Beyond the Conflict in Ukraine: Towards New European Security Architecture

(votes: 2, rating: 4.5) |

(2 votes) |

Ph.D. in History, Academic Director of the Russian International Affairs Council, RIAC Member

At the current stage of the ongoing military conflict between Russia and Ukraine any attempts to proceed in the direction of a new European security architecture would be at best premature, if not completely preposterous. The immediate European security priorities have shifted from promoting an inclusive and comprehensive Euro-Atlantic security system to avoiding a direct Russia-NATO military confrontation and to preventing the military hostilities from climbing to the level of a nuclear war. The rest of the traditional European security agenda is put on a back burner for the time being. One can only hope that this agenda will return to the table before too long, and that the previous experience of managing the East-West stalemate in the shared European neighborhood will be in demand once again. It is evident that the outcome of the crisis—no matter what it can mean in practical terms—will have a profound impact on the new security arrangements that might or might not emerge within the Euro-Atlantic space in the years to come.

These arrangements should reflect a new balance of power between major players not only in Europe itself, but also at the global level and, as some Russian experts argue, fine-tuning such a balance may take up to ten years. If this assumption is right, Europe will remain in a strategic limbo for a long time with very limited opportunities to solve its systemic security problems.

The future of the European strategic autonomy is often perceived in Moscow as one of the most important independent variables defining not only the likely future of the European security architecture but the future of the emerging world order at large. If the contemporary Western cohesion turns out to be tactical, confined mostly to the crisis around Ukraine and ultimately short-lived, then the world will rapidly move to a new multipolar (polycentric) system in which the United States and the European Union will constitute two different centres of power.

However, if a newly acquired Western unity happens to be strategic, long-term, and going far beyond a specific crisis in Europe, then the concept of a mature multipolarity has to be put on hold, and the international system is likely to be shaped amid the clash between the West and the Rest. The most recent Declaration on cooperation signed by NATO and EU in early 2023 points in the second direction, but it still remains to be seen to what extent the stated intentions of the Declaration are going to be translated into specific actions beyond Ukraine.

Can Europe be reunited once again? That remains to be seen, but this is definitely not going to happen any time soon. It might take another generation in Russia and in the West to overcome the repercussions of the ongoing conflict and to restart the process that they launched together almost forty years ago. Be mindful, that the staring positions even in ten or twenty years from now are likely to be inferior to the situation of the late 1980s: forty years ago, both sides were ready to give each other the benefit of the doubt and to entertain a romantic vision of united Europe, while even in many years from now the memories of the failed attempt to build a common European security space are likely to feed skepticism and doubts about whether uniting Europe is possible in principle.

One could also imagine that most of the new long-term security arrangements in Europe will emerge as organic components of a much larger Eurasian security system that will ultimately make Europe geographically extended to include the vast Eurasian land mass. Already now, there is an ongoing process of fusion between previously separate European and the global security agendas. Leaders of Japan, Republic of Korea, Australia, and New Zealand take part in recent NATO summits, the alliance is more and more positioning itself as a global rather than a regional defense partnership. At the same time, Russia and China conduct joint naval exercises in the Mediterranean and in the Baltic Seas, Moscow upgrades its security cooperation with African nations that might have a direct impact on the European security.

Nothing suggests that this trend might stop anytime soon. If it continues, the European security agenda might become a hostage to the developments taking place in other regions of the world—like East Asia or Middle East and Noth Africa. The indivisible security approach will be the only solution to European security problems even if it turns out to be extremely hard to reach.

At the current stage of the ongoing military conflict between Russia and Ukraine any attempts to proceed in the direction of a new European security architecture would be at best premature, if not completely preposterous. The immediate European security priorities have shifted from promoting an inclusive and comprehensive Euro-Atlantic security system to avoiding a direct Russia-NATO military confrontation and to preventing the military hostilities from climbing to the level of a nuclear war [1]. The rest of the traditional European security agenda is put on a back burner for the time being. One can only hope that this agenda will return to the table before too long, and that the previous experience of managing the East-West stalemate in the shared European neighborhood will be in demand once again.

A lot will depend on when and how exactly the conflict ends, which is hard to predict at this point in time. Regretfully, today even a ceasefire, an armistice or meaningful de-escalation measures look almost unattainable, and things on the ground might get even worse before they get any better. However, it is evident that the outcome of the crisis—no matter what it can mean in practical terms—will have a profound impact on the new security arrangements that might or might not emerge within the Euro-Atlantic space in the years to come.

These arrangements should reflect a new balance of power between major players not only in Europe itself, but also at the global level and, as some Russian experts argue, fine-tuning such a balance may take up to ten years [2]. If this assumption is right, Europe will remain in a strategic limbo for a long time with very limited opportunities to solve its systemic security problems.

Europe in the 2023 Russia’s Foreign Policy Concept

Hybrid War and Hybrid Peace

Still, even keeping all the evident uncertainties in mind, it would make sense to take a look at the interpretation, albeit general and provisional, currently put on of a new European order by Russian officials and influential analysts. Throughout 2022-2023 one there were active, sometimes very emotional, and politically biased discussions of this very important issue. All the ambiguities notwithstanding, some of the long-term trends of European developments are apparent to every impartial observer. For instance, in the framework of the transatlantic relations, the United States is getting stronger, while Europe is getting weaker. NATO is gaining in relative power, and the European Union is putting its strategic autonomy ambitions on hold. Within the EU the balance of power between New Europe and Old Europe is shifting in favor of the former and to the detriment of the latter [3].

Arguably, the most important contemporary official document addressing the emerging European security agenda is a new Russia’s Foreign Policy Concept released in March 2023 [4]. It is worth noting that the first draft of the new Concept was prepared back in 2021 [5], but the launch of the Special Military Operation in Ukraine and the subsequent dramatic deterioration of Russia’s relations with the West necessitated significant changes to the document and additional appropriate interdepartmental consultations that postponed its release by at least one year.

Russia’s officials attach a lot of importance to the Concept often presenting it as a consensus paper reflecting positions of various groups in the country’s leadership. The previous version of the Concept was adopted in late November 2016 [6], which suggests that a new document is supposed to have a relatively long life. If nothing dramatic happens within the country’s political system, the new Concept may well serve the Russia’s leadership till the end of 2020s.

The new Concept is predictably very critical of the European countries, directly accusing most of them of pursuing “an aggressive policy towards Russia aimed at creating threats to the security and sovereignty of the Russian Federation, gaining unilateral economic advantages, undermining domestic political stability and eroding traditional Russian spiritual and moral values, and creating obstacles to Russia’s cooperation with allies and partners” [7]. Not surprisingly, the West is held solely responsible for such a dire state of its relations with Moscow, and it is therefore up to the West to change the status quo by rejecting its anti-Russian course including its interference into Russia’s internal affairs and by moving on to a long-term policy of good-neighborliness and mutually beneficial cooperation with Russia. Until such a change takes place, there will be no common European security architecture and Europe will remain divided or split into the West and the East.

“…Objective prerequisites for the formation of a new model of coexistence with European states are geographical proximity, historically developed deep cultural, humanitarian, and economic ties of the peoples and states of the European part of Eurasia. The main factor complicating the normalization of relations between Russia and European states is the strategic course of the USA and their individual allies to draw and deepen dividing lines in the European region in order to weaken and undermine the competitiveness of the economies of Russia and European states, as wellas to limit the sovereignty of European states andensure US global domination… The realization by the states of Europe that there is no alternative to peaceful coexistence and mutually beneficial equal cooperation with Russia, an increase in the level of their foreign policy independence and a transition to a policy of good-neighborliness with the Russian Federation will have a positive effect on the security and welfare of the European region and help European states take their proper place in the Greater Eurasian Partnership and in a multipolar world…”.

2023 Russian Foreign Policy Concept

Source: Russian Foreign Ministry

However, beyond this strident rhetoric of the Concept one can find in it some hints suggesting more nuanced and calibrated positions. For instance, (continental) Europe is treated separately from the United States and other Anglo-Saxon states. While the latter is regarded as the main cause of continuous Russia-West confrontation, the former are reprehended mostly for their alleged inability or unwillingness to resist the US pressure and to stand up against the American hegemony [8].

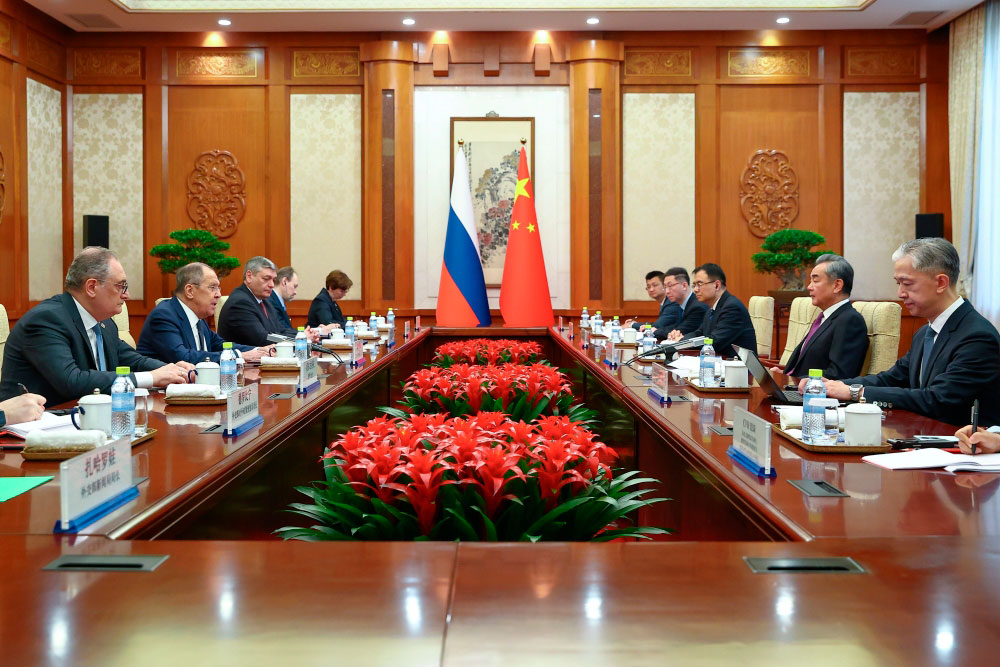

“We have never said no to an equal dialogue with our European partners, or to looking for ways to resolve security issues. We remain hopeful that sooner or later we will see political forces in Europe that are guided by their own national interests rather than a desire to curry favor with someone sitting on the other side of the ocean. Then we will have someone to sit down and talk with”.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov

January 30, 2023

Source: Russian Foreign Ministry

Russian leadership looks forward to forthcoming political changes in Europe that would make major European nations more open to a productive dialogue with Moscow. Such changes might be triggered by mounting economic and social problems, the shift of public opinion on the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, a new migration crisis, a rise of the rightist populism, a new Republican administration in the White House or by some other social, political and economic black swans emerging either inside Europe or in the global system of international relations.

Debating the European strategic autonomy

The International System between Crisis and Revolution

The future of the European strategic autonomy is often perceived in Moscow as one of the most important independent variables defining not only the likely future of the European security architecture [9] but the future of the emerging world order at large. If the contemporary Western cohesion turns out to be tactical, confined mostly to the crisis around Ukraine and ultimately short-lived, then the world will rapidly move to a new multipolar (polycentric) system in which the United States and the European Union will constitute two different centres of power.

However, if a newly acquired Western unity happens to be strategic, long-term, and going far beyond a specific crisis in Europe, then the concept of a mature multipolarity has to be put on hold, and the international system is likely to be shaped amid the clash between the West and the Rest. The most recent Declaration on cooperation signed by NATO and EU in early 2023 points in the second direction [10], but it still remains to be seen to what extent the stated intentions of the Declaration are going to be translated into specific actions beyond Ukraine.

December 1991 — Russia joined the North Atlantic Cooperation Council.

June 1994 — Russia joined the Partnership for Peace (PfP) program.

May 1997 — NATO-Russia Founding Act was signed.

March 1998 — Russian Permanent Mission to NATO was established.

September 2000 — NATO Information Office in Moscow was opened.

May 2002 — Russia-NATO Council was established.

April 2008 — NATO Bucharest summit was held. NATO proclaimed that Ukraine and Georgia would become NATO members.

August 2008 — Russia’s peace enforcement operation within Georgian-South Ossetian conflict took place. Russia-NATO Council meetings and implementation of joint programs were suspended.

July 2016 — NATO Warsaw summit was held. Russia was named as the main threat to NATO.

October-November 2021 — Russian diplomats were expelled from Russian Mission to NATO. In response Russia suspended its Mission to NATO and ordered to close NATO office in Moscow.

December 2021-January 2022 — Russia put forward a draft treaty between the Russian Federation and the United States of America on security guarantees and an agreement on measures to ensure the security of the Russian Federation and member states of NATO. NATO rejected them.

Source: NATO

Likewise, the attitudes in the Kremlin towards various European and Transatlantic institutions are not identical—they are explicitly negative in cases of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the European Union and the Council of Europe, while they are generally positive, some reservations notwithstanding, in case of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Throughout 2022–2023 many analysts predicted that Russia would soon terminate its membership of OSCE—especially after Sergey Lavrov had been denied the participation in the OSCE Ministerial Council in December of 2022 by the Polish chair of the Organization, but such a termination has never happened. Still, there is a lot of skepticism in Moscow regarding the likely future of OSCE, and the expectations of the role it can play in rebuilding the European security are not too high [11].

The list of Russia’s demands to the West has not changed a lot since the beginning of the Special Military Operation—at least, in the official narrative. In December 2022, Sergey Lavrov reminded his Western counterparts that the only way to restore a meaningful dialogue between Russia and the West would be to get back to Moscow’s proposals that had been made public at the end of 2021 [12]. The draft Russia-US [13] and Russia-NATO [14] agreements released in December 2021 called for a complete reversal of major security decisions made by Washington and its European allies since 1997 including the deployment of the NATO military infrastructure in former Warsaw Pact Organization member states and in former Soviet Republics, not to mention a legally binding NATO commitment not to expand NATO eastward.

Clear enough, this position has no chances of being accepted by the United States or its European allies, even if Russia wins on the battlefield. On the contrary, the current crisis has triggered yet further NATO’s enlargement and new deployments of the alliance infrastructure on its Eastern flank. The deep gap in Russian and Western visions of the desirable European future rules out any joint practical plans to move towards a common European or Euro-Atlantic security space. Though Ukraine remains the central piece of the East-West disagreements, they are not limited to Ukraine only. As Minister Sergey Lavrov pointed out in one of his recent interviews, “our country will not enter any geopolitical or geoeconomic constructions, in which we have no capacities to protect our interests” [15]. Russia’s foreign policy center of gravity is moving towards the East and to the South, while the West is rapidly losing its position as the top Moscow’s foreign policy priority.

Getting back to the Cold War order

Russia-West: Rising Stakes

Many influential Russian analysts argue that under the current challenging circumstances the best possible scenario for the European security would be to move back to the old Cold War system, even though many practical arrangements are likely to differ greatly from what was in place during the four decades of the Cold War. Indeed, all its shortcomings and deficiencies notwithstanding, the Cold War system, especially in the 1970s and 1980s, provided for a certain degree of clarity, predictability and even trust between the East and the West of Europe, which the rapidly disintegrating European security space cannot claim today. However, it remains unclear whether the Cold War model in general, even properly modified, and approximated, will be able to serve Europe well after the Ukrainian crisis is over.

So far, Russia has responded to the changing geostrategic environment by enhancing its military capabilities in the European theater. One should mention restructuring of Russia’s military districts, creating new armies and increasing the size of the Armed Forces in general [16]. More emphasis is put on further modernizing national strategic forces. On top of that, the Kremlin announced its decision to deploy tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus and to provide for a nuclear sharing arrangement with Minsk. Though these measures cannot be considered insignificant or purely symbolic, they do not bring the East-West clash exactly to where it was 50 or 60 years ago.

From its side, NATO has decided to go for a rather limited increase of its military presence on the Eastern flank [17]. An increase from four battalions stationed there on the rotation basis to eight battalions or even to eight brigades is not likely to be a dramatic game-changer for the security dynamics in Europe. However, many European nations, especially those in Central Europe, would like to go much further—in their own defense efforts as well as in deploying other alliance forces (including even nuclear weapons) on their national soil. If these aspirations turn into a new European security normal, the task of fine-tuning a new military balance on the continent is likely to become much more complicated.

No matter how the Russian-Ukrainian conflict ends and what additional measures the NATO alliance might take on its Eastern flank in the years to come, the new security landscape in Europe will be characterized by new challenges posed by a higher density of forward stationed armed forces in Central and Eastern Europe, as well as by a more intense sea and air military traffic in already quite condensed sea and air spaces. One should also mention a likely increase in scale and frequency of military exercises on both sides in close geographic proximity to each other. These trends inevitably raise the likelihood of accidents and military incidents, containing multiple risks of an inadvertent escalation including the escalation into a big European war—conventional or even nuclear.

