Separatism in the European Union

Artur Mas i Gavarró, President of the Generalitat

de Catalunya

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Doctor of History, Chief Researcher of the RAS Institute for European Studies

Within the range of the most burning international issues of the end of 2012– beginning of 2013, the revival of separatist sentiment in certain European countries is a point of special interest. Representatives of this segment of the European partisan spectrum achieved considerable success in the local elections in Catalonia and Flanders. The leaders of the Scottish separatists forced London to negotiate the issue of the referendum on independence of this part of the United Kingdom. Separatists of the Northern League have resumed asserting the frailty of the present unitarian Italian state.

Separatism is most apparent in certain regions of such European Union members as Great Britain (Scotland, Northern Ireland), Spain (Catalonia, Basque Provinces), Belgium (Flanders), Italy (northern provinces), and France (Corsica). Separatist activity manifests not only within the political sphere, but sometimes (in Northern Ireland, Basque Country and Corsica) it also translates into terrorist attacks. A considerable number of separatists tend to seek concessions from the central authorities through negotiations, demanding referenda on the independence of respective territories (Scotland, Catalonia). However, part of the population (especially national minorities) is unprepared for their regions to secede from existing states. Legislative barriers delineated in constitutions and other acts of state also complicate this process. Furthermore, the European Union is unwilling to grant automatic entry to countries with newly acquired statehood. This road is especially challenging in the context of the current economic and financial crisis, as the latter calls into question the very possibility of existence of new states without outside support.

Separatists in Europe: Strangers among Friends

Within the range of the most burning international issues of the end of 2012– beginning of 2013 (after the Eurozone crisis and the tragic developments in the Middle East), the revival of separatist sentiment in certain European countries is a point of special interest. Representatives of this segment of the European partisan spectrum achieved considerable success in the local elections in Catalonia (Spain, November 2012) and Flanders (Belgium, October 2012). The leaders of the Scottish separatists, having won the local elections of 2011, forced London to negotiate the issue of the referendum on independence of this part of the United Kingdom. Upon the collapse of the Berlusconi cabinet, separatists of the Northern League, a former partner in Silvio’s coalition, have resumed asserting the frailty of the present unitarian Italian state. In November 2011 the League demanded to establish a “Parliament of the North” with somewhat broad administrative powers.

Separatist Parties

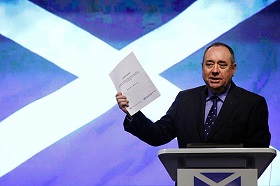

Though the political magnitude of separatist forces in a number of European regions is highly varied, today one can identify a number of major regional parties which are more influential than the local branches of national parties. In Catalonia it is the Convergence and Union alliance, whose leader, Artur Mas, is the current President of the Catalan autonomous government. The supreme body of executive power in Scotland is headed by Alex Salmond, leader of the Scottish National Party. The New Flemish Alliance is highly popular in Flanders (Belgium); in the local elections of October 2012 it collected more than 30% of the votes. Its leader, Bart de Vever, is burgomaster of Antwerp, the second largest Belgian city. Sinn Fein is broadly represented in legislative and executive bodies of Northern Ireland. The above-mentioned Northern League confidently wears the crown of political supremacy in local bodies of power in Northern Italy. Separatists are also widely represented in the national parliaments of those countries, and their number therein is actually growing on average. After the 2011 parliamentary elections in Spain, for the first time in history representatives of the Basque separatist coalition of Amaiur became members of the Spanish supreme legislative body. It's also worth noting that many of the aforementioned parties are represented in the European Parliament.

First Minister of Scotland Alex Salmond said

it was 'game on' for the independence referendum

David McCrone: Prospects of Scottish

Independence

The boom of separatist activity can be viewed in the context of the internal political situation in the different countries. However, specific national nuances cannot be considered independently of the overall socio-economic and financial instability in the European Union. We should not disregard the deep historic roots of such an internally contradictory phenomenon as European separatism.

European “Pain Points”

In retrospect, separatism in a number of European countries was engendered by the conflict of ethnic, national, confessional and culturally isolated minorities with the dominant ethnic groups which infringed their sovereign rights.

Applying this pattern to Great Britain, one can see that Scottish separatism stems from the once obvious balance between the two royal families reigning in Great Britain before the Acts of Union of 1707 – the English and Scottish dynasties. The Scots can hardly accept that today they are nothing more than “junior partners”, moreover ones being deprived of a whole range of rights enjoyed by the English. Scottish separatism was further boosted by the discovery of oil and gas deposits off the shore of Scotland late in the 1970ies. Another factor is the separatism of Northern Ireland, rooted in the sentiment of Catholics living in the Northern part of the island craving for the union with the larger part of Ireland independent from the Protestant British.

The second European “pain point” suffering from separatism is Spain, with its two regions historically discontented by their status: Catalonia and the Basque Country. The population of these Spanish regions has always suffered from disregard of their national, cultural and language special features by the central authorities. Franco’s dictatorship forced complete unification – the Catalans and Basques were stripped of all regional rights. They were restored only upon resumption of the democratic rule later in the 20th Century. The economic factor also plays an important role, as today Catalonia accounts for one fifth of the Spanish GDP.

The trend of downgrading the sovereign rights of minorities (identical to that in Spain) also developed in Belgium. The hegemony of French-speaking Wallonia over Dutch-speaking Flanders was apparent until the mid-20th Century. Politically, for many years the Flemish were “junior partners” of the Walloons. The situation changed when the Flemish outnumbered the Walloons, and the Flemish economic potential became a decisive factor in the Belgian economic life.

Economy is the alpha and omega of the North Italian separatists, who believe that their industrially advanced region is the breadwinner for the corrupt Italian center and, especially, for the economically depressed and criminalized south.

The problem of acute confrontation between one segment of the population and the central authorities is not confined to the above-mentioned European countries alone. Lately, the inhabitants of Greenland and the Faeroe Islands have started to claim sovereign rights in Denmark. The Turks in Bulgaria are voicing their own problems (above all, in terms of cultural, national and language autonomy), as are Hungarians in Romania and Slovakia and Russian-speaking minorities in the Baltic States. However, their ultimate goal is respect of minority rights within the framework of existing states, instead of secession or unification with countries of ethnically and linguistically homogeneous population.

From Terrorism to Negotiations

Quite recently a certain proportion of European separatists resorted to violent methods of struggle. Suffice it to recall such actions by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in Ulster (Northern Ireland), or the terrorist attacks of the Basque ETA, so typical of the end of the 20th Century. It is also worth noting the terrorist attacks in Corsica perpetrated by those who are unprepared to put up with French jurisdiction over the Mediterranean island.

Today, these extreme separatist moves are nothing more than a faint echo of the events of the recent past. The moderate wing of the separatist forces, represented by the parties and movements popular in their respective European regions, chose the path of negotiations with the central governments and achieved positive results. For one, the British Labor Government granted the right to convene regional parliaments with a sufficiently broad range of powers to Scotland and Northern Ireland. In 2011-2012 London made concessions to Edinburgh in the field of financial and tax independence. Catalan separatists secured a constitutionally formalized recognition of their native land by the central authorities as a special entity of the Monarchy of Spain. Progress was made in the negotiations between separatist leaders and Madrid officials as regards the referendum as an initial step towards the potential establishment of an independent Catalan state. However, official Madrid was quite negative in its response to the declaration of sovereignty of Catalonia passed by the Catalan Parliament on January 23, 2013. Pursuing the same purpose, the political leaders of the Basque Country have also chosen the path of negotiation. The ETA has openly declared its renunciation of armed struggle. The IRA has also commited to voluntary dissolution in Northern Ireland.

In general, politically active separatist forces are ready to achieve their goals through democratic dialog, without giving up such forms of resistance as mass protests, regional strikes or use of the mass media and the Internet for their purposes.

The Separatists’ Chances

Roberto Maroni, leader of the Northern League,

a party seeking autonomy or independence for

Northern Italy or Padania

Having chosen a means of implementing their goals, separatist leaders cannot but take into account their rather flimsy chances of achieving what Russian Bolsheviks in 1912 imprudently called “the right of nations to self-determination up to secession”.

First of all, by no means all inhabitants of the respective areas of separatism would be prepared to give up their existing statehood in favor of a highly doubtful chance to acquire a “new homeland”. The recent opinion polls held in Catalonia and Scotland prove that if the referendum process were launched, separatists would-be unable to secure a stable majority of voters. Opponents of separatism employ methods of political struggle identical to those used by separatists, both locally and in the center. Numerous rallies against secession were held in Catalonia and Scotland late in 2012. Early in 2013 in Belfast, the supporters of Northern Ireland’s membership in the United Kingdom demanded permanent flying of the Union Flag from the façades of regional authorities’ premises. Dozens of thousands of opponents of Flemish separatists flood the streets of Brussels in support of the integrity of their country.

Let us point out another important aspect: the secession procedure in Spain and Great Britain (to take two examples) demands the consent of the other members of the respective federations, including the approval of central parliaments. National monarchs shall have the last word. In particular, King Albert II of Belgium has repeatedly claimed that he is against Belgian self-destruction. King Juan Carlos I of Spain takes a similar stance. The Catholic church of Spain is strongly opposed to Catalan and Basque separatism. The economic component of a schism is yet another issue high on the separatists’ agenda, as the new, greatly coveted state would immediately lose all economic ties currently available within the framework of the mother-state. A sharp decline in popular sentiment towards reunification with Ireland among Ulster Catholics is also illustrative. The latter are fully aware that today their longed-for homeland is one of the economically and financially weakest parts of Europe.

The issue of acquisition of sovereignty over natural resources also remains unclear. In particular, British authorities have quite explicitly declared that Scottish shelf oil deposits in the North Sea cannot become the sole property of Edinburgh.

A substantial hurdle in the separatists’ way is the stance of the European Union. The new version of its constitution states that newly established countries cannot automatically become EU members, but have to comply with a highly complex procedure (as the experience of East European neophytes confirms) of acquiring full membership. As regards the accession of new members, NATO shares the same viewpoint. Finally, the persistent crisis of the Eurozone, growing inflation and unemployment, practically unmanageable growth of immigrants from the poorest countries, unresolved environmental and energy problems – all these, among many other factors, force separatists to make more sober assessments of their chances.

Without giving up their ultimate goal of independence, today they seek the implementation of a more modest program – acquiring new concessions from the central government, primarily in the context of economic support of the regions and of consolidation of cultural and language identity in the areas of separatist activity. While recognizing the fairness of such demands, one should emphasize that under the conditions of persistent crisis of the European Union, separatism becomes a destructive factor complicating the formation of the well-balanced Europe which EU leaders claim to seek.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |