One Year After Haiyan: Time to Recalibrate Humanitarianism?

Residents ride their motorcycles past a ship

which ran aground during last year's Typhoon

Haiyan in Tacloban city in central Philippines

November 4, 2014

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, RIAC expert

One of the most devastating typhoons in modern history hit the Philippines one year ago. Hayian (Yolanda) left the population and economy severely damaged: about 6,300 people dead, 4.3 million internally displaced, and economic damage in excess of $2 billion – an enormous sum for a developing economy. As the humanitarian agenda continues to gain momentum within the political discourse, the question remains: are we doing any better in response to such crises?

One of the most devastating typhoons in modern history hit the Philippines one year ago. Hayian (Yolanda) left the population and economy severely damaged: about 6,300 people dead, 4.3 million internally displaced, and economic damage in excess of $2 billion – an enormous sum for a developing economy. As the humanitarian agenda continues to gain momentum within the political discourse, the question remains: are we doing any better in response to such crises?

A brief history of the humanitarian reform

The United Nations is usually condemned for its inability to conduct comprehensive reforms, with this criticism chiefly directed at the UN Security Council. However, this is not the case, the UN is an organization that has a large number of bodies and other institutions within its system. While individual states can hardly achieve agreement on what the future Security Council or General Assembly should look like, reform in one of the most important and efficient areas of UN operation – namely, humanitarian work – took place in 2005.

Humanitarian Reform envisaged a variety of serious changes in how the UN (as well as states, other international organizations, and NGOs) should react to humanitarian crises. First, it provided a well-balanced coordination mechanism, based on the activities of the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) and the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA). This mechanism is hopefully broad enough to include not only the UN, but also states (both donor and recipient), international and local NGOs, including the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. This multi-dimensional system that embraces global, regional, national, and local actors has made it possible to coordinate the international community’s humanitarian response in an effective and targeted manner.

Despite the GHP’s failure, it marked a very important development in humanitarian affairs: an attempt to move away from the previous mind-set by limiting political influence and involving new actors

Importantly, Humanitarian Reform also involved introducing the ‘cluster approach’. It defined the basic areas for humanitarian action (e.g., food security, emergency communication, early recovery, logistics, nutrition, etc.) and established a link between these fields and other actors (mostly UN bodies), thus making them ‘responsible’ for their part of the job. Such links seem to make the whole humanitarian assistance process run more smoothly, as all those engaged would need to concentrate solely on the tasks in which they have considerable experience, since most coordination work relies on the IASC and UN OCHA.

for International Development

Aerial view of Tacloban after Typhoon Haiyan

It is not only the UN that reformed the vision and mechanism of modern humanitarianism: another contemporary trend involves the growing engagement of non-state actors via non-state networks or systems embracing different types of participant. One such network, which may be seen as a successor of the UN Humanitarian Reform, is the Global Humanitarian Platform. Launched in 2006, it aimed at developing the process started within the UN to include local NGOs and other civil society organizations and create a ‘humanitarian space’ free from politics. The platform, however, was not that successful: it was mostly active up until 2010, data is not available on their website.

Despite the GHP’s failure, it marked a very important development in humanitarian affairs: an attempt to move away from the previous mind-set by limiting political influence and involving new actors – chiefly non-state actors. The Sphere Project in their ‘Humanitarian Charter’ also noted this change.

The third aspect of this reform is states’ changing attitudes and approach to humanitarian affairs to include the notion and practice of ‘disaster diplomacy’[1]. There are various reasons for this change: the aim of promoting country’s image via this type of soft power, or the desire to use another sphere as a foreign policy tool. Despite this rationale, UN OCHA Humanitarian Data and Trends 2013 show states’ increasing interest: the volume of financial aid almost doubled from 2000 to 2011.

It may be argued that the humanitarian arena is in line with the concepts proposed by J. S. Nye[2], or even M. Naim[3], regarding the diffusion or even the ‘end of power’. In addition to establishing relatively stable and efficient coordination mechanisms, humanitarian reform enlarged the amount of legitimate actors, ‘spreading power among others’ and to some extent decreased the state’s and as some major international organizations’, monopoly on humanitarian affairs.

Philippines as a benchmark

There are various different reasons to choose the Haiyan Typhoon, and its humanitarian aftermath as a good example for evaluating the reform: it is relatively recent and includes a variety of actors as well as coordination mechanisms. This, combined with the disaster’s complicated consequences, make it a good test of the international community’s resolve regarding the humanitarian response.

As the first report by OCHA (November 12) stated, the disaster affected almost all key spheres of life, with the local population facing danger in food and safe drinking water supplies, possible injuries and lack of sanitation among other imminent and potential problems. With 6,300 people dead, it affected over 13 million people across the Philippines (4.3 million lost their homes), creating not only an immediate challenge for the government and the humanitarian community – assisting those in acute need – but also the long-term task of implementing recovery.

Despite the typhoon’s severity (some say it was the worst to make landfall in recent history), the response was timely and effective: much of the damage was repaired within 6 months, and in June 2014 UN OCHA Humanitarian Country Team stated that the Typhoon Haiyan response officially moved to recovery. Whom can this success be attributed to?

As the OCHA Inter-cluster Coordination Group stated in their Final Periodic Monitoring report of August 2014, the UN humanitarian system displayed great efficiency in early response, providing over 3.7 million people with food via the so-called ‘Haiyan-corridor’, 570,000 shelters (twice the initial estimate), broad debris-cleaning works, child vaccination, etc. Monitoring and information-sharing systems also proved effective – not only at the global level, but also on the local, most crucial, level, which even included the Philippines military, via the UN OCHA system.

The cluster system has a very strong accountability-checking mechanism with highly transparent reporting – in fact, anyone interested in the issue can check the website and find all (or almost all) the relevant information.

Funding, however, still leaves a lot to be desired: the same FPM report noted that as of August 31, 2014, overall financial support amounted to $470 million out of the required $776 million – in other words, the humanitarian response is still lacking 40.4 % of required funding. Another problem is the lack of international staff: when the disaster struck, UN OCHA had only 172 staff members across the Asia Pacific region – compared to 884 in Africa[4].

It is important to note that the cluster system has a very strong accountability-checking mechanism with highly transparent reporting – in fact, anyone interested in the issue can check the website and find all (or almost all) the relevant information. Compared to countries’ reports, UN bodies are detailed: bringing the much-needed legitimation to both the donor and recipient side and proves the ‘humanitarian’ character of their actions.

Donor countries, despite their role in providing vast amounts of material resources, cannot be considered among the reasons for its smooth cooperation. In fact, the reverse is true, and the Haiyan case is a vivid example of aid politicization: the United States helped financially, and backed their support with serious military presence (including 13,000 troops, warships, and an aircraft carrier with its strike group). This is understandable, since the Philippines is a US military ally in the region. On the other hand, China, involved in a territorial dispute with the Philippines over islands in the South China Sea, initially agreed to send only $100 000 and raised the amount to $2 million only later - so as not to damage its image.

On the other hand, NGOs within some donor states were extremely proactive, sometimes gathering more resources than their countries: while in the UK the state provided $121 million and NGOs exceeded this sum by $31 million, in Switzerland the non-governmental sector exceeded their government’s efforts more than ninefold. This highlights not only the willingness of such actors to participate in humanitarian affairs, but also their ability to have an impact.

There are still concerns about the ability to coordinate NGO efforts and the international community’s strategies more broadly. The key to an effective emergency response lies in the national, or local, actors and community-based response[5]. In this sense, as some field specialists noted, comparing the Haiyan response to those of hurricane Katherine and the Haiti earthquake, that ‘we [humanitarian organizations] do not learn from our mistakes, we make the same mistakes’. In addition to the need for a more ‘field focused’ approach, there is a structural foundation for it – regional coordination networks, such as ASEAN’s AADMER Partnership Group, Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN) and others. Successful cooperation between global, regional and local entities would result in not only a better response, but also, more importantly, enhanced preparedness and overall resilience.

