Contemporary China: Polit-economic, Socio-cultural Challenges & Prospects

(votes: 3, rating: 5) |

(3 votes) |

Princeton University, Undergraduate

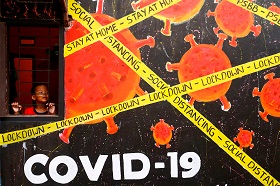

Amid the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, all eyes, yet again, are on China, which many expect, equally enthusiastically and alarmingly, to become the world’s largest economy over the next few decades. The economic growth, though, does not automatically root out all sources of disparity even if it shrinks the overall scope of inequality.

Being almost exactly in the middle on the Gini line between total inequality and full equality at 46.7, mainland Chinese wealth distribution is now more unequal than it has ever been in the nation’s history. This figure is even more startling considering the fact that the country had a very low inequality level in the 1980s, so the Chinese population is fully aware of the problem and its severity. Historically, the peaks of economic disparity have coincided with major national events, especially the Great Famine in the late 1950s, the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and the global integration that began in the late 1990s. Although the highly centralized and deeply bureaucratic nature of the Chinese government allows for the efficient implementation of inequality solutions, official poverty-reducing policies at such peaks had minimal effects.

In contemporary China, the state of inequality is essentially determined by regional differences and the countrywide urban-rural divide. Kanbur and Zhang [1] claim that the share of heavy industry in gross output values, the degree of decentralization, and the degree of openness are three main driving forces of inequality across regions. The urban-rural divide, on the other hand, is sustained by top-down regulations that affect basic human rights, such as health, housing, and mobility. One of such regulations is hukou, a system of household registration linked to social programs provided by the central government, which assigns social benefits based on the agricultural and non-agricultural residency status. As such, hukou has been a structural source of inequality since the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, as urban residents receive benefits, ranging from retirement pensions to healthcare, that are unavailable to rural residents. Chan [2] asserts that to reduce rural poverty is to end hukou, which directly impedes with rural-to-urban migration, the main means of escaping poverty in rural areas. The internal migration, including the interprovincial one from the thinly populated and deprived Western regions to the densely populated and affluent East Coast, has intensely accelerated since the 1980s. Referred to as the ‘floating population,’ rural migrants tend to circulate in-between cities rather than settle, making them in a way statistically invisible. Yet their presence in the urban landscape critically influences workforce and housing markets. Given the unparalleled magnitude of the Chinese population, housing registration, obviously, needs to operate for practical purposes, but not in its current caste-system resembling form.

Beyond adjusting its family policies to emerging social norms, the government has to offer an integration path for ostracized ethno-linguistic and religious groups. Gladney [16] claims that China, which is home to the largest Muslim minority in East Asia (around 20 million people), has so far failed in incorporating Muslims, whose self-preservation is at risk, in the national fabric in a way that is neither full accommodation nor complete separatism. Obviously, Islam and traditional Chinese beliefs have distinct worldviews. For example, Muslim Chinese evaluate development levels of majority-Muslim countries far more favorably than the Han Chinese do [17], but their co-existence over several centuries means that common ground can be found. Moreover, China’s dependence on the Middle East as an oil supplier and an export market mandates for Muslims’ acceptance in the Chinese ‘leviathan.’

Like religious ones, ethno-linguistic minorities bear discrimination in China. Wu and He [18] state that despite of the regional distribution of ethnic minorities being relatively stable from 1982 to 2005, the Han-minority disparity in education and employment amplified in the same period. After it had started identifying all 55 minorities (around 10% of the national population), which are geographically isolated not just from the Han Chinese but each other, the communist party has taken a few steps to stimulate their socioeconomic mobility, such as granting college admission bonuses. However, the country’s forceful economic transition has widened the gap instead of narrowing it, as the profit-driven private sector values economic efficiency over social equality. That is why the government must pass anti-discrimination laws that will subdue institutional prejudice against ethno-linguistic and religious minorities.

Finally, if the Chinese government makes a conscious decision to contain ever-expanding state machine or apparatus from permeating every aspect of citizens’ daily lives, allowing the society to ‘breath normally,’ it will be able to competently respond to polit-economic and socio-cultural challenges that contemporary China is confronting, such as a slower economic growth rate and elevated ethnic tensions. This is the only way to regenerate the country’s prospects.

Amid the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, all eyes, yet again, are on China, which many expect, equally enthusiastically and alarmingly, to become the world’s largest economy over the next few decades. The economic growth, though, does not automatically root out all sources of disparity even if it shrinks the overall scope of inequality.

Being almost exactly in the middle on the Gini line between total inequality and full equality at 46.7, mainland Chinese wealth distribution is now more unequal than it has ever been in the nation’s history. This figure is even more startling considering the fact that the country had a very low inequality level in the 1980s, so the Chinese population is fully aware of the problem and its severity. Historically, the peaks of economic disparity have coincided with major national events, especially the Great Famine in the late 1950s, the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and the global integration that began in the late 1990s. Although the highly centralized and deeply bureaucratic nature of the Chinese government allows for the efficient implementation of inequality solutions, official poverty-reducing policies at such peaks had minimal effects.

Global Victory Over COVID-19: What Price Are We Willing to Pay?

In contemporary China, the state of inequality is essentially determined by regional differences and the countrywide urban-rural divide. Kanbur and Zhang [1] claim that the share of heavy industry in gross output values, the degree of decentralization, and the degree of openness are three main driving forces of inequality across regions. The urban-rural divide, on the other hand, is sustained by top-down regulations that affect basic human rights, such as health, housing, and mobility. One of such regulations is hukou, a system of household registration linked to social programs provided by the central government, which assigns social benefits based on the agricultural and non-agricultural residency status. As such, hukou has been a structural source of inequality since the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, as urban residents receive benefits, ranging from retirement pensions to healthcare, that are unavailable to rural residents. Chan [2] asserts that to reduce rural poverty is to end hukou, which directly impedes with rural-to-urban migration, the main means of escaping poverty in rural areas. The internal migration, including the interprovincial one from the thinly populated and deprived Western regions to the densely populated and affluent East Coast, has intensely accelerated since the 1980s. Referred to as the ‘floating population,’ rural migrants tend to circulate in-between cities rather than settle, making them in a way statistically invisible. Yet their presence in the urban landscape critically influences workforce and housing markets. Given the unparalleled magnitude of the Chinese population, housing registration, obviously, needs to operate for practical purposes, but not in its current caste-system resembling form.

Furthermore, the government has to instill lawful procedures for assimilating rural emigrants, who, alongside their children, confront serious predicaments in the multidimensional process of urban societal integration. Having crossed 250 million by 2015, the Chinese migrant population is the largest in the world; however, due to official restrictions, especially hukou, the interprovincial migration in China is even more administratively challenging than the state-to-state migration in the United States. These restrictions equally impact children, both who stay behind in rural areas, the so called ‘left-behind children,’ and those who with their parents move to or are born in cities. Liang [3] suggests that further research on the internal migration be devoted to the mobility of minority groups, such as Muslims, and finding out if the importance of hukou is declining for the new generation of migrant workers. Even if this were true, the government is not free from providing additional ameliorating measures for migrants, for example, a cheaper, less complicated way of making remittances to countryside family members and other relatives and food stamps until the job acquisition.

Big companies, in turn, should offer educational enrichment programs to their urban and rural employees to meet the international employment competition. Despite its unchallenged advantage in sheer numbers, the Chinese workforce is relatively weak in terms of education levels, which in long run can create a human capital crisis in mainland China, as the upper secondary school attainment is a crucial ingredient for the country’s continued economic growth. Khor and others [4] estimate that only less than 25% of the Chinese labor force have completed secondary education, a significantly lower figure than around 55% average across all G20 countries. The Ministry of Education pompously inflates official figures. Considering that China is gradually transitioning from an upper middle-income state to a developed economy and that this transition means supplanting low-wage, labor-intensive manufacturing with high-wage, high value-added industries that require knowledgeable cadres, the Ministry of Education is obliged to bring education programs and workplace demands in unison. Lamentably, the government routinely overlooks school attainment levels of its citizens, because service and manufacturing industries, the titans of national employment, hire staff based on discipline indicators and occupational skillsets rather than school performance.

The guiding principle of reforms must be making the Chinese education system more inclusive. Wu and Zhang [5] claim that recent expansions in this field have benefited urban women more than any other social group and that despite an overall increase in educational equality, the urban-rural contrast is ever stark; however, this is in line with the worldwide trend, which shows that educational inequality as a whole is declining with the continued economic growth, but the urban-rural divide permeates in face of modernization. To reduce this divide, the government must rescind educational policies that favor city students, starting with the elimination of standardized testing as an upper secondary school entrance requirement, which highly favors urban over rural students. Having completed superior middle schools and resources to private tutoring, urban students disproportionately beat their rural counterparts out, keeping the cycle of urban-rural divide in education spinning.

Beyond the education system, the government has to transform workplace structures, foremost by substituting danwei, a work unit with communist roots that in the form of ‘organized dependency’ maintains the state administrative hierarchy, with non-state labor unions or guilds. Xie, Lai, and Wu [6] assert that even if some of its original functions, such as housing and health subsidies, have declined with the rise of private sector, danwei continues to play a central role in the social stratification and occupation mobility in post-reform China, influencing earnings (salaries are low in mainland China) more than benefits — a reverse was true in pre-reform China. Not as interested in maximizing occupational profits as in maintaining ties with the ruling authority, danwei stratifies the contemporary Chinese society because of its more equal nature than the market justifies. That is why independent labor unions, which can provide not only similar benefits, such as a health coverage, but also guarantee adequate wages that the current work unit system compromises for the sake of social advantages, ought to overtake danwei.

Another factor hampering the national progress is the Great Firewall, the combination of legislative actions and technologies enforced by the government to regulate the Internet domestically. King, Pan, and Roberts [7] emphasize that as opposed to the popular assumption that any government-critical content is taken down, the Internet censors are actually oriented to the content with a collective action potential, notwithstanding with its underlying attitude towards the government. Yet history, in particular the Great Famine, has shown that the Chinese people, in accordance with the Confucian values, tend to blame not the ruling authority, but local officials for their problems. This, coupled with the fact that a common Chinese online user self-censors, demonstrates that the Internet censorship is an excessive administrative measure. This measure deters the info-communicational advancement of the mainland Chinese population, which lacks a unified intention for the regime change.

Abolishing hukou, danwei, and the Great Firewall schemes, as well as reforming the education system, requires a coordinated national effort between the central government and provincial leaders. The majority of regional officials, though, behave not as much in response to the countrywide market-preserving federalism as within the multidivisional-form structure of the Chinese economic sector. As the political status of a Chinese province directly correlates to its economic power, the post-Mao China witnessed political conformity being largely supplanted by the economic performance as a chief competence-related indicator. Li and Zhou [8] confirm that the local GDP growth rate is directly proportional to the official’s turnover, which is nonlinear due to the effect of performance during tenure as a whole over a single year being more important. Besides promotion as an instrument of personnel control, the ruling government exercises termination, transition, and retirement, for example, successful Chinese officials, whose merits are almost exclusively measured in financial terms, receive honorary, albeit powerless, titles before their official retirements.

The economic performance endures as an effective political tool as long as the Chinese economy continues to grow; however, in light of 6% economic growth rate as the new normal and the ongoing trade war with the United States, securing successful operations of local officials principally through economic incentives seems myopic from the central government. This needs to complement its existing economic leverage in governing localities with more stable social factors, especially given that governors are inclined to artificially boosting financial figures of their provinces. This not only results in distorted reports on living conditions of people, but also in the national prevalence of the economic growth at all costs, which only exacerbates intra-regional inequalities in terms of education and employment prospects. Xie and Zhou [9] note that despite being comparable in both the total area and income distributions as well as the subordination of state/provincial officials to the federal/central government, USA, where a family structure combined with race and ethnicity significantly influences lifetime earnings of every person, has had a smaller rate increase in economic inequality over the last decade than PRC.

Evidently, the Chinese economy is neither laissez-faire nor Leninist, but rather a unique case. Oi [10] claims that the economic growth of China is embedded in the system in which local officials, acting as CEOs, treat local enterprises under administrative control as parts of a larger corporate whole. Accordingly, the national economic growth rests largely on the rural industry, which has experienced an upsurge following a few amendments to the Maoist system, especially de-collectivization of agricultural production and the fiscal reform that allows for the autonomy over any local surplus. To strengthen corporatism in their provinces, officials pursue one of three methods: misappropriating marked funds coming to local farmers from the central government; licensing non-bank credit institutions that avoid central regulations — a more legal way; and granting small loans from bureau funds. Having been long ignored by the central government because of its quintessential role in the Chinese economic expansion, local state corporatism is directly responsible for the accumulation of debts worth $5.8 trillion. This issue is especially problematic in light of the Chinese market leaning more and more towards privatization — a process catapulting a new type of corporate elite into prominence in the midst of this managerial revolution.

Whether the new corporate elite will push the country to approach the capitalist economy model established in free states is a critical question. Walder [11] notes that both economic assets and ties to the central government of this new elite are equivocal, so each sector — state-owned, privatized, transactional, and entrepreneurial — demands to be separately analyzed. Corporate networks mapped via interfirm webs can also point to China’s course moving towards or away from being a state where wealth and political power are synonymous. Arguably, the new corporate elite will maintain close political ties with the ruling government. Alternatively, it can act as a political opposition by challenging the status quo whenever appropriate. The ruling party is absolutely creditable to a degree for the country’s success, but being completely unrestrained, it will fail to perceive overstretched borders of its regulations, including the Great Firewall, as the established framework is self-damagingly hostile to change. The new corporate elite has a potential to become a powerful intermediate agent safeguarding the consolidation of the social contract between the Chinese people and state, and it should not miss this exciting chance. Still, where there is the elite, a clash with interests of people is inevitable, and China has yet to match its powerful economic status with a benevolent state image internationally.

Considering Chinese citizens’ rising awareness of universal human rights violations in the country, especially with regard to family and religious domains, both of which an almost uninterrupted nature of the Chinese civilization has substantially burdened by its institutional emphasis on the former and a lack of such emphasis on the latter, the ruling party can no longer afford to ignore its obvious shortcomings in dealing with ethno-linguistic and religious minorities and novel family structures emerging out of the tension between persisting cultural customs and changing social behaviors in the contemporary Chinese society. Raymo and others [12] claim that the second demographic transition, which is characterized by a variety of living arrangements and a disconnection between marriage and procreation, is more conspicuous in the East than in the West. Traditionally, East Asian families are patriarchal, patrimonial, patrilineal, and patrilocal, but the global rise of the women’s socioeconomic status has undermined this organization.

Although women in mainland China have advanced their social status over the last decade, they continue to be disadvantaged in terms of household labor, education, salaries, and leadership positions due to gender bias. For example, parents disproportionately put educational resources in sons at the expense of daughters, as they expect the former to materially support them in their old age and the latter to be taken care of by husbands’ families. Men, on the other hand, face an extreme competition not only in employment, but also in the marriage market. Xie [13] notes that Chinese men find it increasingly difficult to marry partly because of the prevailing social hypergamy exacerbated by present economic pressures. In addition, men massively outnumber women as a result of a higher cultural and economic value assigned to them. Of course, a growing number of single, unemployed men has a socially disruptive potential, but being an authoritarian state with Confucian values, China would be resistant to the gang culture that has eroded Latin America.

Made in China: Why Would China Export its Governance Model?

Without taking demographic changes into account, the government cannot adequately address such issues as population aging, labor force shortages, public health care, family planning, and retirement arrangements. The rapid pace at which China has been modernizing since its global integration began in the late 90s only intensifies this challenge. Peng [14] states that as the age of first marriage has gone up to twenty-five, the birth rate has dwindled (Japan has the lowest in the Far East), more individuals prefer not to marry (childbearing outside wedlock is still very rare), and more couples choose to cohabitate. China is achieving its second demographic transition in a relatively compressed period of time.

It is ambiguous how official Family Planning Commission programs have influenced this transition.` For example, the One-Child Policy, which the government ended after 35 years, might not have caused a supposed fertility decline in the country given that Chinese families have been naturally leaning towards having two or less children since 1990s. Family policies in general apply differently to urban and rural areas. For instance, while the urban implementation of pensions has lifted an adult’s traditional economic duty to provide for elderly parents, transforming the nature of monetary support from financial to symbolic, this duty remains in force in countryside. Xie and Zhu [15] emphasize that in cities compared to married sons married daughters give more money to their parents contrary to custom. This can be explained by the fact that over the last decade, women have outranked men in educational attainment, bolstering their job income.

Beyond adjusting its family policies to emerging social norms, the government has to offer an integration path for ostracized ethno-linguistic and religious groups. Gladney [16] claims that China, which is home to the largest Muslim minority in East Asia (around 20 million people), has so far failed in incorporating Muslims, whose self-preservation is at risk, in the national fabric in a way that is neither full accommodation nor complete separatism. Obviously, Islam and traditional Chinese beliefs have distinct worldviews. For example, Muslim Chinese evaluate development levels of majority-Muslim countries far more favorably than the Han Chinese do [17], but their co-existence over several centuries means that common ground can be found. Moreover, China’s dependence on the Middle East as an oil supplier and an export market mandates for Muslims’ acceptance in the Chinese ‘leviathan.’

