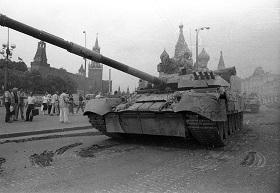

2022 is starting to look, sound, and feel an awful lot like 1962. If you wonder how 60 years could pass with so much historical change and so many global shifts to end up at something quite reminiscent of the peak point of the Cold War (the Cuban Missile Crisis), it is then necessary to go on a recent historical journey to offer an uncomfortable explanation as to how this has all come to pass: it is the fault of America’s Generation X.

Among the Generation X thinkers directing programs today, few are willing to open up for new political and diplomatic possibilities, encouraging new thinking about Russia in the 21st multipolar global century, not shackled to the mid-20th bipolar Cold War century. This does not bode well for the future of the American–Russian relations, nor is it good for the prospects of Russian Studies in the U.S. It certainly doesn’t bode well for diplomacy between the two countries, which is no small loss as everyone watches the events transpiring in Ukraine. Truly, this is about how the future gets defined. Right now, it is a future that looks depressingly familiar within a tightly framed intellectual past. It is a future shaped by the Lost Generation, who allowed itself to be swayed by immediate trends and pressures of job placement. Instead of focusing on who to blame or where to place shame, it is now critical to see institutions be the intellectual change the world needs more than ever. There can be no diplomatic revolution without it.

2022 is starting to look, sound, and feel an awful lot like 1962. If you wonder how 60 years could pass with so much historical change and so many global shifts to end up at something quite reminiscent of the peak point of the Cold War (the Cuban Missile Crisis), it is then necessary to go on a recent historical journey to offer an uncomfortable explanation as to how this has all come to pass: it is the fault of America’s Generation X. *

It is not exactly Generation X’s fault alone. However, given an unanticipated conflagration of unique historical and academic circumstances, the American scholarly landscape is surprisingly thin today when it comes to Russian Studies. The specific reasons for this might be somewhat surprising, which is something that is most certainly not openly discussed in various academic, professional, and diplomatic conferences. In fact, it is actively, if not aggressively, avoided. The dearth of American Generation X Russian experts is not because everyone somehow forgot Russia still existed after the end of the Cold War. Rather, what seems to have been forgotten is the undeniable uniqueness of the Russian history: some 1000 years of political and historical evidence notwithstanding, American graduate schools forgot in the 1990s that Russia would never allow itself to be politically irrelevant for long.

The West’s celebration of the Soviet Union’s dissolution and the so-called ‘end of history,’ the unequivocal victory of democracy over its main political system-rival, was accompanied by an almost unconscious Russian de-emphasis in prestigious American graduate schools. Yeltsin’s Russia was intellectually pushed aside by young aspiring scholars—after all, not only had it lost the Cold War, it also seemed to be mired in an inefficient kleptocracy, a political also-ran, a corrupt economic swamp, destined to remain a marginal player on the global stage in the 21st century. This impression was aligned in America with the demographic crisis Russia went through in the 1990s, with its overall population shrinking as opposed to growing, while the American academic/political communities dismissively shook their heads, feeling like the end of the Cold War quite possibly entail the literal end of Russia. So, by 1997, when many Gen Xers would naturally be advancing through their PhD programs, choosing dissertation committees and deciding on complex theses, they were subtly but decisively given an adamant piece of advice: abandon Russia.

Keep in mind: this advice was not petty. It was meant to be well-intentioned. By 1997-1998, to most in the West, Russia seemed as a place to study the problems of crime and corruption or a flawed democratic transition. This was everything the political Russia could be good for, from the perspective of the elite studying in American graduate schools. The mentoring of the next generation of experts, who were meant to take the leadership mantle from the Baby Boomers to lead the U.S. – Russia relations into the 21st century, stagnated and was stopped cold.