Response vs. resilience

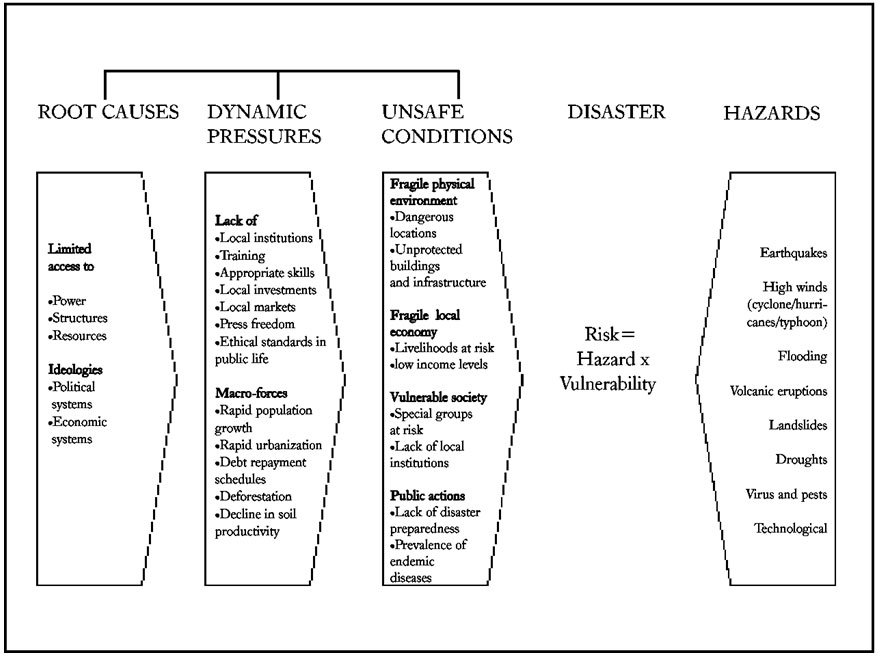

P. Blaikie et al in their theoretical work add an interesting concept (‘the progression of vulnerability’) regarding the whole idea of disasters, risk and, consequently, response, which is summed up in the next graph.

To put it simply, one of the main ideas of this approach is that a ‘disaster’ is not simply an earthquake or a tsunami, but a combination of these events, known as ‘hazards’, and ‘risks’ – such as limited access to power or resources, lack of training or local institutions, unprotected infrastructure, or vulnerable society, i.e. ‘unpreparedness’ for those hazards. No matter how fast or effective the international response may be, it will still not be enough if the population, local authorities, organizations and others lack resilience.

Donor countries, despite their role in providing vast amounts of material resources, cannot be considered among the reasons for its smooth cooperation.

In terms of humanitarian assistance, what matters is not just the amount of money given, but also how it is given. This means that aid agencies and donors must assess the local society, its socio-economic circumstances – hence the need for a community-based approach. It also means that proper humanitarian assistance comprises not only response, but also resilience and preparedness.

In these terms, a more beneficial way to respond to disasters is not just to wait for them and react rapidly, but to make a strong basis for local actors, communities and NGOs – including, of course, their cooperation with states and international organizations. This policy could not only decrease the damage and death toll in f humanitarian emergencies, but will inevitably have a positive impact through ‘depoliticisation’, since:

a) Communities and local NGOs are, compared to states, chiefly preoccupied with humanitarian problems, not politics: it is part of their raison d’etre and their interests.

b) A local-based state policy will allow more resources (financial, material, expertises, etc.) for those actors. It will nevertheless retain its limited ability to influence them, but it would be harder to use humanitarian tools for strictly political goals.

c) There are examples of non-state actors who, while acting in accordance with their humanitarian agenda, influenced the state’s foreign policy and achieved a positive goal. One of the most vivid examples may be the Greek-Turkish rapprochement after the 1999 disaster that affected both states: both countries’ citizens and media managed to spark joint disaster-related cooperation, easing tensions in their relations[6].

The key to an effective emergency response lies in the national, or local, actors and community-based response.

In the end, despite the difficulty states face in sharing power and resources, we live in an era that some see as the ‘end of Westphalia’. This does not imply, however, that states are obsolete when it comes to humanitarian affairs – on the contrary, they are one of the biggest pillars supporting it. However it risks becoming obsolete if it remains state-centric, as it was in the 20th century. With humanitarian politics increasingly becoming ubiquitous, the humanitarian space could become another arena for global confrontation. In this case, parting with some state powers (and responsibilities) and supporting non-state actors may not only suppress possible new conflicts, but could also make humanitarian assistance run more smoothly and more effectively – thus contributing to its original (state-centric) goal. The future of humanitarian assistance may not need further reform within the UN system or unification of all the coordination networks, but it will require all the actors involved to change their perspective and, in so doing, change the approach to humanitarian assistance.

[1] The idea had a positive agenda, though a rather poor implementation. For more on ‘disaster diplomacy’ see Kelman, Ilan. Disaster Diplomacy: How Disasters Affect Peace and Conflict. Routledge, 2011.

[2] See Nye, Joseph S. Jr. The Future of Power. PublicAffairs, 2011.

[3] See Naim, Moses. The End of Power: From Boardrooms to Battlefields and Churches to States, Why Being In Charge Isn’t What It Used to Be. Basic Books, 2013.

[4] Harvey P., Haver K., Harmer A., Stoddard A. ‘Humanitarian coordination in the Asia-Pacific region: Study in support of the 2010 OCHA Donor Support Group field mission’, Humanitarian Outcomes, 2010, p. 13

[5] For more on community-based humanitarian assistance see Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction, ed. By R. Shaw, Emerald, 2012

[6] On this issue see Ker-Lindsay (2000) ‘Greek-Turkish rapprochement: the impact of “disaster diplomacy”?’, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, XIV(1): 214-94

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |