The exacerbation of tensions, mutual pressure and accusations have put a cornerstone Russia-U.S. agreement – the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty – on the brink of termination. The U.S. has accused Russia of deploying missile systems in grave violation of the Treaty, and a bill has been submitted to Congress that entails a de facto withdrawal from the Treaty.

The Starting Point

The Treaty Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Elimination of Their Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missiles (INF Treaty) concluded one of the major crises of the final stage of the Cold War, the decade-long crisis surrounding “Euromissiles” (1970s–1980s). The Treaty was signed on December 8, 1987, and called for eliminating cruise missiles and ballistic missiles with range between 500 and 5,500 kilometers.

For the first time during the Cold War, the parties agreed to eliminate entire classes of nuclear weapons that had been deployed in great numbers and had had a major significance for military planning.

Derailment

At the start of the century, the nearly forgotten INF Treaty again started showing up on the political agenda. Overall, the Treaty suited the U.S. as it did not apply to ship-based and air-launched missiles, the key component of U.S. striking power, but Russia expressed ever greater concerns. It was noted that in its current form the INF Treaty has long been an unfair arrangement since only the U.S. and Russia imposed self-restrictions, while such countries as North Korea, Iran, Pakistan, and India continue to develop these types of armaments. Vladimir Putin spoke about it specifically ten years ago in his famous Munich speech. Additionally, these new actors are close to Russia’s borders.

The issue of China has been and remains a crucial one. China is the world’s undisputed leader in the missiles of INF-prohibited classes — its weapons include IRBM of DF-21 class and DF-26 class and land-based mobile missile systems (LBMMS) with DF-10 cruise missiles. With DF-26 systems deployed in western China, their range covers the greater part of Russia’s European territory.

There were also INF-related grievances against the U.S., for instance, in connection with target missiles used for tests of the U.S. missile shield and concerning the system’s components deployed in Europe. Russia regularly states that such targets as, for instance, Hera constitute at least IRBM prototypes, if not actual IRBMs. In such cases, the U.S. uses loopholes in the INF Treaty, which allow for developing target missiles. However, work on target missiles and R&D conducted in the 2000s on ship-based solid-fuel IRBMs led to Moscow’s well-founded concerns since they can serve as a basis for creating “neo-Pershing” missiles.

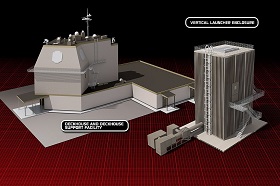

However, when the Obama administration switched to the so-called “adaptive approach” to the European missile shield, it became a true gift to those searching for grounds to accuse the U.S. of violating the INF Treaty. Instead of launchers for GBI interceptor missiles which, first, had greater potential and, second, were not covered by the INF Treaty, the U.S. deployed land-based derivatives of ship-based Aegis systems (Aegis Ashore) in Poland with light RIM-161 SM-3 interceptor missiles. This is a simple and cheap solution, but the devil is in the details: SM-3 uses the same Mk. 41 launchers as Tomahawk cruise missiles.

However, the current exacerbation in bilateral relations occurred because of grievances the U.S. has against Russia. Traditionally, these grievances are related to RS-26 Yars-M and cruise missiles that were part of the Iskander-M modular system. The former have been and still are criticized for allegedly being essentially Pioneer 2.0, however, according to the INF Treaty, a missile’s range is the maximum range demonstrated during testing, and in May 2012, a missile was sent for approximately 5,800 kilometers. The deployment of RS-26 has been postponed several times; perhaps it was due to purely technical reasons, but political reasons cannot be discounted either.

The situation with the Iskander-M system cruise missiles is more complex. The range of the R-500/9M728 missiles deployed operationally since 2013 is stated at 500 kilometers. It is believed that they are developed on the basis of the Relief system missiles; the Relief system was eliminated under the INF Treaty and had a range of approximately 2,600-2,900 kilometers. However, the R-500 is equipped with a non-nuclear (and consequently, significantly heavier) warhead and it is 1.5 meters shorter, which means a much smaller fuel supply and range. Yet it was another missile, 9M729 (NATO reporting name: SSC-8), that was the real troublemaker. The only thing known for certain about it is that it exists.

It is traditionally believed that the 9M729 is a land-based derivative of the ship-based Kalibr system’s 3M-14 cruise missile. It is longer than the R-500; consequently, the LBMMS had to be extended by a meter or two. Since 3M-14 have a range of up to 2,600 kilometers (the range they demonstrated in the Syrian war was clearly greater than 1,000 kilometers), the concerns of the U.S. are understandable.

Nevertheless, until recently, the system had been tested and was of interest to a narrow circle of experts only. Everything changed on February 14, when an article appeared in the New York Times. In short, the article claimed that back in the end of 2016, Russia had deployed two battalions with 9M729 cruise missiles, with four LBMMS per battalion: one test battalion in Kapustin Yar and another one “in central Russia.”

Interest in the subject surged again on March 8, at hearings in the House Armed Services Committee, when Gen. Paul Selva, the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in response to a question from a congressman confirmed that Russia had deployed a cruise missile system “that violates the spirit and intent of the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty.”

However, the most troubling development in the current exacerbation of relations occurred on February 16 (only two days after the publication of the article in the New York Times), when a group of Republicans submitted both to the House and the Senate the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty Preservation Act intended to force Russia to comply with the treaty:

— to state that the U.S. is suspending the INF Treaty until Russia complies with it again;

— to start R&D on an American LBMMS with an intermediate-range cruise missile that can carry both nuclear and conventional warheads (apparently, some kind of Gryphon 2.0 with Tomahawks) and to start testing within a year. Subsequently, these systems will be supplied to the allies of the U.S.;

— to actively seek ways to enhance air and missile defense in Europe;

— to analyze in detail whether RS-26 ICBM are covered by START-3 or violate the INF Treaty;

— to not extend START-3 and to bar Russia from flying over U.S. territory under the “Open Skies” Agreement until Russia complies with the INF Treaty.

It goes without saying that if the bill is passed the INF Treaty will have failed completely, and unlike in the 1980s, the U.S. plans to supply other countries with such systems. At the time of writing, the bill is under consideration in the appropriate committees in both the House and the Senate.

The End or a New Beginning?

What prospects does the INF Treaty have? There are a great number of options, but they can be boiled down to three scenarios: best case, neutral, and worst case.

The best-case scenarios involve the INF Treaty being preserved in full. This is possible after a mutual pullback following rapprochement between the security stances of Moscow and the new U.S. administration. For instance, a trade-off is possible: Russia abolishes its plans to deploy land-based mobile missile systems with cruise missiles in exchange for major limitations on the missile shield in Europe — it is possible that the LBMMS are being created for this very purpose, and this is an ideal scenario for Russia.

Ballistic attack systems could also be abandoned if NATO reduces its overall military infrastructure close to Russia’s borders and if it proves possible to return to the trends seen at the start of the decade, when American forces were slowly withdrawing from the continent. It is the best option: mutual security would be enhanced and spending on arms races would be avoided; however, it is the least feasible, too. Donald Trump’s administration is already accused of being “pro-Russian,” and it will have to make visible concessions to Moscow, while Moscow will formally do nothing: in short, Russia strictly adheres to the Treaty as things stand. On the other hand, Russia will not make any unilateral concessions either; even pressure similar to the 1979 “Double-Track Decision” would have little effect: the U.S. does not have intermediate-range ballistic missiles, and developing them would take years, while land-based cruise missiles would not drastically change the situation. Neutral scenarios are those which entail introducing new rules of the game, some kind of an INF Treaty 2.0 signed officially, or, like the “Presidential Nuclear Initiatives”, announced overtly or covertly and executed as a mutually beneficial agreement.

For instance, restrictions may be left in place for ballistic missiles only as the most dangerous ones since they can be used to launch a decapitation strike. It might be useful to negotiate an additional ban on equipping them with nuclear warheads and the establishment of mutual inspections; this way, a tactical nuclear weapons race would not be instigated, and the overall heated response of the media and the political circles could be deescalated. Relations between Russia and the West are now such that it is hard to hope that the parties would “pull back,” yet there could be hope for drawing new, mutually acceptable “red lines.”

Worst-case scenarios are particularly pessimistic and entail the complete termination of the INF Treaty with mutual grievances. The parties would put the responsibility on each other and claim that in response they have been forced to develop systems that are fully in violation of the old Treaty, including IRBMs, even if it takes years. This option is extremely dangerous as it may spur another arms race. For Russia, an arms race is particularly sensitive because, as in the 1980s, it is geographically far more dangerous for Russia than for the U.S. A serious increase in military spending or re-channeling funding from conventional weapons to nuclear ones would also be unacceptable since it would deliver a blow to the economy, which requires modernization, or to the efficiency of the military in local conflicts. The parties should make every effort to avoid this scenario since it is a lose-lose for everyone.

Accusations against Russia that have been spiraling out in the world media over the last few months are grounds for concern that we are leaning toward the third option; however, after the start of a dialogue with the new U.S. administration, there is hope for a positive outcome.