A graphic illustration of this worrisome trend is the recent decision of NATO to conduct in 2024 the Steadfast Defender military exercises, which were considered to be the largest ones since the end of the Cold War, engaging more than 40 thousand troops, and some 50+ military vessels [18]. It is easy to predict that such NATO’s move will motivate Russia to proceed with its own large-scale exercises plans along the contact line with the alliance forces [19]. One of the most disturbing developments in the new discourse on security dilemmas in Europe is the growing acceptance by at least a part of the Russian expert community of the idea of a possible use of tactical nuclear weapons at some stage of the current conflict.

However, like it was the case during the Cold War, current division of Europe does not mean that there are no common or overlapping interests pursued by the East and the West, by Russia and NATO, or Russia and the European Union. The most evident convergence of interests is in reducing risks of an uncontrolled escalation and the likely costs of the continuous political and military confrontation. In other words, both sides need, firstly, crisis stability mechanisms and, secondly, arms race stability mechanisms—even more so, if they cannot rule out future crises or a rampant arms race in and around Europe. 2023 Russia’s Foreign Policy Concept implicitly supports this view by making a case for a new model of coexistence between Russia and the West stating that “objective prerequisites for the formation of a new model of coexistence with European states are geographical proximity, historically developed deep cultural, humanitarian and economic ties of the peoples and states of the European part of Eurasia” [20].

The idea of a future coexistence is not presented in any detail in the text of the Concept, one can only guess what it may mean and what it will mean in practice. In any case, it terminologically echoes the old Soviet notion of peaceful coexistence of two socio-economic systems. Though Russia today is no longer a communist state, the reemergence of coexistence implies that the profound gap in perceptions, narratives, interests and, above all, in values between the East and the West is as real as it was some fifty years ago and, moreover, that it will remain in place for a long time.

One should keep in mind that the notion of Russia’s values different from the values of the West remains vague and ambiguous; for example, the current Russia’s Constitution of 1993 modeled to a large degree on the Fundamental Laws of major Western countries with their strong emphasis on representative democracy, checks and balances, individual human rights, and so on. In terms of its social structure, middle class lifestyles, in terms of education and urbanization levels Russia today is much closer to her Western neighbors than to the nations of the Global South. The popular concept of Russia as state-civilization remains rather general and arguably declaratory [21], it requires a lot of conceptual elaboration in order to avoid defining Russia exclusively through its political opposition to the West in general or to Europe in particular [22]. At this stage it is hard to predict whether the East-West gap in values will remain mostly at the level of rhetoric, or it will start to increasingly affect state and political institutions, economic mechanisms, and social trends in Russia.

Putting this fundamental question aside, in order to narrow a more specific gap between Russia and the West in security domain the first logical step to make should be in restoring the lines of communication that are now broken or frozen. Beyond putting an end to the ongoing diplomatic war and bringing the embassies on both sides back to the normal mode of operation, it is important to get the two sides reengaged into diverse military-to-military contacts, including not only at the top level, but also at various operational levels. It is worth reminding that the operational military dimension of the NATO-Russia Council (NRC) ceased to exist already in 2014, when the NATO side concluded that its continuation would indicate the alleged willingness of the West to go on with business as usual and to de facto accept the changed legal status of the Crimean Peninsula. That decision was criticized in Russia on the grounds that communications should not be regarded as a favor that one side can grant the other or take it back as a signal of resentment or disappointment.

Confidence- and security-building measures (CSBMs) as the first step

Don’t Trust and Don’t Verify. New Normality for New START

Once the communication lines are back in place, the sides could proceed with various confidence-building measures to provide for more transparency and predictability of their respective military activities, plans, and defense postures. Maybe, with political will demonstrated by Moscow and Western capitals, some of already time-tested multilateral mechanisms that are now dormant or frozen, like the Vienna Document or the Open Skies Treaty, could be reanimated in a revised and modernized format. Another, less known, but nevertheless quite important multilateral accomplishment deserving attention is the Cooperative Airspace Initiative (CAI) set up by a NATO-Russia working group in 2002 in response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the US.

The CAI was intended to provide an enhanced transparency, early notification of suspicious air activities (including loss of communications), and rapid coordination and joint responses to security incidents in European airspace [23]. Another document also worth mentioning is the 2017 agreement between Russia and NATO on the use of transponders during military flights over the Baltic Sea; it was negotiated within a project group, operating under the aegis of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO).

It is clear, however, that to get back to even the most incremental and technical multilateral agreements would be extremely difficult—at least, in the immediate future. One can argue that any multilateral arrangement based on consensus among many parties in Europe these days remains unrealistic. For example, OSCE includes 57 member states representing three continents with the total population of more than a billion people. The NATO alliance is also a diverse group of nations, and every one of them might in theory veto any potential agreement with Russia, even a technical one.

We should not also forget that along with a number of success stories of multilateral CSBMs in Europe and beyond it, this format has also had downright failures. For instance, for a long time Russia and NATO had been struggling over the issue of observers to military exercises, especially snap exercises. No compromise solution was reached, partially due to the termination of operational mil-to-mil communication within the framework of the Russia-NATO Council. Though this problem could be revisited once the two sides get back to the negotiating table, the odds are that in a more challenging geostrategic environment it would be even more difficult to find a satisfactory solution to it [24].

At the same time, there is a wide range of bilateral agreements, mostly between Moscow and Washington, which can be used as a foundation for building something more ambitious. Above all, it is the 1972 US-Soviet Agreement on Incidents at Sea and in the Airspace Above the Sea (INCSEA). There are similar agreements between Russia and a number of other NATO member states (Canada, France, Greece, Germany, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, Türkiye, UK) though, unfortunately, not with most of the countries that are in geographical proximity to Russia in the Baltic Sea (Baltic states and Poland) or in the Black Sea area (Bulgaria, Romania). The usefulness of INCSEAs has been tested in many cases, and their further extension to other NATO member states would make a lot of sense, even though current political realities in the majority of East and Central European states make such arrangements hard to sell domestically.

Another interesting example is the 1989 US-Soviet Agreement on the Prevention of Dangerous Military Activities (DMA), which requires troops to behave with caution in the border area. The two sides also have a successful experience of the US-Russia post-conflict settlement mechanism in Syria launched in the fall of 2015. This format might be of particular value today and tomorrow, since it provides for discreet professional military engagement below the political radar screen. We can easily imagine similar low-profile arrangements covering other explosive areas of the world, including those in Europe.

Needless to say, most of the US-Soviet CSBMs agreed upon long time ago, would need significant modernization. This will not be easy, even if the political will and professional commitment are there. For instance, the INCSEAs in question were supposed to help prevent collisions of manned aircraft. However, these days the skies in conflict areas are packed with lots of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Naturally, back in 1972 or in 1989 nobody could have envisaged the emergence of UAVs. Efficient communication between two UAVs operators, who might be located in two remote corners of the world, stands out as a real challenge.

Though bilateral agreements—formal or informal—might be easier to reach than similar multilateral ones, the former have their own limitations. In particular, any future agreements should somehow consider the emerging trend in the West to rely more and more on multilateral forces rather than on forces of an individual alliance member. This defense multilateralization inevitably leads to multilateralization of all future CSBMs as well. Likewise, an accelerating process of the Russia-Belarus security integration might necessitate the engagement of both Moscow and Minsk into various specific CSBMs along the line of contact with NATO [25]. In some cases, there seems to be no viable alternative to a multilateral NATO-Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) type interaction though many experts at both NATO and the CSTO might find it politically easier to try working through more inclusive OSCE mechanisms [26].

Dim prospects for conventional arms control

In terms of the format, it seems that at this juncture any legally binding bilateral CSBMs arrangements between Russia and individual NATO member states would be almost as hard to conclude as similar multilateral agreements between Russia and NATO at large. At the same time, since there is no trust between the two sides, any informal arrangements would be subject to criticism and opposition in Moscow and in Westen capitals. In fact, Russia now insists on a very legalistic approach in its relations with the West in general arguing that the United States and its allies on many occasions violated informal agreements and commitments that they had reached earlier.

This dilemma might complicate the correlation between CSBMs and arms control in Europe. It would be tempting to suggest that a new European arms control regime should develop by itself on the basis of efficient CSBMs that will gradually build predictability and trust between opposing sides. However, this logic is now challenged by some experts, who argue that arms control usually goes hand in hand with intrusive verification mechanisms attached, while CSBMs, as a rule, are not accompanied by such mechanisms. If this is the case, then the slow movement towards new CSBMs and towards a new arms control should be simultaneous rather than sequential.

In some longer-term perspective, a divided Europe security architecture, at least, in theory, might even go as far as to include something like CFE-2—an all-European legally binding agreement that could set limits on particular types of weapons deployed in particular territories across the European continent. These days, it is popular to refer to numerous imperfections and even deficiencies of the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE Treaty) signed in 1990. Of course, the initial version of the treaty became obsolete very soon—right after the disintegration of the Soviet block and the Soviet Union itself. However, it is impossible to deny the fact that after 1990 Europe witnessed dramatic reductions of military arsenals and forces deployed by the participants; most of the credit for monitoring this process should go to OSCE rather than to any bilateral Russia-NATO consultative mechanisms. Russian leadership fully recognizes that the absence of CFE Treaty creates a vacuum in the European security agenda that has to be filled sooner or later with new legal arrangements [27].

Of course, any new arrangement should be very different from the original CFE Treaty signed more than thirty-three years ago. Even the Adapted CFE Treaty approved in 1999 at the OSCE Summit in Istanbul looks more than antiquated [28]. Russia suspended its participation in the CFE Treaty in 2007—long before the conflict in Ukraine erupted in 2022 and even before the crises over Crimea (2014) and in the South Caucasus (2008). This implies that even if the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine is somehow resolved, its resolution is not likely to incentivize Moscow to enter anything like the original CFE Treaty of 1990 or the Adapted CFE Treaty of 1999. One can imagine that Russia might be tempted to pursue a policy of defense isolationism abstaining from accepting any rigid limits on its armed forces stationed in Europe.

“…In particular, the provision by it of information and the acceptance and conduct of inspections are brought to a halt. During the suspension period, Russia will not be bound by restrictions, including flank restrictions, on the number of its conventional weapons. At the same time, we have no plans for their massive build-up or concentration on the borders with neighbors in the present circumstances. Later on, the real quantities and stationing of weapons and equipment will depend on a concrete military-political situation, particularly the readiness of our partners to show restraint.

This move was due to the exceptional circumstances pertaining to the content of the CFE Treaty affecting the security of Russia and requiring some immediate measures. Of them we had repeatedly and thoroughly told our treaty partners.

The Treaty, signed during the Cold War, has long since ceased to meet contemporary European realities and our security interests. Its adapted version has been unable to enter into force for eight years now because of the position of the NATO countries tying its ratification to the fulfillment by Russia of farfetched requirements having nothing to do with the CFE Treaty. Moreover, they undertook a number of steps incompatible with the letter and spirit of the Treaty and undermining the balances that lie at its core. Russia’s continued compliance with the Treaty in such a situation of legal uncertainty would put in jeopardy its national interests in the sphere of military security.

The suspension is not an aim in itself, but a means of endeavor by the Russian Federation to restore the viability of the conventional arms control regime in Europe, to which we see no reasonable alternative. This move is politically justified, well-grounded from the legal point of view and makes it possible, given the political will of Russia’s partners, within a fairly short space of time to resume the operation of the CFE Treaty by a decision of the President of the Russian Federation…”.

Statement by Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs Regarding Suspension by Russian

Federation of Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFETreaty)

December 12, 2007

Source: Russian Foreign Ministry

Likewise, a new set of incentives has to be offered to the countries in Central and Eastern Europe, above all—to Poland, Romania and the Baltic states (the latter never participated in either original CFE Treaty or the Adapted CFE Treaty). It is easy to predict that a deep distrust in Moscow will remain in Warsaw, Bucharest and in Vilnius long after the conflict in Ukraine is over. To overcome the opposition to any arms control deals with Russia along the line of contact will be a challenging task. Finally, there should be ways to incorporate into such a deal new types of weapons like cruise missiles or drones, to factor in emerging and disruptive technologies as well as a more general geopolitical environment (e.g., a more active role of China in European affairs).

Even more important difference between the original CFE Treaty and any future conventional arms control agreements in Europe is that back in 1990 there still was a rough parity between the West and the East of Europe. Today such a parity is no longer in place, and it is not likely to reemerge in any foreseeable future. Suffice it to say that back in 1990 NATO had 16 member states, while by summer 2023 this number had grown to 31 and reached 32 when Sweden finally joined the alliance in 2024. Can these asymmetries be incorporated into a new agreement? Will the negotiators be able to define the levels of reasonable sufficiency for each of participating states? What, if anything, can be done about the increased mobility or about the increased firepower of forces on both sides?

One of the options would be to lay the focus in new agreements not so much on any quantitative ceilings applied to particular types of weapons, but rather on the maximum transparency of armed forces of the participating states, including troops and weapons deployments, military exercises, modernization programs, defense doctrines and so on. In this case, the red line between CSBMs and arms control will gradually erode—both tracks will merge in a more comprehensive and more multi-faceted format of arms management based on a complex mixture of unilateral, bilateral, minilateral and multilateral arrangements.

Nuclear matters and other complications

Eurasian Security Structure: From Idea to Practice

The ambiguous relationship between the conventional and the nuclear dimension of European security is likely to remain one of the major complicating factors for any future arrangements in Europe. The United States has announced a new concept of integrated deterrence [29], which is often interpreted as a long-term commitment to mix conventional and nuclear means with a special emphasis on the cutting-edge non-nuclear capabilities like conventionally armed hypersonic missiles, space and cyberspace tools that should help the US retain its advantage and, I quote, across every domain. This change, but in the opposite direction, might take place on the Russian side. If Moscow concludes that it is no longer in a position to maintain robust conventional deterrence in Europe, it might be tempted to rely more heavily on tactical nuclear weapons blurring the red line between nuclear and conventional dimensions of deterrence. This trend, if it continues, might put into question traditional approaches to arms control in Europe, which earlier implied a clear separation of its nuclear and non-nuclear dimensions.

In his Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly in 2023, President Vladimir Putin commented on Kremlin’s decision to suspend Russia’s participation in the New START Treaty with the United States. One of the preconditions for resuming US-Russian strategic arms control mechanism he referred to was to bring into the equation the combined NATO’s striking power, i.e., nuclear capabilities of the United Kingdom and France [30]. Given the well-known long-standing US, British and French opposition to this idea, it can be concluded that the resumption of a full-fledged strategic dialogue between Moscow and Washington is not likely to happen anytime soon. The United States, in its turn, is raising more and more concerns about the growing Chinese nuclear capabilities; any attempt to factor China into the US-Russian strategic arms control equation would immensely complicate any dialogue between Washington and Moscow.

There are at least two other additional complicating factors, which are directly related to Europe. First, the United States insists on addressing the issue of Russia’s tactical nuclear weapons deployed in the European part of its territory (one can suspect that from now on Washington will also raise the question of Russian nuclear weapons stationed in Belarus). Second, Russia will continue to press the case of the US missile defense systems deployed in Romania and in Poland that might have another complicating impact on the European stability and on the US-Russia strategic balance.

However, all these obstacles and complications do not necessarily mean that the two sides cannot go for some unilateral but coordinated actions demonstrating their intention to avoid an uncontrolled nuclear arms race. In the European context this might mean, for example, that both Russia and the United States might decide to respect the limitations set by the 1987 US-Soviet Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty) though both sides formally terminated their participation in the agreement in 2019. According to Russian officials, the prolongation of the unilateral moratorium on the deployment of middle-range missiles in Europe announced by Moscow back in 2019 will depend on the reciprocity to be demonstrated by the United States [31]. The Biden administration (2021-present time) at some point expressed its interest in discussing this matter within the framework of the US-Russian strategic stability consultations launched in 2021, but these consultations were frozen after Russia had launched its Special Military Operation in Ukraine in February 2022.

The uncertain future of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) is yet another factor that might have a detrimental impact on the security situation in Europe. The United States signed CTBT and abided by its provisions, but never ratified it, which was one of the reasons for CTBT to not enter into force. Russia did sign and ratify the CTBT, but Moscow decided to recall the ratification as a mirror response to the US position [32][33]. If the US and Russia resume their nuclear tests even far away from the European continent, the negative impact of these moves on the overall European security landscape will be more than substantial.

