The U.S. global missile defense architecture is gradually built around nodal components, some of which cover East Asia. The Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMWS) is based on radar systems and a satellite constellation. Within the Pacific in particular, fixed stations are deployed in California and the Aleutian Islands, while mobile radars on floating platforms are deployed in the Marshall Islands and bases in Japan.

The highest density of missile defense can be provided by sea-based systems on warships with the Aegis BMDS. The characteristics of the latest modifications of the SM-3 Block IIa interceptors provide the capability of destroying various classes and types of missiles as well as low-orbit satellites at a range of more than 2,000 km and an altitude of more than 250 km.

The system developed in Japan over the past 20 years features a high degree of collaboration with the United States. The Republic of Korea has three Aegis BMDS destroyers equipped with interceptors (mostly SM-6). Seoul is also building an echeloned KAMD (Korean Air and Missile Defense) network largely based on the Patriots, harnessing the Israeli experience with the Iron Dome.

In 2018, the head of Russian diplomacy insistently urged Japan to enter into a dialogue about the U.S. plans to create a global missile defense system to prevent violation of Russia’s interests, in accordance with the principle of indivisible security. However, none has seen fit to respond to Russia’s well-grounded concerns and ensure the East Asia regional security sustainability. Under these circumstances, Moscow and Beijing’s increased focus on building up their own defense capabilities against a missile attack, particularly on cooperation in creating a unified ballistic missile defense system, can be considered quite justified.

Washington’s ambivalent approach to global strategic stability became clear back at the time of the New START signed in 2010. Despite Russia’s concerns, the document failed to enshrine any restrictions on the development of the U.S. air defense. Article XIV and Russian President’s statement stipulate that any buildup of the U.S. air defense capabilities in terms of quality and quantity falls within extraordinary circumstances threatening the ultimate interests of the Russian Federation and can then be seen as a ground for Russia’s withdrawal from the agreement.

As early as 2011, the State Duma warned U.S. partners against developing a missile defense system without Russia’s participation. Otherwise, any unilateral activity would be perceived as hostile, leading to Moscow’s withdrawal from the treaty. In February 2023, Russia suspended its participation in the New START, linking this decision to the direct involvement of NATO countries in the situation in Ukraine and strikes on Russian military and civilian facilities. The document expires on February 5, 2026, but the fate of the strategic offensive arms reduction process, given the completely opposite views on global stability in Moscow and Washington, is extremely vague. Interestingly enough, the U.S. State Department expressed in April 2024 its readiness to cancel countermeasures and fully implement the New START if “Russia returns to compliance.” Given the circumstances of Moscow’s freezing of the agreement and the unbending position of the Biden administration on Ukraine, this move is just an attempt to put a bold face on the matter.

The death trap of defense and offense

The 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM Treaty) enshrined the conditions of the Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) that Moscow and Washington agreed upon. Both sides proceeded from the relative openness of each other’s territories to the full power of the enemy’s nuclear capabilities as part of a rational approach to deterrence. There is an opinion that it was the deployment of defensive systems to protect the population that was destabilizing in the geopolitical environment of the Cold War [1]. Still, it is extremely difficult to accuse the Soviet Union of purposeful escalation or of seeking to secure the decision-making center by deploying an echeloned missile defense system around Moscow and the Central Industrial District just to get a carte blanche for a first strike. On the contrary, the developed structure of the Strategic Missile Forces, with their extremely distant nodes, prioritized the defense of the capital region, in full compliance with the Additional Protocol as of 1974.

As early as 1962, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara put forward the idea of relying on a counterforce strike aimed at destroying the enemy’s armed forces, mainly nuclear attack capabilities as well as command and control infrastructure. The Soviet Union rejected this concept, insisting on its own right to launch an unlimited crushing retaliatory strike against the aggressor. In fact, it was a counter-value-based version of the response. In the early 1960s, the Americans proceeded from the results of experiments based on war games with the use of computers, as R. Frykland puts it. Those experiments suggested the U.S. would win the war or achieve a most favorable settlement of the conflict in case of their refusal to destroy cities [2].

