-State Actors: Beyond the Dichotomy. Edited by Joris van Esch, Frank Bekkers, Stephan De Spiegeleire, and Tim Sweijs. Strategic Moitor 2014: Four Strategic Challenges. Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep12608.8.

20. David Dollar. Reluctant player: China’s approach to international economic institutions // The Brookings Institution Commentary. 14.09.2020. URL: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/reluctant-player-chinas-approach-to-international-economic-institutions/

21. William B. Moul. Measuring the 'Balances of Power': A Look at Some Numbers // Review of International Studies, vol. 15, no. 2, 1989, pp. 101–21. JSTOR, URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20097174.

22. Christopher McCallion. Grand Strategy: the Balance of Power // Defense Priorities. 16.04.2024. URL: https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/grand-strategy/the-balance-of-power

23. Cian O'Driscoll. Can wars no longer be won? // The Conversation. 2.12.2019. URL: https://theconversation.com/can-wars-no-longer-be-won-126068

24. Cliff Kupchan. Bipolarity is Back: Why It Matters // Eurasia Group. 2.02.2022. URL; https://www.eurasiagroup.net/live-post/bipolarity-is-back-why-it-matters

25. Emil Avdaliani. Ukraine War Ushers in a New Bipolar World Led by the US and China // Henry L. Stimson Center. 22.05.2023. URL: https://www.stimson.org/2023/ukraine-war-ushers-in-a-new-bipolar-world-led-by-the-us-and-china/

26. Strategic interdependence: Europe’s new approach in a world of middle powers // European Council on Foreign Relations Brief. 3.10.2023. URL: https://ecfr.eu/publication/strategic-interdependence-europes-new-approach-in-a-world-of-middle-powers/

27. Kupchan, C. Bipolarity is Back: Why It Matters. The Washington Quarterly, 2021, 44(4), 123–139. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2021.2020457

28. Amrita Narlikar. The malaise of multilateralism and how to manage it // Observer Research Foundation. 23.1.2020. URL: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/the-malaise-of-multilateralism-and-how-to-manage-it

29. Brooke Auxier. 64% of Americans say social media have a mostly negative effect on the way things are going in the U.S. today // Pew Research Center.15.10.2020. URL: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-read/2020/10/15/64-of-americans-say-social-media-have-a-mostly-negative-effect-on-the-way-things-are-going-in-the-u-s-today/

30. Scott N. Romaniuk, Francis Grice. Norms, Norm Violations, and IR Theory // E-International Relations. 15.11.2019. URL: https://www.e-ir.info/2018/11/15/norms-norm-violations-and-ir-theory/

31. Comfort Ero. The Trouble With “the Global South” // Foreign Affairs. 1.04.2024. URL: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/trouble-global-south

32. Nickolay E. Mladenov. Minilateralism: A concept that is changing the world order //

33. Aarshi Tirkey. Minilateralism: Weighing the Prospects for Cooperation and Governance // Observer Research Foundation. 1.09.2021. URL: https://www.orfonline.org/research/minilateralism-weighing-prospects-cooperation-governance

34. John R. Bolton. A World without Rules // National Review, 20.01.2022. URL: https://www.nationalreview.com/magazine/2022/02/07/a-world-without-rules/

35. MIT Predicted in 1972 That Society Will Collapse This Century. New Research Shows We’re on Schedule // Environment Institute. 14.07.2022. URL: https://www.enviro.or.id/2023/07/mit-predicted-in-1972-that-society-will-collapse-this-century-new-research-shows-were-on-schedule/

36. Malcolm Chalmers. Which Rules? Why There is No Single ‘Rules-Based International System’ // RUSI. April, 2019. URL: https://axelkra.us/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/201905_op_which_rules_why_there_is_no_single_rules_based_international_system_web.pdf

37. Ngaire Woods. Multilateralism in the Twenty-First Century // Global Perspectives (2023) 4 (1). University of California Press. URL: https://online.ucpress.edu/gp/article/4/1/68310/195239/Multilateralism-in-the-Twenty-First-Century

38. Jason Young. Small states show the world how to survive multipolarity // East Asia Forum. 13.05.2020. URL: https://eastasiaforum.org/2020/05/13/small-states-show-the-world-how-to-survive-multipolarity/

39. Prato S, Adams B. Reimagining Multilateralism: A Long but Urgently Necessary Journey // Development (Rome). 2021;64(1-2):1-3. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8527287/

3. Anke Schwarzkopf. Values versus interests? The EU’s approach to multilateral negotiations at the United Nations // ARENA Centre for European Studies. University of Oslo. March, 2024. URL: https://www.sv.uio.no/arena/english/research/publications/arena-reports/2024/arena-report-2-24.html

40. Schäferhoff Marco, Campe Sabine, Kaan Christopher. Transnational Public-Private Partnerships in International Relations. Making Sense of Concepts, Research Frameworks and Results // SFB-Governance Working Paper Series, No. 6, DFG Research Center (SFB, Berlin, August 2007. URL: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/95431/WP6e.pdf

42. Expansion of BRICS: A quest for greater global influence? // European Parliament Think Tank Briefing. 15.03.2024. URL: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI%282024%29760368

43. Jagannath Panda. Making ‘Quad Plus’ a Reality // The Diplomat. 13.01.2022. URL: https://thediplomat.com/2022/01/making-quad-plus-a-reality/

(votes: 8, rating: 4.88) |

(8 votes) |

RIAC Working Paper No. 62 / 2022

2022: End of the End of HistoryThe conflict between Russia and the West is likely to drag on for decades, regardless of how and along exactly what lines the conflict in Ukraine ends

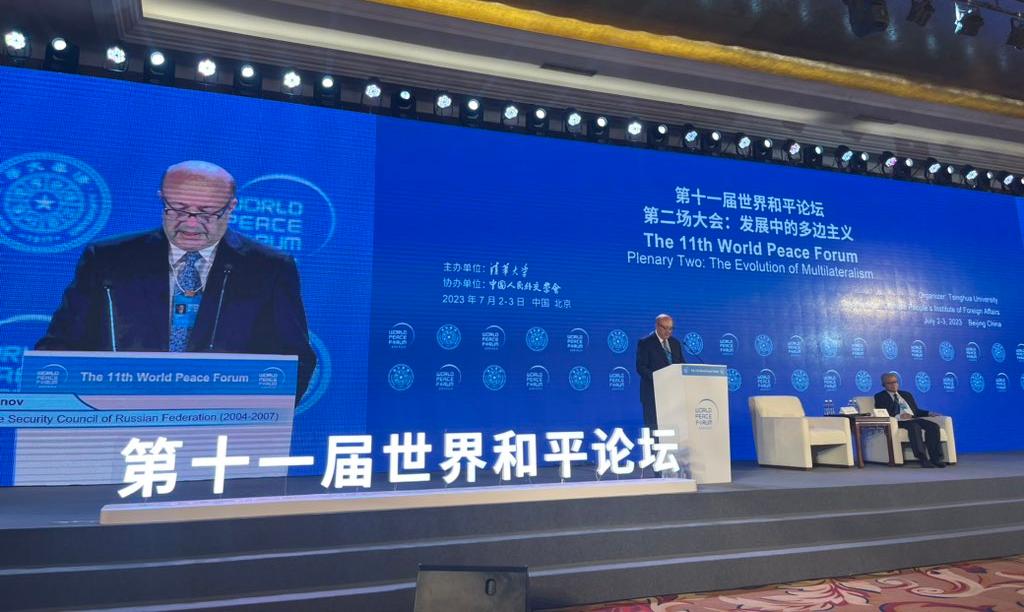

What Are the Core Benefits of Multilateralism at the Present Stage?Speech at the 11th Beijing World Peace Forum

Prepare for the Worst and Strive for the Best. Russia’s and China’s Perceptions of Developments in International SecurityInterview with Andrey Kortunov and Zhao Huasheng

The World in 2035: The Good, The Bad, and The UglyIs it possible to restore the acceptable level of global and regional governance on the “bottom-up” basis, that is, through a set of tactical, situational, transactional agreements on individual specific issues?