A separate set of arrangements will be needed to deal with security problems in the most unstable and potentially explosive European subregions. In particular, that may include the Black Sea, the Baltic Sea and the Arctic. Each of these subregions has its own set of unique features and deserves a specific approach. Not all of the subregional security problems in Europe should be looked at through the lens of the Russia-West confrontation. One can refer to security challenges in the Western Balkans or in the South Caucasus that have deep indigenous roots and are likely to remain in place even if the East-West dimension of the European security agenda is somehow resolved or defused.

Yet, another challenge to be addressed is the growing number of nonconventional threats to security in Europe. It includes such dimensions as climate change, illegal migrations, international terrorism, cybercrime, and many others. Potential cooperation in these fields might emerge in the bottom-up format, gradually evolving from the most basic forms (e.g., information exchange) to more advanced ones (joint projects at various levels). Here again, the process can be initially launched at the track 2 level and gradually move to the track 1.5 and finally to the official level. In certain ways, some of unconventional security problems look less controversial and politically less toxic; if this is indeed the case, they might be at the vanguard of a new East-West European security dialogue.

It is reasonable to predict that the move towards more stable and predictable arrangements in a divided Europe will be slow and precarious. Political, institutional, and even psychological inertia of the ongoing confrontation will remain an obstacle to even very modest agreements in the years to come. Any new escalation around Ukraine or elsewhere along the line of contact between Russia and the West may well put off any practical progress in establishing the new rules of the game, even if such rules serve strategic interests of the two sides.

Looking beyond the horizon

Can Europe be reunited once again? That remains to be seen, but this is definitely not going to happen any time soon. It might take another generation in Russia and in the West to overcome the repercussions of the ongoing conflict and to restart the process that they launched together almost forty years ago. Be mindful, that the staring positions even in ten or twenty years from now are likely to be inferior to the situation of the late 1980s: forty years ago, both sides were ready to give each other the benefit of the doubt and to entertain a romantic vision of united Europe, while even in many years from now the memories of the failed attempt to build a common European security space are likely to feed skepticism and doubts about whether uniting Europe is possible in principle.

One could also imagine that most of the new long-term security arrangements in Europe will emerge as organic components of a much larger Eurasian security system that will ultimately make Europe geographically extended to include the vast Eurasian land mass. Already now, there is an ongoing process of fusion between previously separate European and the global security agendas. Leaders of Japan, Republic of Korea, Australia, and New Zealand take part in recent NATO summits, the alliance is more and more positioning itself as a global rather than a regional defense partnership. At the same time, Russia and China conduct joint naval exercises in the Mediterranean and in the Baltic Seas, Moscow upgrades its security cooperation with African nations that might have a direct impact on the European security.

Nothing suggests that this trend might stop anytime soon. If it continues, the European security agenda might become a hostage to the developments taking place in other regions of the world—like East Asia or Middle East and Noth Africa. The indivisible security approach will be the only solution to European security problems even if it turns out to be extremely hard to reach.

First published in the Security Index Yearbook by PIR Center and MGIMO University.

1. Мизин В., Севостьянов П. Архитектура европейской безопасности после 2023 года // Независимая газета, 7 марта 2023 г. URL: https://www.ng.ru/ideas/2023-02-07/7_8654_architecture.html?ysclid=lnfo4ipjmu750919194.

2. Громыко А. России и Западу нужно готовиться к постконфликтному сосуществованию // Российский совет по международным делам, 7 июля 2023 г. URL: https://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/comments/rossii-i-zapadu-nuzhno-gotovitsya-k-postkonfliktnomu-sosushchestvovaniyu/?sphrase_id=112912739.

3. Kortunov A. A New Western Cohesion and World Order // Russian International Affairs Council, September 27, 2023. URL: https://russiancouncil.ru/en/activity/workingpapers/a-new-western-cohesion-and-world-order/.

4. The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation, 2023 // Russian Foreign Ministry, March 31, 2023. URL: https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/fundamental_documents/1860586/.

5. Путин обсудил с Совбезом обновление Концепции внешней политики России // Коммерсантъ, 28 января 2022 г. URL: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/5191965.

6. Указ Президента Российской Федерации «Об утверждении Концепции внешней политики Российской Федерации» от 30 ноября 2016 г. // Официальный сайт Президента России, 30 ноября 2016 г. URL: http://static.kremlin.ru/media/acts/files/0001201612010045.pdf.

7. The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation, 2023 // Russian Foreign Ministry, March 31, 2023. URL: https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/fundamental_documents/1860586/.

8. At the same time, it is clearly stated in the Concept that the United States remains the key Russia’s interlocuter on all nuclear and strategic matters: “The Russian Federation is interested in maintaining strategic parity, peaceful coexistence with the United States, and the establishment of a balance of interests between Russia and the United States, taking into account their status as major nuclear powers and special responsibility for strategic stability and international security in general”. See: The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation, 2023 // Russian Foreign Ministry, March 31, 2023. URL: https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/fundamental_documents/1860586/

9. Академик Дынкин: Эстонизация Европы. Почему исчезла европейская безопасность? // Интерфакс, 20 июля 2022 г. URL: https://www.interfax.ru/russia/852945.

10. Nato und EU Vereinbaren “Neue Stufe” der Partnerschaft // Die Presse, January 10, 2023. URL: https://www.diepresse.com/6236098/nato-und-eu-vereinbaren-neue-stufe-der-partnerschaft.

11. МИД РФ: “перезагрузка” европейской системы безопасности обязательно случится // ТАСС, 24 марта 2023 г. URL: https://tass.ru/interviews/17357315?ysclid=lnfpyuw1hc798140800.

12. Пресс-конференция Министра иностранных дел Российской Федерации С.В. Лаврова по проблематике европейской безопасности, Москва, 1 декабря 2022 года // МИД России, 1 декабря 2023 г. URL: https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/news/1841407/.

