European Economic History, the Debt Crisis and its Future Global Prospects

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Author: David Shternberg.

It is important to start with defining what the European debt crisis is, before we get into what has led up to causing it, and possible methods that can be implemented to prevent further crises. The European debt crisis is mainly defined by the failure of the euro. The euro unites 19 countries that use it as their primary currency, due to this quite intimately. We can safely say, since the economic collapse of the United States housing market in 2008, many of the smaller countries such as Greece, Portugal, Italy, Ireland, have all come extremely, even too close, to full economic and financial failure. Due to the euro tieing the bigger economies of Europe and foreign investors together so closely, the failure of the eurozone could end up causing global economic damage.

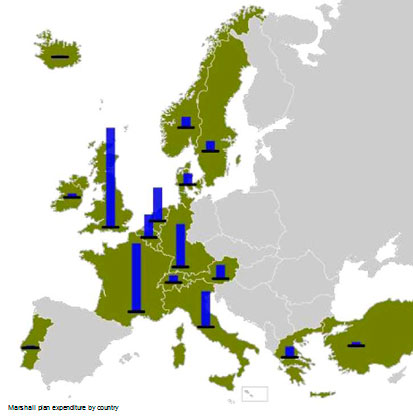

The first question is, how was the Europe originally united? Throughout history Europe was an area of conflict. War was common in Europe. Over land, or over differing religious views, Europe was almost always a warzone. Europe was also a tightly linked, but divided piece of land. Even though it was quite easy to transport good from one country to another; high fees when exchanging currencies, and high tariff fees when crossing borders made trade across countries of Europe difficult and mostly undesirable, which in cause slowed down economic growth. Ironically so, the largest conflict in Europe was also what prompted its current coalition. World War 2 decimated Europe, Causing massive damage. For example in the UK, more than a quarter of its national wealth was spent. The 1947 Paris Peace Treaties compelled Italy to pay $360,000,000. The European economy was exhausted, and drastic measures needed to be implemented to recover Europe from something this devastating. Thankfully, the US was ready to step in to aid Europe's economic recovery, with what was known as the ‘Marshall Plan’. The fastest way to rebuild was to put money under the wheels of trade, so America gave 13 billion Dollars as financial aid. The largest receivers being United Kingdom (receiving about 26% of the total), followed by France (18%) and West Germany (11%).

For this funding to have maximum effect, steel and coal tariffs started coming down, so that a steel mill in one country could sell to a construction company in another country. The Marshall plan was a success, and Europe started to regain its position as a global economic influence. The European countries who all benefited from the trading reform, decided that due to this success, a unified Europe would not only end further wars within the continent, but also allow accelerated economic growth. So, countries began to bond towards this goal. Trade barriers went down, which further lowered the cost of doing business. Once the Berlin wall finally crumbled, Europe was in a position to make such a prospect come true. 27 countries signed the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, thus creating a united Europe. This made doing business across borders very easy, however for this archetype to climax, Europe still needed to deal with one issue, which where the different currencies. In 1999, The Euro was created, solving this problem. Originally 17 countries adopted the Euro, and these were called the Euro zone. All of these discontinued their own currencies, and gave control of their monetary policy to the newly formed European Central Bank.

At this stage, Europe seemed to be on the high road to success, however this is where a very important distinction between monetary and fiscal policy comes into play. In short, the monetary policy controls the supply of money, and the quantity of money within an economy, alongside the interest rates for borrowing money.

A Fiscal policy however controls how much a government can collect in taxes, and also decides government spending with said taxes or borrowed money.

Logistically, a country can only spend what it collects in taxes. To increase spending above the tax rates, the government is forced to borrow. This is known as ‘Deficit Spending’.

To more accurately describe the effect of the crisis, and its occurrence, I’m going to use Greece as an example, due to what a massive role it played. Before the Euro, smaller, less reliable economies such as Greece had to pay massive interest rates to borrow money, and they could also only borrow a certain, fairly small and controlled amount. This was because lenders, be they countries outside the EU such as America, or private firms, didn’t feel safe lending them too much money due to the lack of stability in such a small scale economy(relative to something like Germany’s). Now however, that they were part of the Euro Area’s united monetary policy, lenders were much more lenient, meaning Greece could borrow amounts it never had access to. Also, the rates at which lending could be done decreased massively. Instead of the 18%, they could now borrow for the same incredibly low rate of 4%, just like Germany. This was possible because being part of the Euro Area is almost equivalent to sharing a credit bank account, thus if a smaller country such as Greece borrows money, and is unable to pay back the debt, bigger economies such as Germany are expected to step in and pay off the country’s tab. This expectation from bigger economies comes because they are now all tied by the same currency, thus not stepping in puts in danger all those connected to the currency. Economically, it has the potential to be a double edged sword.

Due to cheap credit becoming so abundant, Greece and other European countries were able to change up their fiscal policies to skyrocket spending, funded by the newly borrowed money. Greece and many other smaller European countries such as Portugal and Italy started to act on huge deficit spending plans. These were primarily used as political tools, for politicians to gain the majority of the vote by promising more jobs, raising pensions, and other government issued services. This of course, all being paid by the money they can now borrow. Following this, Greece, Portugal, Italy, and some other smaller countries accumulated huge debts - which they successfully paid back using more borrowed money. It turned into a loop, whereby as long as borrowing continued, so did the spending by these unbalanced fiscal policies. In Spain and Ireland, cheap credit was used to grow the housing market, just like in the USA. As credit grew more and more, debt started to accumulate, as the economies of Europe became more and more invested in each other. For example, you would have German banks lending to French companies, who would then lend to Spanish companies. Every time credit is taken, or credit is lent, the lending/ borrowing countries become invested and reliant on the country they have lent/borrowed to/from. Yes, business was easy, as intended originally by the formation of the European Union, however it also meant that Europe would face the same grim fate. As I mentioned before, the collapse of the US housing market caused a credit crisis worldwide. This, in turn stopped any borrowing.