In the time of President Richard Nixon, the U.S. military initiated a new response strategy aimed at achieving superiority in the exchange of counterforce strikes. Under Ronald Reagan, those ideas were transformed into the concept of limited nuclear war. The Strategic Defense Initiative was declaratively aimed at reducing the ability of the USSR to retaliate, including through the development of missile defense.

In the 2000s, under the administration of George W. Bush, the idea of removing obstacles to an effective global security system by the United States prevailed. As Russian researcher Alexander Sergunin pointed out, Washington decided to use the “unipolar moment” that emerged after the end of the Cold War to consolidate the world dominance [3].

Russian experts V. Gelovani and A. Piontkovsky believe the “counterforce-countervalue strikes” pair essentially represents an extreme version of global nuclear war, the actual mutual suicide. However, this does not guarantee stability at lower escalation levels. For this reason, the authors put forward the idea of MAP stability (Mutual Assured Protection) on the basis of guaranteed protection against limited strikes for the opposing sides. As this logic runs, maintaining the capabilities of Russia and the United States, as stipulated by the current strategic arms agreements, still guarantees stability should someone deploy a missile defense system with the potential of intercepting up to 1/10th of the missile warheads.

However, the problem lies in the details. In the event of a complete collapse of the START regime, there will be no formal restrictions for Washington to increase the number of carriers and warheads. The fastest option is to return the charges from storage for their placement on intercontinental ballistic missiles, strategic bombers and submarine-launched ballistic missiles. In the opinion of the authoritative Russian military expert Vladimir Lata, which he expressed more than 10 years ago, the U.S. capabilities to rapidly build up forces for a first nuclear strike during the period of an escalation threat could be estimated at 73 carriers and 455 charges within 24 hours, and 121 carriers or 1,139 charges within 30 days. Of particular significance are the U.S. plans to deploy tactical nuclear weapons, including medium-range missiles, which further increases their strike potential. In this context, the development of missile defense as a clear counterforce poses a direct threat to the entire world.

Global plans with minimum justification

In December 2002, a presidential directive titled U.S. National Missile Defense Policy was adopted. It envisioned an echeloned infrastructure of land-, sea-, and air-based missile defense on a global scale. Most attention was paid to the advanced deployment of the means to intercept ballistic missiles of potential adversaries in the most dangerous directions – Eastern Europe and East Asia. With that said, Washington’s missile defense initiatives should be viewed exclusively as a stage in implementing the Prompt Global Strike concept, which relies on the simultaneous development of conventional precision weapons systems, nuclear deterrent forces, and missile defense. The curtailment of possible damage through missile defense systems mainly makes sense for the task of destroying the means of nuclear attack of likely adversaries by resorting to a preemptive strike [4].

The threat of a nuclear missile attack by non-state actors and rogue states, initially declared by Washington to justify its own mammoth plans, never held water. Meanwhile, the level of missile technology and unmanned vehicles in countries such as North Korea and Iran has significantly advanced since the early 2000s. The United States undoubtedly minds this dynamic in its own military construction. As for the use of ballistic missiles by non-state actors, even given the Middle East experience, Washington clearly exaggerates the level of danger. In order to protect U.S. military infrastructure in the Persian Gulf, for example, an approach based on covering critical facilities and part of a potential theater of war is justified.

The 2010 Ballistic Missile Defense Review Report outlines a course to maximize globalization of activities through involving new states to establish regional and local components in potential theaters of war and areas of strategic interest, as well as to cut the costs. The document describes an adaptive approach to improving missile defense capabilities, based on fixed land-based, sea-based, and mobile land-based components. Back in 2012, a number of U.S. policymakers mentioned the Pentagon’s desire to create a broad regional missile defense infrastructure in Asia Pacific to meet the country’s unique nuclear deterrence needs [5]. Notably, no country of East Asia, in whole or in part, has ever expressed its intentions to unprovokedly attack American bases, much less the territory of the United States. Pyongyang’s statements about “striking a crushing blow to the capital of the enemy” stand somewhat apart. However, the North Korean leadership still minds the policy chosen by the United States and the Republic of Korea to confront the DPRK militarily.

The U.S. Missile Defense Agency has requested USD 28.9 billion for 2024, of which USD 9.2 billion is earmarked directly for the purchase of weapons systems. The Congressional Research Service document names the ballistic missile development programs of North Korea and Iran among the main threats to national security, along with the ability of Chinese medium-range missiles to hit U.S. bases, warships in East Asia and the high concentration of destruction capacity in the area of the Taiwan Strait, as well as Russia’s alleged deployment of missile weapons with an intermediate range of 3,500 to 5,500 km. In the opinion of some U.S. experts, funding should be significantly increased, and certain measures to improve the survivability of the SNF should be taken.

Is air defense needed in East Asia?

The U.S. global missile defense architecture is gradually built around nodal components, some of which cover East Asia. The Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMWS) is based on radar systems and a satellite constellation. Within the Pacific in particular, fixed stations are deployed in California and the Aleutian Islands, while mobile radars on floating platforms are deployed in the Marshall Islands and bases in Japan.

Since 2004, the United States has deployed 44 GBI (ground-based interceptor) missiles at Fort Greely (Alaska) and Vandenberg (California) air bases as part of the Ground-based Midcourse Defense program. For all that, in a series of 18 tests between 1999 and 2018 (i.e. the first took place even before Washington officially withdrew from the ABM Treaty), eight failed. The product is based on the Minuteman ICBM with boosters, capable of reaching the speeds of over 8 km/sec and intercepting targets at a range of up to 4,000 km and an altitude of 2,000 km [6]. Notably, Lockheed-Martin was awarded a USD 17 billion contract in 2024 to develop the Next Generation Interceptor by 2028.

From 1995 to 2018, more than 20 tests of the THAAD (Terminal high altitude area defense) missile defense system were conducted. The interceptor missile is capable of destroying warheads with a kinetic strike at a range of up to 200 kilometers and an altitude of up to 150 kilometers on its final trajectory. The U.S. military has seven batteries, of which two are already deployed on the island of Guam and in the Republic of Korea. Due to its mobility, the system can be quickly airlifted from the mainland to a threatened area. Pinpoint missile defense is carried out by Patriot PAC-3 systems, which, in addition to airborne targets, are capable of hitting ballistic targets at an altitude of 20 km and a range of about 50 km, i.e. directly above the protected target.

The highest density of missile defense can be provided by sea-based systems on warships with the Aegis BMDS. The characteristics of the latest modifications of the SM-3 Block IIa interceptors provide the capability of destroying various classes and types of missiles as well as low-orbit satellites at a range of more than 2,000 km and an altitude of more than 250 km. The results of tests conducted from 1999 to 2018 are noteworthy: 40 successful launches out of 49. By the end of 2025, the number of destroyers and cruisers equipped with guided anti-missile projectiles in the US Navy is expected to increase to 56 battle ships. As estimated by the US Naval Institute (USNI), the total number of SM-3 interceptors of different versions is 265 with more than a thousand SM-6 interceptors for destroying targets in the atmosphere at a distance of up to 370 km. The U.S. Navy’s 7th Fleet alone, based mostly in Japan, includes nine ships capable of performing missile defense missions.

The system developed in Japan over the past 20 years features a high degree of collaboration with the United States. The Maritime Self-Defense Force already has six guided missile destroyers with SM-3 anti-missiles, as well as more than 24 Patriot-3 batteries. Notably, Tokyo has already repeatedly deployed PAC-3 launchers on the outer islands of Okinawa Prefecture, allegedly as a response to DPRK missile tests. The Japanese leadership never ruled out the acquisition of THAAD systems, but the final decision has not yet been made, especially since the Americans may well deploy their own battery on Okinawa if necessary. In 2020, Japan refused to build an Aegis Ashore system on its territory, similar to those on duty in Poland and Romania.

The Republic of Korea has three Aegis BMDS destroyers equipped with interceptors (mostly SM-6). Seoul is also building an echeloned KAMD (Korean Air and Missile Defense) network largely based on the Patriots, harnessing the Israeli experience with the Iron Dome. There is an opinion [7] that the U.S. THAAD battery will fail to react to a missile launch from North Korea because it is too close, and South Korean ships will have to be moved as far away as Okinawa for the reliable interception of North-Korean missiles. This makes one think that the ROK’s capabilities are more useful in terms of protecting U.S. military facilities in the Indian Pacific Region and the U.S. territory. Australia also contributes to U.S. missile defense with its three Hobart-class destroyers capable of using the SM-6, the SBIRS infrared satellite reconnaissance system, and the JORN over-the-horizon radar.

* * *

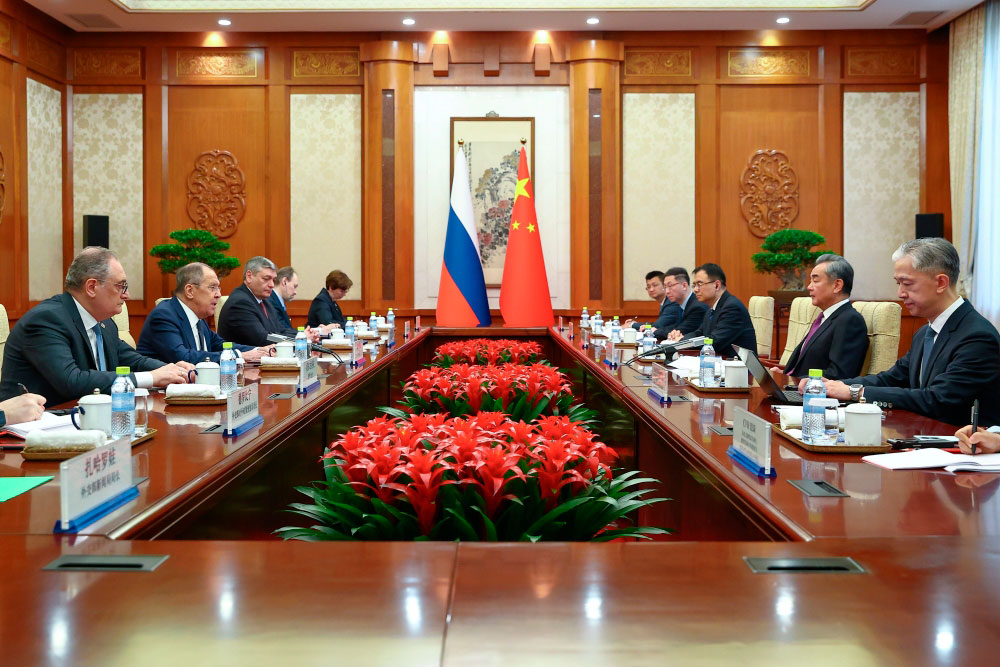

Almost 17 years ago, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov pointed out that the intensive deployment of the theater missile defense system in the Asia Pacific calls global strategic stability into question, because it could be used against Russia and China. In 2018, the head of Russian diplomacy insistently urged Japan to enter into a dialogue about the U.S. plans to create a global missile defense system to prevent violation of Russia’s interests, in accordance with the principle of indivisible security. However, none has seen fit to respond to Russia’s well-grounded concerns and ensure the East Asia regional security sustainability. Under these circumstances, Moscow and Beijing’s increased focus on building up their own defense capabilities against a missile attack, particularly on cooperation in creating a unified ballistic missile defense system, can be considered quite justified.

1. Gelovani V.A., Piontkovskiy A.A. Evolution of Strategic Stability Concepts. – M.: LKI, 2008 – 112 pages, p. 6

2. Frykland R. 100 million lives: maximum survival in a nuclear war. – New York.: MacMillan, 175 p.

3. Konyshev V., Sergunin A., Shatskaya V. The US Missile Defense System: the Past, the Present, and the Future. – SPb: Aurora, 2015, 168 pages, p. 28

4. Ivanov O.P. Military Force in the US Global Strategy. M.: Vostok-Zapad, 2008, p. 115

5. Kozin V.P. The Evolution of US Missile Defense and Russia’s Stance. M.: RISI. – 2013. – 384 pages, p. 179 Konyshev V. ibid, p. 54

6. Ibid, p. 116