Like religious ones, ethno-linguistic minorities bear discrimination in China. Wu and He [18] state that despite of the regional distribution of ethnic minorities being relatively stable from 1982 to 2005, the Han-minority disparity in education and employment amplified in the same period. After it had started identifying all 55 minorities (around 10% of the national population), which are geographically isolated not just from the Han Chinese but each other, the communist party has taken a few steps to stimulate their socioeconomic mobility, such as granting college admission bonuses. However, the country’s forceful economic transition has widened the gap instead of narrowing it, as the profit-driven private sector values economic efficiency over social equality. That is why the government must pass anti-discrimination laws that will subdue institutional prejudice against ethno-linguistic and religious minorities.

Finally, if the Chinese government makes a conscious decision to contain ever-expanding state machine or apparatus from permeating every aspect of citizens’ daily lives, allowing the society to ‘breath normally,’ it will be able to competently respond to polit-economic and socio-cultural challenges that contemporary China is confronting, such as a slower economic growth rate and elevated ethnic tensions.

References:

1. Kanbur, R. and Zhang, X. 2005. “Fifty Years of Regional Inequality in China: A Journey through Central Planning, Reform, and Openness.” Review of Development Economics 9(1), pp. 87-106.

2. Chan, K. W. 2013. “China: Internal Migration.” The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration.

3. Liang, Z. 2016. “China's Great Migration and the Prospects of a More Integrated Society.” Annual Review of Sociology 42, pp. 451-471.

4. Khor, N., Pang, L., Liu, C., Chang, F., Mo, D., Loyalka, P., and Rozelle, S. 2016. “China’s Looming Human Capital Crisis: Upper Secondary Educational Attainment Rates and the Middle-income Trap.” The China Quarterly 228, pp. 905-926.

5. Wu, X. and Zhang, Z. 2010. “Changes in Educational Inequality in China, 1990–2005: Evidence from the Population Census Data.” Research in Sociology of Education 17, pp. 123-152.

6. Xie, Y., Lai, Q., and Wu, X. 2009. “Danwei and Social Inequality in Contemporary Urban China.” Research in the Sociology of Work 19, pp. 283-306.

7. King, G., Pan, J., and Roberts, M.E. 2013. “How Censorship in China Allows Government Criticism but Silences Collective Expression.” American Political Science Review 107(02), pp. 326-343.

8. Li, H. and Zhou, L.A. 2005. “Political Turnover and Economic Performance: The Incentive Role of Personnel Control in China.” Journal of Public Economics 89(9), pp.1743-1762.

9. Xie, Y. and Zhou, X. 2014. “Income Inequality in Today’s China.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(19), pp. 6928-6933.

10. Oi, Jean C. 1995. “The Role of the Local State in China's Transitional Economy.” The China Quarterly 144, pp. 1132-1149.

11. Walder, A. G. 2011. “From Control to Ownership: China's Managerial Revolution.” Management and Organization Review 7(1), pp. 19-38.

12. Raymo, J.M., Park, H., Xie, Y. and Yeung, W.J.J. 2015. “Marriage and Family in East Asia: Continuity and Change.” Annual Review of Sociology 41, pp. 471-492.

13. Xie, Y. 2014. “Gender and Family” in The Oxford Companion to the Economics of China, pp. 495-501. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

14. Peng, X. 2011. “China’s Demographic History and Future Challenges.” Science 333(6042), pp. 581-587.

15. Xie, Y. and Zhu, H. 2009. “Do Sons or Daughters Give More Money to Parents in Urban China?” Journal of Marriage and Family 71, pp. 174-186.

16. Gladney, D.C. 2003. “Islam in China: Accommodation or Separatism?” The China Quarterly 174, pp. 451-467.

17. Lai, Q. and Mu, Z. 2016. “Universal, yet Local: The Religious Factor in Chinese Muslims’ Perception of World Developmental Hierarchy.” Chinese Journal of Sociology 2(4), pp. 524-546.

18. Wu, X. and Gloria He. 2016. "Changing Ethnic Stratification in Contemporary China." Journal of Contemporary China 25(102), pp. 938-954.

(votes: 3, rating: 5) |

(3 votes) |

China’s two-arm approach of strategically opening and closing will likely continue

Made in China: Why Would China Export its Governance Model?To better understand China, you need to become China

Global Victory Over COVID-19: What Price Are We Willing to Pay?The First Take on Humanity’s KPI in Combating the Coronavirus

The Battle of “Coronavirus Narratives”: Three Lines of Defence Against ChinaThe West, particularly the United States, is crying out for an alternative to the Chinese coronavirus narrative. And now more so than ever, as the outlines of a post-corona bipolar world are coming into sight