The not-so-subtle hint given to doctoral students was simple but powerful: if you truly want a job in academia and be engaged in ‘important’ work, Russia is yesterday’s news. If you want to be on the cutting edge, look to the Middle East and jump on the Islamist bandwagon. This is where the real scholarly action (and future job demand) was going to be. Of course, the seismic event of September 11, 2001, just a short three years later, stamped out whatever doubt remained amongst America’s now advanced Generation X PhD students. It was as if their mentors were prophets and had to be obeyed. And thus, the ultimate consequence that still limits the solving of Russian–American political problems today: the Lost Generation.

There are too few new thinkers or innovative minds that have emerged from Generation X when it comes to studying and understanding Russia, both politically and strategically. When examining and coding media sources and academic work, when viewing who mainstream media reaches out to for quotes and expert opinion, we will be hard-pressed to find a quote from anyone under 50 who is not massively dependent on the ‘Soviet presumption’ for explaining behavior. This is not an ‘ageist’ argument. The issue is not how old a person is—rather, it is the style of educational mentorship they were trained in. It is not by coincidence that virtually every single Russian foreign policy initiative today is characterized as a revanchist attempt to resurrect (symbolically or literally) the power and glory of the Soviet Union. It is not by an odd happenstance that Putin is exclusively evaluated in terms of the thirsty Soviet dictatorship.

Examine political reality today. Read as many sources of information possible. Whether it was the missile defense ‘shield’ in Poland and the Czech Republic, or Iran, or Syria, or the Sochi Olympic bombings, or Maidan, or Crimea, or the present special military operation around Kiev, what one sees are analyses that could have been cut from the New York Times in 1962 and just had the geographic key words altered. There is no imagination, no innovation, nothing evolutionary whatsoever. There has been no contrarian intellectual power transfer in America at all when it comes to understanding Russia. It is frozen in amber. Not surprisingly, the possibility for connection, collaboration, and dynamic negotiation is equally frozen.

Perhaps, worse than this diplomatic reality is the situation within think tanks, academic associations, institutes in the United States—all of them priding themselves on Russian expertise—to put it bluntly, there are negative career consequences for anyone interested in considering alternative ideas to the academic orthodoxy. Within Russian Studies, academic freedom is arguably under intense pressure so that there is only one acceptable kind of freedom. And that freedom is decidedly anti-Russian and deterministic. Complicating this, of course, was Russia’s stubborn unwillingness to remain irrelevant.

The little black box of Russian abandonment or anti-Russian indifference promoted by American academia over the past 25 years, now obliterated, means there is emerging a new generation of PhD students, once again intrigued, concerned, and fascinated by Russia. This new generation—a combination of Millennials, Y, and Z, all depending on how you define it—is now in or entering PhD programs. The concern, however, is that many of these programs are still run by either Baby Boomers on their last legs with an intense desire to see the old principles of the Cold War dominant once again or by a smattering of Generation X scholars, who have spent their entire careers under a domineering orthodoxy that has failed to evolve beyond the said Cold War. This leadership demands that the Cold War is the only political destiny allowed for Russia. Given the influence this community has on American policymakers, why is anyone surprised at the lack of evolution in the Russian–American relationship?

To pin things down, among the Generation X thinkers directing programs today, few are willing to open up for new political and diplomatic possibilities, encouraging new thinking about Russia in the 21st multipolar global century, not shackled to the mid-20th bipolar Cold War century. This does not bode well for the future of the American–Russian relations, nor is it good for the prospects of Russian Studies in the U.S. It certainly doesn’t bode well for diplomacy between the two countries, which is no small loss as everyone watches the events transpiring in Ukraine. Truly, this is about how the future gets defined. Right now, it is a future that looks depressingly familiar within a tightly framed intellectual past. It is a future shaped by the Lost Generation, who allowed itself to be swayed by immediate trends and pressures of job placement. Instead of focusing on who to blame or where to place shame, it is now critical to see institutions be the intellectual change the world needs more than ever. There can be no diplomatic revolution without it.

*This is an updated version of an article I wrote back in 2015. At the time, I thought it was crucially needed because of how poor the state of Russian-American relations was. I am sadly disappointed that it seems necessary for such an update seven years later, given that the relations arguably find themselves in an even worse condition.