Tensions in bilateral relations between Russia and the United States mean that Russia needs to adopt a position, and rather quickly, should official U.S. initiatives in nuclear weapons materialize during the remaining months of Barack Obama’s term in office. With this in mind, the available information on the potential nature of such initiatives should be analysed.

Off to a Good Start

As he began his term at the helm of the most powerful nation on the planet, President of the United States and Nobel Pease Prize winner Barack Obama shared his aspirations towards a world free of nuclear arms. Even though nuclear terrorism was singled out as the main threat at the end of the first decade of this century and the new U.S. administration was planning to focus on the safety of fissile materials, talks with Russia on a new strategic nuclear forces treaty reappeared on the agenda too. The general atmosphere of “reset” in U.S.–Russia relations was one of the key factors that led to the signing of the New START treaty, as both parties proved ready to compromise. For instance, the Americans adjusted their plans to deploy a missile defence system in Europe, something that Russia welcomed quite enthusiastically.

Yet missile defence has remained a hot topic and a stumbling block for “strategic” U.S.–Russia relations. It was during the treaty talks that efforts were first made to stipulate some sort of “legally binding” provisions on the subject, with a compromise eventually materializing in the “Statement of the Russian Federation Concerning Missile Defence.” According to this statement, a qualitative and quantitative build-up of U.S. missile defence capabilities that would create a threat for the Russian strategic nuclear potential is to be viewed as an exceptional circumstance threatening Russia’s supreme interests, which, under Paragraph 3 of Article XIV of the Treaty, would lead to its termination within three months’ (or any other stated period of time) notification of the other Party.

At the same time, the United States Senate passed a resolution following the ratification of the Treaty which, among other things, exempted the United States from any restrictions on the creation of missile defence systems and the development of long-range non-nuclear weapons, and stressed the need for upgrading the nuclear potential of the United States and holding negotiations with the Russian Federation on tactical nuclear weapons.

What is more, according to certain sources, the United States Congress debated spending $85 billion on nuclear weapons modernization over the next ten years, as well as the prospects for the new B61-12 nuclear bomb.

Revising the Legacy

In July 2016, reports appeared in the U.S. media about a series of executive actions contemplated by the Obama administration to advance the nuclear agenda during its final months in office. The proposed measures are both conceptual and technical, and they have already caused serious debates on both sides of the Atlantic.

The options include:

- Declaring a “no first use” policy for the United States’ nuclear arsenal.

- Preparing and adopting a UN Security Council resolution supporting a ban on the testing of nuclear weapons. This would be a way to formalize the commitment of the United States to not test weapons without first getting ratification from the Senate of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, which us very unlikely under current circumstances (and in the future).

- Offering Russia a five-year extension of the New START treaty (until 2026).

- Cancelling or delaying the development of the new Long-Range Stand-Off (LRSO) nuclear cruise missile.

- Removing the most deployed nuclear weapons from high (“hair trigger”) alert.

- Cutting back long-term plans for modernizing the United States’ nuclear arsenal (which will have reached $350 billion in the decade since the New START talks began, with the overall cost of the programme estimated at $1 trillion over three decades).

Fighting over the Legacy

The potential implementation of the “no first use” principle, combined with removing the nuclear weapons from “hair trigger” alert have led to heated debates. According to a number of experts, such steps would reduce the deterring effect of nuclear weapons and could provoke Russia and China to engage in a more aggressive foreign policy. Strangely, the continuing qualitative and quantitative advantage of the United States Armed Forces is ignored. It appears that, given the existing balance between military capabilities of the United States, Russia and China (in both conventional and nuclear weapons), an adjustment of U.S. conceptual approaches to the use of “Judgement Day weapons” would lead to a real military-political aggression against their allies.

At the same time, according to sources from The New York Times, the no-first-use pledge is likely to be taken off of the agenda – not least because of North Korea’s nuclear and missile programme, which gained serious momentum in 2016 and is “unnerving” Japan and South Korea. United States Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter points to the need to have the option of threatening a nuclear response in case of a non-nuclear (for example, biological) attack, while Secretary of State John Kerry suggested that allies of the United States could be tempted to obtain their own nuclear weapons if they perceived the U.S. nuclear umbrella as unreliable.

The initiative to extend the New START treaty can only be welcomed: perhaps at the current ratio of carriers and warheads, the treaty is still useful to Russia.

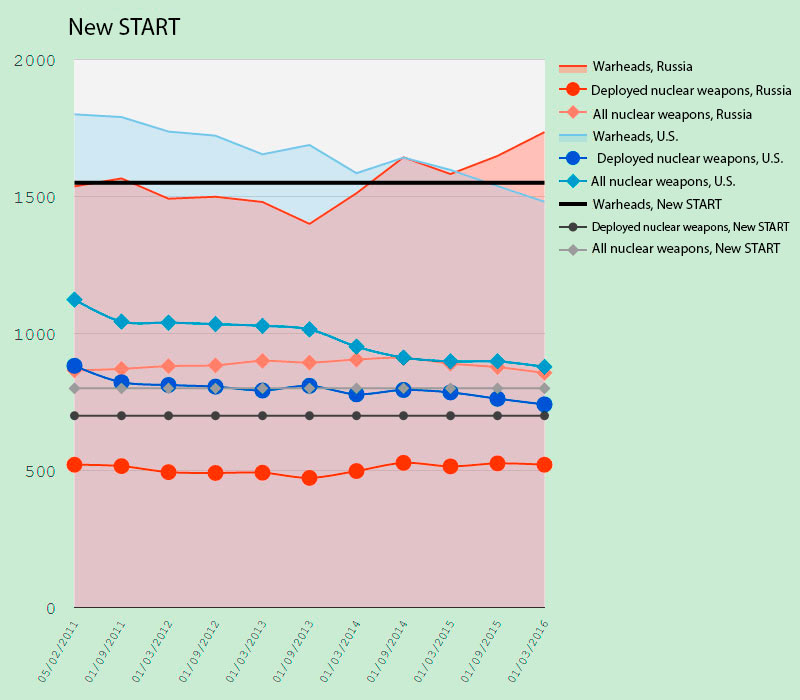

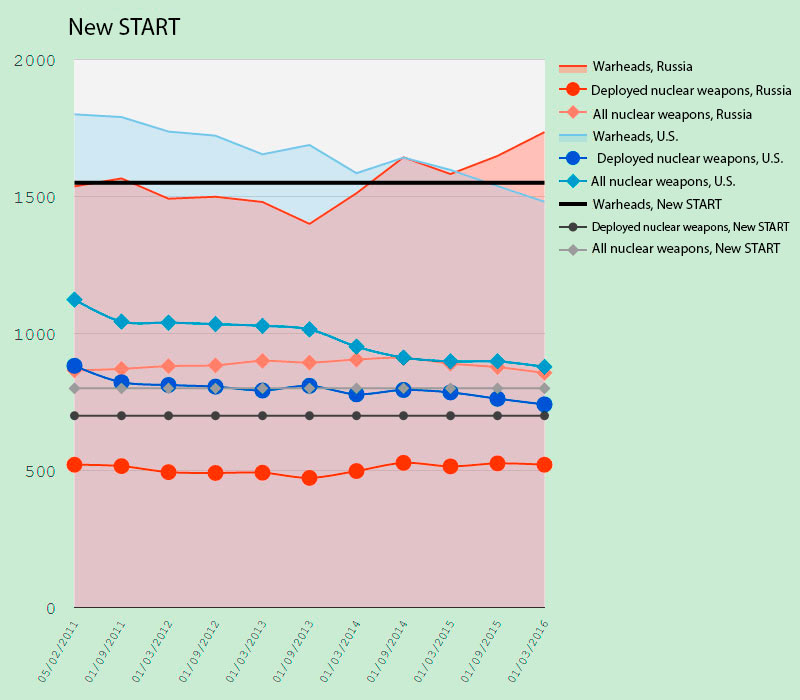

Figure 1. Russia and U.S. warhead and carrier ratio; illustration by the author based on U.S. Department of State data.

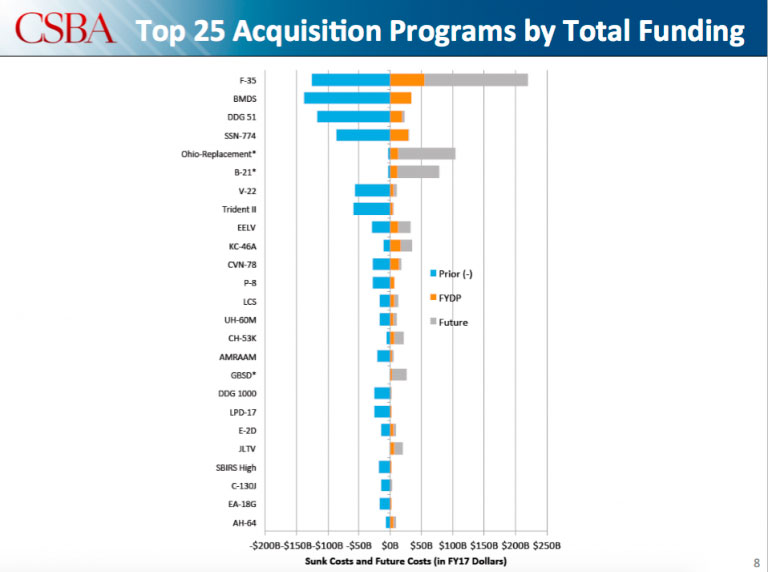

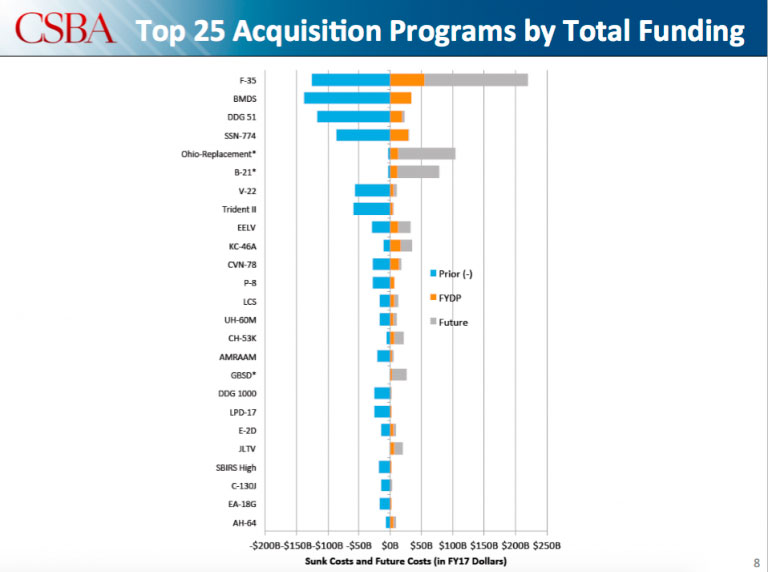

The projected modernization of the nuclear triad elements is among the top five most expensive programmes.

Figure 2. Twenty-five programmes by spending volume: blue – actual spending; orange – Future Year Defense Program (FYDP) allocations;grey– future estimates.

1. The SSBN Ohio replacement program for the U.S. Navy (it is so expensive that Congress has created a special fund to finance it)

2. The B-21 stealth bomber for the Air Force

…

5. A new intercontinental ballistic missile for the Air Force, the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD)

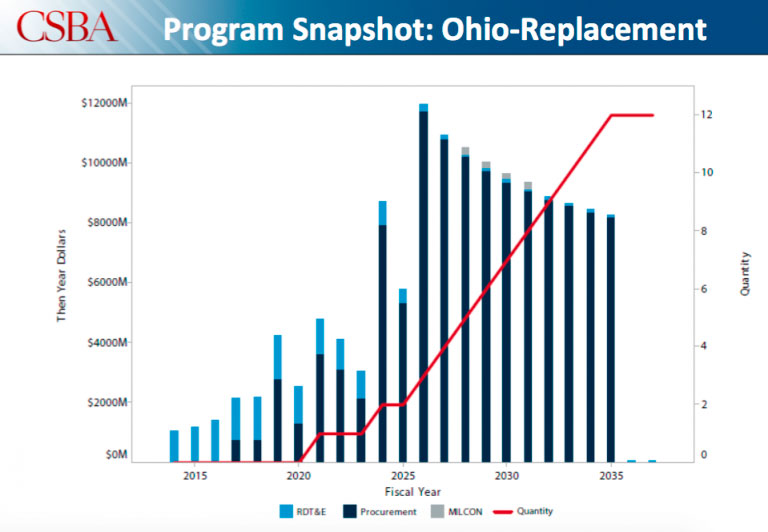

An even starker illustration of the bow wave effect (i.e. a substantial increase in spending on a weapons programme as it is being carried out) is available for the top entry of the list:

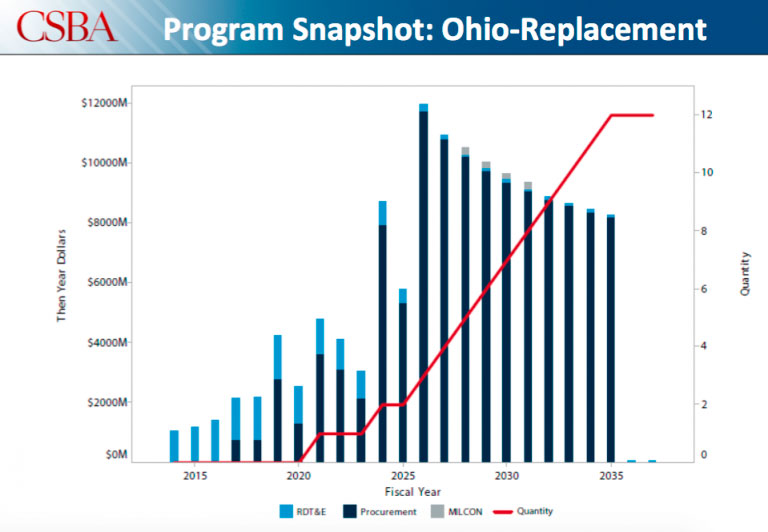

Figure 3. Estimated spending on the SSBN Ohio replacement, based on likely understated official estimates.

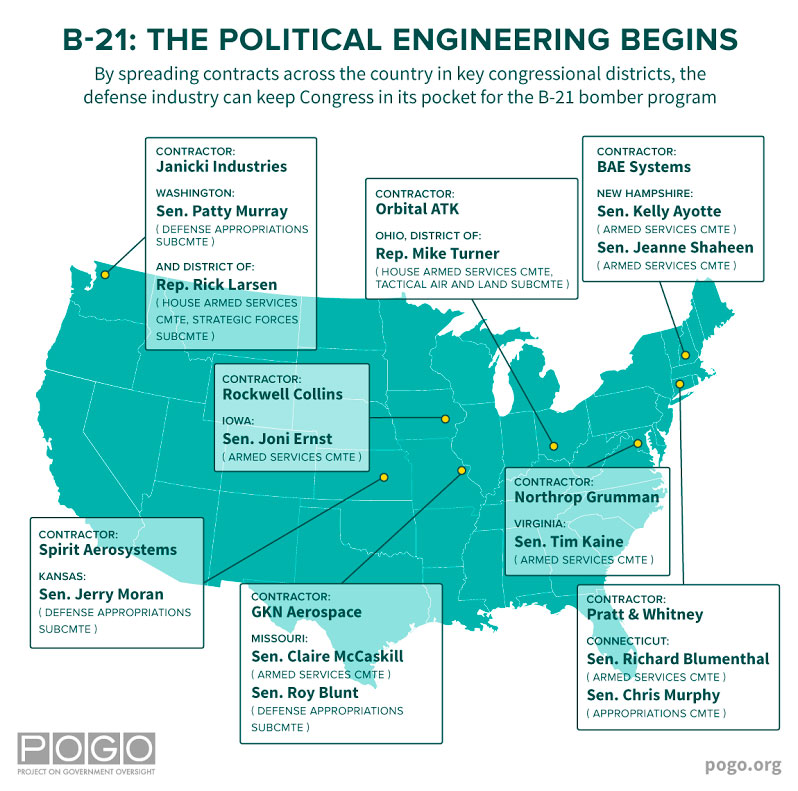

A serious discussion about the LRSO aircraft-launched cruise missile has been going on for a while now. Back in December 2015, a number of senators petitioned Barack Obama to cancel the development of the missile, for both economic and military-political reasons; in addition to the programme’s rather substantial cost ($20–30 billion for 1,000–1,100 missiles), the senators believe the above-mentioned B61-12 nuclear bomb, combined with the future B-21 bomber would make the missile redundant. Remarkably, the development of the B-21 has not been questioned (perhaps because of established cooperation involving companies from eight states, all with lobbying capabilities) and, moreover, its funding has been classified.

It must be noted that Russia has already adopted the new-generation Kh-101/Kh-102 aircraft-launched cruise missile. The proponents of LRSO development point this out too, as they emphasize the need for continued modernization of all the kinds of nuclear weapons that existed during the first nuclear century to guarantee deterrence of a potential adversary nowadays.

A revision of U.S. nuclear weapons modernization programs is quite possible and, under certain circumstances, inevitable. I believe that the Obama administration could play this card effectively and kill two birds with one stone by “patching up” the image of the United States as a leader of nuclear disarmament while optimizing its budget, e.g. by reallocating funding in favour of non-nuclear strategic weapons.

An article that appeared in The Washington Post revealed to the world the possible “nuclear” initiatives of the Obama administration, stressing a key problem related to their viability: by doing it unilaterally, without congressional buy-in, Obama risks launching policies that might not last much longer than the remaining months of his presidency. The “pendulum law” might well come into play after the change of guard at the White House, and nobody is insured against an increase in funding and a fast-tracking of “nuclear” projects, leading to the opposite of what is desired now.

The International Dimension

Seeking a UN Security Council resolution affirming a ban on the testing of nuclear weapons looks quite feasible and promising, yet several adverse effects should be mentioned. First of all, this would in fact establish a precedent for substituting a UN Security Council resolution for a legally binding international non-proliferation treaty the ratification of which has stalled. The matter of compliance with UN Security Council resolutions is generally related to the possibility of its enforcement, to which modern history abundantly bears witness. Admittedly, international treaties per se offer no panacea either, if the current state of the NPT is any indication.

On the other hand, the degree of attention paid by the United States to the UN Security Council’s opinion became evident during military campaigns in the former Yugoslavia and Iraq. A more than 20-year break in the production of new nuclear weapons combined with scientific and technological progress are good enough reasons to assume that there are motives for transitioning to a new generation of nuclear weapons. Modern technology makes it possible to simulate a wide variety of processes, yet it is doubtful that radically innovative weapons could be adopted without actual testing. As Hans M. Kristensen, Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, rightly pointed out, the story of the B61-12 in the context of a very serious scale of nuclear arsenal modernization programmes in the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom and China is jeopardizing the outlook for new breakthroughs in limiting the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Potential initiatives by Barack Obama as his term in office runs out can and must become the drivers for discussing this matter too, and ways to engage “third countries” in this conversation must be sought.

Russia’s Interests

Russia (if such negotiations do indeed begin, even in a traditional bilateral format) faces a difficult task: it needs to strike a careful balance between readiness to support the above-mentioned initiatives and counter-proposals on matters of more immediate interest. In particular, the “initiatives” completely ignore a number of “new” elements of modern strategic stability. While restrictions on U.S. missile defence are not on the agenda right now, given the launch of Aegis Ashore in Romania and the decision to deploy the THAAD in South Korea, it is possible to address the matters of non-nuclear strategic weapons (at least in the context of developing common terms and definitions) and the impact of cyber activities on strategic stability, and finally dot the i’s on endless mutual recriminations regarding medium- and short-range missiles.

A scenario of the United States asking Russia (and/or China) through official or unofffical channels to take similar measures “in exchange” for the implementation of some of its initiatives is also possible. In particular, I believe that a “no first use” adjustment of the U.S. nuclear strategy (if this matter remains on the agenda) could be linked to a clarification of the provision of the National Security Strategy of the Russian Federation on the conditions under which the use of nuclear weapons by Russia is considered possible.

At the same time, unrealistic preconditions should not be set; given the current crisis in U.S.–Russia relations, any interaction on international security is valuable in and of itself, and more so in such a sensitive area. Besides, the expiration of the New START treaty (even with a possible extension) is not that far off – ten years can fly by in the blink of an eye in today’s world – but a number of problems remain unchanged.