13. Treaty between The United States of America and the Russian Federation on Security Guarantees, Draft // Russian Foreign Ministry, December 17, 2021. URL: https://mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/rso/nato/1790818/?lang=en.

14. Agreement on Measures to Ensure the Security of the Russian Federation and Member States of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Draft // Russian Foreign Ministry, December 17, 2021. URL: https://mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/rso/nato/1790803/?lang=en.

15. Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s Interview with Lenta.ru Online Newspaper // Russian Foreign Ministry, July 13, 2023. URL: https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/news/1896659/?lang=en.

16. В Генштабе заявили о создании в России двух армий и двух военных округов // РБК, 2 июня 2023 г. URL: https://www.rbc.ru/politics/02/06/2023/647943bf9a79478a6a890e20?ysclid=lnbexjci7y669162495.

17. NATO’s Military Presence in the East of the Alliance // NATO, July 28, 2023. URL: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_136388.htm.

18. Joint Press Conference by Chair of the Military Committee, Admiral Rob Bauer and the Norwegian Chief of Defence, General Eirik Kristoffersen Following the Meeting of the Military Committee in Chiefs of Defense Session, Oslo, Norway // NATO, September 16, 2023. URL: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_218279.htm?selectedLocale=en.

19. В МИД РФ учения НАТО в 2024 году назвали приготовлением военных действий против России // ТАСС, 20 сентября 2023 г. URL: https://tass.ru/politika/18796837.

20. The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation, 2023 // Russian Foreign Ministry, March 31, 2023. URL: https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/fundamental_documents/1860586/.

21. Государство-цивилизация и политическая теория // Российский совет по международным делам, 18 мая 2023 г. URL: https://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/analytics/gosudarstvo-tsivilizatsiya-i-politicheskaya-teoriya/.

22. Косачев К. Россия: «государство-цивилизация» или «анти-Запад»? // Россия в глобальной политике, 22 мая 2023 г. URL: https://globalaffairs.ru/articles/czivilizacziya-ili-anti-zapad/.

23. Frear T. Diplomatic Salvage: Making the Case for the Cooperative Airspace Initiative // Russian International Affairs Council, July 21, 2016. URL: https://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/diplomatic-salvage-making-the-case-for-the-cooperative-airsp/#:~:text=The%20Cooperative%20Airspace%20Initiative%20(CAI),This%20was%20to%20be%20achieved.

24. On a more general note, it is worth mentioning that CSBMs can be successfully agreed upon and implemented only if both sides believe that more clarity and predictability would make a contribution to their security. If the perception on one of the sides or on both sides is that a degree of strategic ambiguity and deliberate uncertainty about their intentions, plans and actions makes their positions stronger serving as a factor of deterrence, prospects for any substantive CSBMs are getting much more limited.

25. Россия и Белоруссия работают над совместной концепцией безопасности // РИА Новости, 21 сентября 2023 г. URL: https://ria.ru/20230922/bezopasnost-1897980460.html.

26. Борисов Т. В ОДКБ обсудили проблемы европейской безопасности // Российская газета, 22 февраля 2023 г. URL: https://rg.ru/2023/02/22/v-odkb-obsudili-problemy-evropejskoj-bezopasnosti.html.

27. Кремль призвал «заполнить вакуум» после денонсации договора об армиях // РБК, 29 мая 2023 г. URL: https://www.rbc.ru/politics/29/05/2023/6474725f9a7947081ee0fbd8?ysclid=lnfr9of9jx310994448.

28. Косачев: Денонсацией ДОВСЕ Россия убирает с повестки не отвечающий реалиям документ // Российская газета, 10 мая 2023 г. URL: https://rg.ru/2023/05/10/kosachev-denonsaciej-dovse-rossiia-ubiraet-s-povestki-ne-otvechaiushchij-realiiam-dokument.html

29. Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan for the Arms Control Association (ACA) Annual Forum // The White House Briefing Room, June 2, 2023. URL: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/06/02/remarks-by-national-security-advisor-jake-sullivan-for-the-arms-control-association-aca-annual-forum/.

30. Presidential Address to Federal Assembly // Official Website of the Russian President, February 21, 2023. URL: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/70565.

31. Рябков: основания для сохранения моратория РФ по РСМД исчезают из-за действий США // ТАСС, 2 октября 2023 г. URL: https://tass.ru/politika/18889831.

32. Путин допустил отзыв Россией ратификации договора о запрете ядерных испытаний // Ведомости, 5 октября 2023 г. URL: https://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/news/2023/10/05/999058-putin-dopustil-otziv.

33. On October 18, 2023, members of the Russian State Duma unanimously voted to adopt the bill on the withdrawal of ratification of the CTBT in the second and third readings. On November 2, 2023, President Vladimir Putin signed a law to officially withdraw Russia’s ratification of the CTBT.—Editor’s Note.

(votes: 2, rating: 4.5) |

(2 votes) |

Russia’s preservation of its statehood and sovereignty again becomes the main stake of the conflict. The statehood of Ukraine is another stake

Don’t Trust and Don’t Verify. New Normality for New STARTFuture belongs to the dialogue of the Nuclear Five?

Hybrid War and Hybrid PeaceThe termination of hybrid wars and their transformation into a hybrid peace is the fundamental problem of modern diplomacy

A Dangerous Gamble: The Russia-American Nuclear Game in the Ukraine CrisisAs the world's two super-nuclear powers, the relations of Russia and the U.S. are inseparable from nuclear risk

The International System between Crisis and RevolutionWorld politics is fast degrading into a zero-sum game

Eurasian Security Structure: From Idea to PracticeThe principle of indivisibility of security, not implemented in the Euro-Atlantic project, can and should become key for the Eurasian structure