This is where the newly adjusted fiscal policy of Greece started to backfire, not only on it’s own economy, but the whole economic stability of the Euro area. Greece could no longer pay for all the new jobs it has created, nor can it give back the money it borrowed, thus unable to pay back old debts.

Seeing as most of Europe was involved in the furious spending of borrowed money, someone had to pick up the tab, or else every country in the Eurozone would suffer. The countries that accumulated the most debt, also where the ones least able to help pay it off. Everyone started looking at Germany to bail them out.

Germany, as the strongest economy in Europe had to act - or else it was risking the currency it’s newfound economic success was based on. Germany agreed to bail out Greece, however it did so on their own terms. They implemented what are known as Austerity measures. These were in place for 2 reasons: so that this doesn’t happen again, and so the money is spent correctly for the bailout to be successful. Austerity measures mean cut government spending, decrease jobs, increase taxes in some cases. Borrowing less and paying back more debt. At first glance this seems to be a simple, and effective solution - in an economical sense it is, but in a human sense, it couldn’t get much worse for a government. Austerity measures are in place to cut government spending - however when a country’s biggest spender, it’s government, starts cutting spending, people lose jobs, benefits, pensions. People get angry and riots break out in the streets. Loss of jobs means bad political press, and emigration becomes a factor.

Worst of all, austerity doesn’t even completely end with the country paying back all its debts. As jobs decrease, general income decreases. Taxes are taken as a percentage of income, and when that decreases, so does tax revenue. This in turn means they still can’t pay back their debts.

However Germany must apply more and more Austerity measures, to make sure that Greece does not default. Even though that Greece’s economy, and the economy of the other big debtors are fairly small, due to everyone being in the Eurozone and so interconnected through fiscal policy borrowing and lending schemes, if Greece defaults - so could Spain, then Italy, then Ireland, then France, Germany, the whole of Europe. Due to foreign currency investment, and thanks to so much capital being kept in Swiss banks, the whole world is at risk of economic collapse. The debtor countries borrowed money from banks, investors, and other governments throughout Europe. As the debtor countries get closer to default, everyone who lent them money becomes weaker. And everyone who lent those lenders money also becomes weaker. And so on and so forth. Austerity measures also just aren’t enough, as they are a short term solution. Let’s say that they solve this crisis, but once Greece is bailed out nothing stops it from managing its economy in the same way. Even during the crisis, Ukraine tried to join the Eurozone for the exact same reasons. The president promised increase in jobs, higher pensions, which he would achieve of course through borrowing in the Eurozone just like Greece did, putting the European economy at risk yet again. So this is where Europe needs to take action - Either united monetary and fiscal policies, or neither.

A united fiscal policy would mean a central fiscal union on top of the monetary union - whereby countries in the Euro area would surrender sovereignty to a higher, elected power. This would mean turning Europe into the United States of Europe. A fiscal union would be able to cut government spending, how much each government would be able to borrow, and lend. It would control the economy in a way as to not risk the stability of the Euro for the benefits of one nation. Practically, its socialism on an international level - which is precisely why it’s such an unpopular opinion.

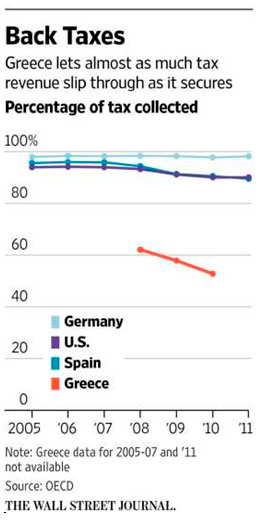

One of the biggest reasons why countries are so against this, is due to cultural differences. Let us again look Germany vs Greece. After the hyperinflation following World War I, Germany has been incredibly weary of inflation, which has lead it to being very careful about spending and borrowing. This mentality is also upheld by its citizens, who in general tend to work hard, and have little reliance on state benefits and pensions. They have also shown to happily pay their taxes, without the government having to enforce taxation nearly as much as in countries such as France, or Italy. Greeks have a very different mentality. They enjoy state benefits, early pensions, and high paying government funded jobs. Greece is also known for not collecting the majority of its taxes. It has always been this way, however joining the Euro simply amplified the problem.

One of the biggest reasons why countries are so against this, is due to cultural differences. Let us again look Germany vs Greece. After the hyperinflation following World War I, Germany has been incredibly weary of inflation, which has lead it to being very careful about spending and borrowing. This mentality is also upheld by its citizens, who in general tend to work hard, and have little reliance on state benefits and pensions. They have also shown to happily pay their taxes, without the government having to enforce taxation nearly as much as in countries such as France, or Italy. Greeks have a very different mentality. They enjoy state benefits, early pensions, and high paying government funded jobs. Greece is also known for not collecting the majority of its taxes. It has always been this way, however joining the Euro simply amplified the problem.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |